The second year of the Adams administration had a lot of new lows for the street safety movement, as the mayor dispelled notions that he would follow legal requirements to build out miles of bike and bus lanes each year. If that wasn’t enough, Hizzoner’s cronies actively thwarted DOT’s work to build safer streets, at the service of powerful interests.

Meanwhile, the Council bungled the historic pandemic outdoor dining program, rendering it part-time, and both parts of city government dropped the ball on one of the few mechanisms to hold the most reckless drivers accountable.

There is plenty to choose from, but what is the biggest failure of 2023?

The nominees are...

Vision Zero backsliding

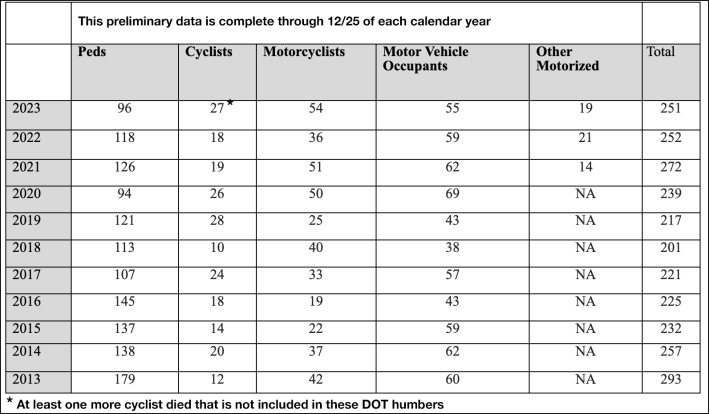

This year is on pace to be among the worst for traffic deaths since former Mayor Bill de Blasio launched the Vision Zero program in 2014 with a goal of eventually reaching zero fatal crashes.

DOT has touted a decline in pedestrian fatalities against the backdrop of rising numbers nationally, but there were 251 overall road fatalities in the five boroughs, just shy of the 252 in 2022, according to the latest data through Dec. 25. Ninety-six of those were pedestrians and cyclist deaths soared to 28 this year, the second-highest tally in a decade.

There were a whopping 93,353 injuries from crashes through Dec. 24, and those numbers are also up almost across the board, with the exception of pedestrians, where they were flat compared to last year, according to the NYPD.

Behind the carnage of some 260 people injured in crashes per day were particularly terrible, but preventable, tragedies.

A horrific case early on in the year was when a driver hit and killed 7-year-old Dolma Naadhun at a street corner where cars blocked visibility in Astoria in February, or the NYPD tow truck driver who struck Kamari Hughes, also 7, at a Fort Greene intersection in October.

The children’s deaths galvanized a grass-roots movement by advocates and community boards urging the city to opt into state law banning parking within 20 feet of a crosswalk — a well-established street safety design known as “daylighting” that New York City has long opted out of in favor of more private car storage.

BQE blues

The quagmire of what to do with the crumbling Brooklyn-Queens Expressway shifted into reverse this year and brought back some of the greatest hits of highway follies, as city and state officials failed to undo the harms of the Robert Moses-era road that has been dividing neighborhoods for half a century.

The Adams administration revived the spirit of the master planner by seeking ways (and a lot of money) to rebuild and expand the BQE on the city-owned triple-cantilever portion in Brooklyn Heights, while Gov. Hochul, who controls most of the interstate road, has remained largely absent from the discussions to reimagine the highway.

Brooklyn political power brokers also secretly pushed for the 21st-century highway expansion in closed-door meetings with City Hall, despite all elected officials representing the corridor opposing a bigger roadway, and amid concerns that the project would intrude on Brooklyn Bridge Park.

The city justified its highway re-widening project saying it would bring the old road up to modern federal standards — unlocking grant money from Washington, D.C. — while claiming that the narrowing of the cantilever to two lanes under the de Blasio administration two years ago has since led to spillover traffic in nearby neighborhoods.

But the same city officials ignored nearly four-year-old recommendations by a BQE expert panel to restrict access to on ramps to manage congestion, such as the hot mess that is the Atlantic Avenue interchange, and local groups the city worked with for community feedback accused officials of advancing “predetermined” plans to keep the highway for generations more.

A rogue City Hall

Speaking of power brokers, Adams and his surrogates made an art out of derailing street safety projects this year, and chiefly among the City Hall saboteurs was the mayor’s chief adviser and enforcer Ingrid Lewis-Martin.

The administration established the playbook of interference with a rogue chain of command led by non-transportation bureaucrat Richard Bearak whom they dispatched to review and impede efforts to build out better bike and pedestrian infrastructure.

The insiders first blocked and then watered down DOT’s much-needed road diet for the deadly McGuinness Boulevard in Greenpoint, bowing to the powerful Argento family, which runs the film studio company Broadway Stages in the north Brooklyn area and has been a major political donor of the Brooklyn Democratic machine.

The city continued backpedaling on key projects like the Fordham Road bus upgrades in the Bronx, where Adams backed off plans to speed up commutes for 85,000 daily bus riders, caving to pols like Council Member Oswald Feliz and U.S. Rep. Adriano Espaillat, along with influential business interests like the Belmont Business Improvement District Chairman Peter Madonia, Fordham University, Monroe College, St. Barnabas Hospital and even the New York Botanical Garden and the Bronx Zoo.

Back in Brooklyn, DOT abandoned parts of projects in the 11th hour, like on Ashland Place, where developer Two Trees successfully lobbied against the two-way bike lane on the block outside its building, or on Underhill Avenue, where the nearly-done Underhill Avenue bike boulevard stalled and could be next on the chopping block.

Failure of the Streets Plan

Adams’s constant undercutting of his own agency also undermined any hope of his administration meeting the legal minimums under the Streets Master Plan, which mandates building 30 miles of new bus lanes and 50 miles of new protected bike lanes this year. The mayor is falling short of the required benchmarks for the second year of his tenure.

The mayor made it clear he didn’t care about following those requirements when he told DOT workers during a bizarre speech at the agency’s headquarters that his legacy would not be how many miles of bike and bus lanes he achieved, but that New Yorkers “on the ground” felt "heard" by the mayor.

The four-year-old Streets Plan law and its annual mileage minimums was supposed to move beyond the city’s “piecemeal way we plan our streets,” then-Council Speaker Corey Johnson said at the time, but Adams has chosen the opposite tack, promising to literally go door to door to collect community feedback on just one project.

Death of DVAP

The city’s Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program, or DVAP, sunsetted this year, ending a failed, three-year experiment to hold the city’s worst-of-the-worst drivers accountable that was deeply flawed from the get-go.

Neither Mayor Adams nor the City Council showed interest in continuing the pilot that allowed the city to order motorists take a safe-driving course if they'd been caught on camera with 15 speed- or five red-light camera violations in a year.

This first and only measure to hold motorists accountable for automated tickets beyond just paying a fine came about after advocates rallied elected officials into action after a horrific 2018 crash in Park Slope.

Motorist Dorothy Bruns — whose car had been tagged several times for speeding in school zones and running reds — blew a red light and fatally struck and killed two children, injured their mothers, including one of them who was 39 weeks pregnant and lost her unborn child as a result of the injuries.

The Council created DVAP in 2020, but legislators watered down the bill from seizing vehicles of reckless drivers caught on camera to simply giving DOT the ability to order them to take a safety course.

The agency only mailed out about 1,600 notices to drivers, about half of whom took the course, and only seized 12 vehicles over two-and-a-half years of the program.

Truncated outdoor dining

The Council passed a permanent outdoor dining program in August after 18 months of largely secret negotiations for how to replace the three-year temporary pandemic-era "restaurant shed" rules, but city lawmakers bowed to the parking class by restricting streeteries in the roadway to eight months out of the year, reverting to car storage over the winter, while sidewalk seating can remain year-round.

The Covid-era program repurposed a historic amount of curb space for al fresco dining structures at a time when indoor dining was banned or limited to prevent the spread of the deadly virus. The simplicity of the regulations allowed outdoor seating setupts to grow 12-fold compared to the more restrictive pre-pandemic regulations, and spread to more than a dozen areas that never had the outside cafés.

Restaurant owners and livable streets advocates begged the legislators to keep an all-year option for the curbside structures, and allow some of the more elaborate setups for which businesses shelled out tens of thousands of dollars to remain standing.

A Crowded Queensboro Bridge

Another de Blasio promise, giving pedestrians a separate path from cyclists on the crowded Queensboro Bridge, suffered setbacks this year, with DOT pushing the latest opening date to “mid-2024” to repurpose the south outer roadway for people on foot.

The change was originally supposed to happen by the end of 2022, but the city has continued to force pedestrians and bikers to share the dangerously-narrow north outer roadway amid soaring numbers of cyclists crossing the overpass.

Why the delay? DOT claims it needs to keep the southern shoulder lane open for cars to avoid causing traffic backups in Manhattan during road closures amid the rehabilitation work on the span. But the agency's own stats revealed taking one more lane for pedestrians would cause a mere 5 percent more vehicles queueing to go to Queens.

Meanwhile, people are being hurt in crashes as cyclists and pedestrians in both directions share a single lane.

‘Mountable’ bike lanes

One of the most misguided street designs in recent memory is the raised curb bike lanes DOT has installed in three boroughs, which are blocked so chronically by parked cars they’re basically useless and even the agency labels them “mountable”!

The recently completed mountable lanes on Grand Concourse in the Bronx are a perfect example, where the city spent $62.5 million over three years to tear up the road and install the bike paths on 1.2 miles of the service roads — only for motorists to hog the new space from day one.

Officials also installed the flawed design in Greenpoint and in the Rockaways, and the results were predictably the same.

Nevertheless, DOT plans to pour $24 million in federal grant money to install yet more mountable paths on Queens Boulevard next year — albeit raised 50 percent higher — arguing the design works better for emergency services to still get around on the car lane next to the bike paths.

Those are the nominees. But now it's time to vote. (If you don't see a poll below, refresh the page):