It's fourth down — and the Adams administration will punt to the state.

The city's Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program — a tool to rein in drivers who accrued 15 camera-issued speeding tickets in a year — expires on Thursday. And the Adams administration and the City Council have no replacement policy or new strategy to deal with the worst of the worst recidivists, except to appeal to the state for new laws.

And neither party even pretends otherwise.

In a brief exchange on Tuesday, Mayor Adams confessed that he didn't know the three-year-old law was about to expire. Then, Deputy Mayor Meera Joshi confirmed that the city has no plan beyond hoping state lawmakers help out.

"We will look to the advocacy world for support to go to the state and get better restrictions and better enforcement tools ... on the registrations and licenses of those who repeatedly run red lights [and] repeatedly get speed camera violations," she said. "We need sharper tools."

Earlier in the month, Council Speaker Adrienne Adams also expressed no urgency — or plan — for the demise of the law on Oct. 26.

"As we consider possibilities going forward," she said on Oct. 5, "we are going to take a look at next steps."

Adding to the concern over the elimination of the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program is the silence of the city's political class: The Department of Transportation, the Department of Finance, the Sheriff's Department, the chair of the Council's Transportation Committee and the NYPD all declined multiple requests — in person and via email — to discuss the demise of the program.

"The program launched with a simple idea of getting reckless drivers vehicle off our streets, so it's incredibly frustrating and disappointing that we're in this situation," said Elizabeth Adams, the deputy executive director for Public Affairs at Transportation Alternatives.

The street-safety group wanted the Council to reauthorize and strengthen the program, but did not persuade Speaker Adams before tomorrow's sunset.

First, what happened here?

The Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program was a failure before the ink had dried on it in early 2020. No wonder it failed: When then-Council Member Brad Lander proposed it two years earlier, the idea was to have the city impound vehicles that had been caught on camera five times for either speeding or running a red light within a 12-month period.

The de Blasio administration negotiated a watered-down bill: After 15 speed-camera tickets or five red-light tickets, the driver could — could — be required to take a 90-minute safety course.

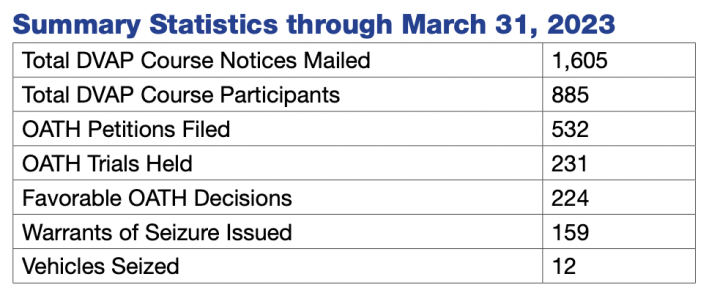

In the two-and-a-half years between the program went into effect on Oct. 26, 2020 and March 31, 2023, when the DOT assessed it, only 885 people took the course — out of tens of thousands of people who had accrued 15 or more camera-issued speeding tickets in any 12-month period. Only 12 vehicles were ever seized, either from the 720 drivers who failed to take the course or from many drivers (the number is not known) who reoffended.

The DOT's half-hearted approach to the program — which was small in scale as a result of limited resources — was clear in its own report on the program's failure.

"The vehicles of people who took the DVAP course … showed new violations that their previous records did not predict," the agency said. "DVAP course participation did not prevent these new violations from occurring."

Plus, the agency never saw the program as a way of preventing bad drivers from driving, but merely as a re-education tool.

"The intention of DVAP is not to prevent dangerous drivers from using their vehicles," the DOT summation report continued. "It is to compel those drivers to take a safety course by threatening vehicle seizure if they fail to do so."

OK, so where are we?

Starting on Thursday, if a speeding driver is nabbed for the 15th time in a 12-month period, all he or she will have to do is pay the $50 ticket to avoid any scrutiny from officials who have promised to keep our roads safe. That person can, in fact, speed every day — even multiple times per day — and as long as the $50 tickets are paid, that person is a driver with a pristine record as far as city and state officials, insurance companies and district attorneys are concerned.

So how can political and appointed leaders keep people safe from these recidivist predators? There are surprisingly few tools — and a surprisingly few members of the political elite fighting to change that. Sheriff Anthony Miranda didn't want to talk about it. Nor did Council Transportation Committee Chair Selvena Brooks-Powers. Nor did any official with the departments of Transportation or Finance. And the NYPD has a new Transportation Bureau chief whose spokesperson said he'd be glad to talk about reining in reckless drivers ... until he suddenly wasn't.

As such, we have no idea what public officials are thinking beyond a few facts that Streetsblog was able to cajole from city data and agency spokespeople:

The car of a reckless driver can be disabled with a boot or towed away if its owner has more than $350 in unpaid, adjudicated tickets. And the sheriff has been stepping up its effort to get those scofflaws off the streets (see chart below):

But it's only temporary: drivers get their cars back when they pay the tickets or enter into a payment plan. And the tranche of towed scofflaws includes the reckless and the simply impoverished. There's no way of knowing how many of those towed cars belonged to recidivist speeders who didn't pay their tickets or to illegal parkers who also thumbed their nose at the Department of Finance. But the chart above no doubt includes lots more illegal parkers than speeders, given that parking tickets are more expensive than the $50 camera-issued tickets for reckless driving in school zones.

A reminder of the shortcomings of New York City's ability to use towing to keep reckless drivers off the road came after repeatedly sanctioned driver Tyrik Mott killed 3-month-old Apolline Mong-Guillemin and critically wounded her mother on a Fort Greene street in 2021. As Streetsblog reported at the time, Mott's license had been suspended, and he had far more unpaid tickets than the $350 threshold, but his car was never towed (he may have parked it off-street).

But his car was in public plenty of times: during one period, he got at least nine tickets for such transgressions as blocking a hydrant or parking in a bus lane — tickets written by humans who could have gotten the car disabled had they connected the dots.

So what's next?

As unbecoming as it is for local officials to claim they are powerless to solve a problem on their local streets, Joshi is right that additional lawmaking in Albany will be a key factor of the equation.

And many bills are pending, including reauthorizing — and expanding — the city's red-light cameras, which only cover 150 intersections right now, but could increase 10-fold.

Relying on Albany, however, has proven to be frustrating. In the session that ended in June, the state Assembly failed to even allow New York City to set its own speed limit, a particularly low-hanging fruit. In that same legislative period, lawmakers failed to require complete streets designs; failed to pass a bill to suspend the registration of any car caught by a speed camera five times in any 12-month period; failed to make it easier to suspend a learner’s permit; failed to ban the relicensing of drivers who have been twice convicted of road violations that caused injury or death; failed to allow speed camera fines to escalate upon repeat offenses.

And in the previous session, the legislature failed to make camera tickets subject to points on a driver's license and failed to pass a provision to report speed camera violations to a driver's insurance company.

Such failures haunt state Sen. Andrew Gounardes, whose name was on most, if not all, of the above bills.

Sit with Gounardes over a coffee in Bay Ridge, and he'll talk for as long as you want about efforts to get reckless drivers off the road. He says he uses a "try everything" approach. When his punishment approach of increasing the price of tickets was called a money grab, he tried a "market" approach: proposing to tell insurance companies when their customers are reckless, so that the companies will re-price the increasing risk.

"I don't think people were ready for that step, logically," he said. "But I'm not giving up on that idea."

He's also tried to lower the threshold for having a driver's license or vehicle registration suspended — but the problem is, people who follow the rules would abide by the suspension. But rule-followers are not the ones who are getting their licenses suspended in the first place. Rule-breakers — who are — keep breaking the rules ... and keep driving on suspended licenses. (And, he said, they violate the speed limit whether it is 30, 25 or 20.)

So Gounardes is onto his next effort: technology to do the job that the cops and the sheriff and the Department of Motor Vehicles has failed to do.

"OK, we won't take your license. We won't take your vehicle. But we're going to physically force you to slow down," he said, referring to his new bill to require repeat offenders to have a speed governor installed or deployed on their car.

Gounardes said his Albany colleagues raised reasonable objections to prior bills, but this one could only be opposed by someone who believes, "I have a right to speed."

"But that's an objection that just has no credibility," he said.

If any of these bills are going to succeed, it will take a shift in approaches, if not basic semantics, because most drivers hear, "We want to stop you from driving" whenever accountability is sought for reckless or killer drivers, he said.

"The conversation needs to be like, 'What do we do about people who break the rules, just like we do in any other area?'" he said. "I think the strategy is to separate those two questions: we're not trying to make it impossible for you to drive. We're just trying to stop the worst drivers. The speed governor bill will end up applying to the worst 4 percent of drivers. By focusing on the worst of the worst, we hope to create more space for people to entertain more aggressive and creative enforcement opportunities than just the gotcha ticket."

Speaking of creative opportunities, Gounardes has also introduced a bill that would change the state's environmental review process so that it would not concern itself with the resulting level of service for drivers, but would require projects to reduce the amount of driving the project would create.

Less driving will mean less reckless driving.

Also on the state level, the Department of Motor Vehicles has proposed increasing license points for some reckless driving offenses that weren't even previously subject to points, as Streetsblog reported.

The agency declined to discuss how to physically prevent drivers with suspended licenses or registrations from continuing to drive.

Local efforts are small

The criminal justice system also has a role to play, but there's only so much local prosecutors to stop a reckless driver, given that they're called in after the recklessness.

Two years ago, Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez started collaborating with the Center for Justice Innovation on "Circles for Safe Streets," which uses a non-carceral, restorative justice model to show reckless drivers the impact of their dangerous habit.

The idea is to bring together drivers who have killed or injured someone with one of their victims or a victim's family member for a visceral session. Afterwards, the driver must write a one-page reflection on how the session will prevent them from committing further harm with a deadly vehicle.

But the program is limited: For one thing, many defense lawyers don't want their clients to participate because admitting guilt in a criminal trial comes back to haunt them in a civil case.

Still, the Brooklyn DA's office hopes to expand the program. And the offices of other district attorneys said they either have or hope to have such a program.

But then again, one of the main failures of the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program — which created a safety course for repeatedly reckless drivers — was that the city never could establish that such a course really works.

"There were still many vehicles belonging to DVAP course participants that continued to accrue speed- and red-light camera violations [after the course], including some that even increased their frequency," the agency's report said.

So it's back to the drawing board. But which one?