Abate this abatement program.

The Department of Transportation wants the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program to simply expire in part because it did not dramatically improve safety among the worst-of-the-worst drivers and led to only a tiny number of vehicle seizures — but also because of legal challenges and limited ambition of the program in the first place.

"Overall, given the uncertain effects of the program, its high cost per participant, and the complexity of its implementation, DOT recommends DVAP should not continue after the end of the pilot" on Oct. 26, 2023, the agency said in its long-awaited (and legally late) report issued on Friday.

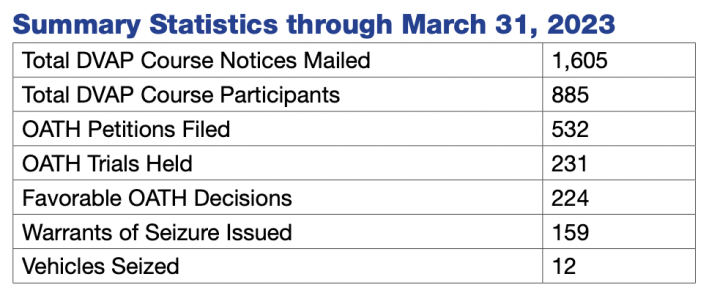

DOT avoided taking blame for the shortcomings of the program, which was introduced in the Council in 2018 and passed in 2020 after being watered-down by the de Blasio administration. Instead of seizing vehicles of drivers caught on camera with 15 speed- or five red-light camera violations in a year, the final law simply gave DOT the ability to order these very worst drivers to take a safety course — a power that DOT did not exercise much at all, based on the agency's own numbers between the beginning of the program on Oct. 26, 2020 and March 31, 2023:

And for that, City Comptroller Brad Lander, who drafted the bill that created the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program when he was in the Council, blamed DOT squarely. A program that reaches a tiny fraction of the tens of thousands of drivers with egregious records is a failure.

“DOT’s slow and limited implementation of DVAP set the program up for failure from the very beginning," Lander said in a statement on Friday. "We should not eliminate the one tool we have to hold accountable drivers who repeatedly violate traffic safety laws – but instead should be reauthorizing and strengthening DVAP as part of a broader, more ambitious program to address the plague of dangerous driving." (In anticipating of the report's release, Streetsblog asked DOT to make key officials available for comment, but agency spokesman Nick Benson said, "We respectfully decline.")

Overall findings

According to the report, only 885 drivers took the 90-minute in-person safety course through March 31, 2023. — and those participants did reduce their overall number of violations by 55 percent.

The problem: A control group of reckless drivers that did not take the DVAP course reduced its violations by 37 percent.

"There were still many vehicles belonging to DVAP course participants that continued to accrue speed- and red-light camera violations in excess of the DVAP qualification threshold, including some that even increased their frequency," the report said. "The difference in the rates of violation reduction between the program and control groups cannot be definitively attributed to the DVAP class. ... The history of the New York City speed and red light camera programs has been that violations generally fall over time."

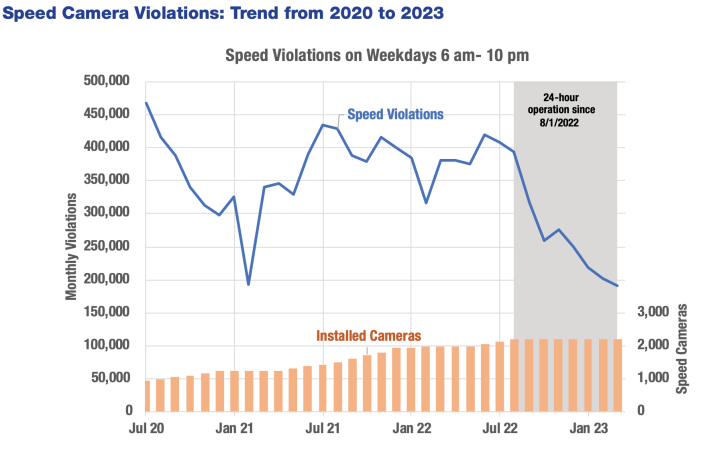

Indeed, camera violations have been dropping even as more cameras have been installed and their hours of operation have increased. That's a function of how few drivers get a second ticket after the shock of getting the first one, the agency has said.

The DVAP numbers break down differently by how closely DOT monitored the participants:

A group of 88 people whose driving was evaluated for a full year after taking the course went from an average of a truly horrifying 35 speed-camera and 1.2 red-light camera tickets per person per year to a still-truly horrifying 15 speed-camera and 1.3 red-light camera tickets per person per year after taking the course.

Meanwhile, that cohort's control group changed from an average of 32 speed camera tickets and two red lights tickets per person to 19 speed camera tickets and 2.6 red light tickets.

A larger group of drivers who were evaluated after only six months showed larger declines in violations per person in both speed- and red-light camera tickets after taking the course, but in those six months, the drivers ended the DVAP course still exceeding the DVAP course threshold of 15 speed-camera tickets per year.

In other words, if they took the course, they were still likely, on average, to hit a level of recklessness that ... triggers the course.

And DOT admitted that the safety course appears to be useless to reduce red-light violations.

"The vehicles of people who took the DVAP course ... showed new violations that their previous records did not predict," the agency said. "DVAP course participation did not prevent these new violations from occurring."

The problem with DVAP

Perhaps the biggest problem with the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program is that — at least in its final, passed form after negotiations with then-ruling de Blasio administration — it does not really even aim to get reckless drivers out of their cars.

"The intention of DVAP is not to prevent dangerous drivers from using their vehicles," the DOT wrote in its summation report. "It is to compel those drivers to take a safety course by threatening vehicle seizure if they fail to do so."

Another reason why DOT considers the program a failure? Its success can't really be judged: More than half of the program participants couldn't even be evaluated due to swapping out their plates, moving away, or the report being drafted before DOT could know if scores of drivers had reoffended.

It's also, allegedly, expensive to administer, the DOT said, though its argument was somewhat contradictory.

"The agency dedicated significant staff and financial resources to the program," the report stated, though it also claimed that "legal and resource constraints limited the extent to which the DVAP program could provide a meaningful sanction to vehicle owners who did not take the course when ordered to do so."

Legally and logistically, it was difficult to administer the program — though some of the fault belongs with the city. Some cars of DVAP scofflaws had warrants issued for them, but were never seized. This frustration is expressed in a section with the deadpan title, "There are Numerous Legal Impediments to Seizing Vehicles Through the DVAP Program."

"The long period between initial DVAP course notification and the point at which a covered vehicle is eligible for seizure is in many ways the unavoidable consequence of a program in which multiple government agencies use different systems for data management and program administration," the report said. "No single database management system could be used by all parties involved in the program’s administration." (Insert collective sigh here.)

Another flaw? Many of the worst drivers — people with scores of speed-camera violations — simply turned in their plates, presumably for new ones.

"The loss of data due to plate surrenders introduces survivorship bias to this analysis – simply put, because a specific subset of DVAP course participants cannot be traced, and their subsequent driving behaviors are unknown, it is unclear what effects DVAP had on them, and whether these participants differ in meaningful ways from those whose post-course driving records could be analyzed," the report said. "In addition, the small number of owners of out-of-state plates who participated in DVAP could not have any additional registrations traced."

The rules of the program also made difficult to seize vehicles. For instance, DOT said that 1,605 were told to take the course because of their 15 speed-camera or five red-light camera violations in the previous 12 months. And 885 did so.

For whatever reason — either failure to take the course or reoffending within six months of taking the course — 532 drivers were sent notices that their car was subject to being seized. Of those, 231 sought an additional hearing to avoid the seizure. And even though 224 of those hearings ended up in a ruling of seizure, only 159 vehicle owners were mailed a notice that their car would be seized — and only 12 were in fact seized.

Plus, the program had to be scaled back to just city residents "in order to eliminate frequent obstacles in seizing vehicles of non-respondents who live outside the five boroughs."

The agency estimated that the program cost more than $1,000 per participant.

The psyche of a reckless driver

Another interesting finding in the report: The worst of the worst drivers consider themselves to be perfectly safe drivers.

"When asked to rate themselves, all DVAP course respondents said they were 'very confident' or 'somewhat confident' that they are safe drivers," the report said, even though that perception is simply not accurate based on the sheer number of violations DVAP course participants racked up.

"Several people who consider themselves to be very safe drivers actually accrued double-digit speed camera violations on their plates in the year following their DVAP course attendance," the report said. So much for self-awareness.

The DOT cherry-picked personal responses from some participants, including some whose drop in violations was not all that impressive:

“The [course] video regarding how many people actually die from simple mistakes stuck with me," said one 2022 course participant from the Bronx. "It has given me a reminder that driving slow to your destination is important for my safety as well as others.” Has it, though? The report says she reduced her speed-camera violations from 15 in one year to six (though it is unclear if that was in six months or a year).

“I think it was very eye-opening with all the stats that were provided,” added one man from Queens who also took the course in 2022. He reduced his violations from a shocking 41 in one year to 21 (though, again, it's unclear if that was in six months or a year).

What's next?

The DOT is calling for the DVAP program to simply disappear. But the agency is promising a "two-pronged strategy" to rein in reckless drivers — neither of which it has full power over.

First, the agency says it will back bills on the state level to remove reckless drivers, though the report only mentioned one bill, S451/A7621, which would allow the DMV to suspend the registration of any vehicle with five or more red light camera violations within 12 months.

The DOT also said it would "explore opportunities to expand driver education to driver populations more likely to benefit, including inexperienced new and young drivers," such as through a DVAP-style course "in high schools and colleges."

Since neither of those prongs will amount to any tangible road safety in the immediate future, it is unclear what will happen next once the program sunsets and drivers with 15 or more speed-camera tickets are no longer being told they need to take a safety course or risk having their car seized.

Council Speaker Adrienne Adams declined to comment when asked about the program's Oct. 26 sunset. There is no pending Council legislation on reauthorizing or expanding the program. After initial publication of this story, Transportation Committee Chair Selvena Brooks-Powers sent over a statement:

"Holding reckless drivers accountable and keeping our streets safe for all New Yorkers remains a priority. I look forward to reviewing the Department of Transportation’s report on the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program to determine possible next steps."

In its own statement, DOT added:

"Despite the noble intent of the pilot program, DOT’s evaluation found the pilot’s effects on driver behavior to be underwhelming and its path to vehicle seizures to be convoluted, due to the city’s limited legal authority."

Since March 31, when the report's coverage period ended, another 700 vehicle owners have received notification that they need to take the course, which will continue for six more months, the agency said.