The Department of Transportation reaffirmed its commitment to implementing traffic calming and protected bike lanes under the elevated tracks in Astoria on Friday after opponents sued to stop the project.

DOT's redesign will put a protected bike lane on both sides of 31st Street between Newtown and 36th avenues, placing the bike lane between the elevated subway columns and the curb [PDF]. In June, several business owners opposed to the changes swarmed a community board meeting, where they shouted down bike lane supporters and pushed inaccurate claims about bike lanes making streets less safe.

Some of those same businesses are now suing — and doubling down on anti-safety misinformation: The businesses sued in Queens on Friday, claiming the bike lane would "jeopardize" the safety of cyclists and "increase the likelihood of injuries" to pedestrians — despite city data and mounds of research showing protected bike lanes do the exact opposite. It also asserted that the bike lanes would create "impediments for emergency service workers" — even though emergency vehicles can use bike lanes when necessary.

Revealingly, however, the businesses whined in their suit that the project's narrowed vehicular lanes — key to the project's goal of slowing down drivers — "inhibit access to the Robert F. Kennedy Triboro and Ed Koch 59th Street bridges."

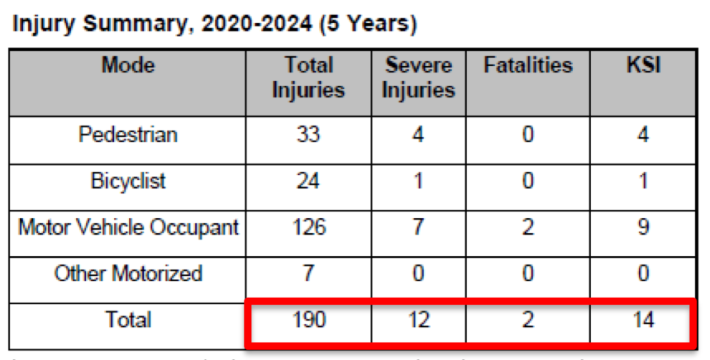

The argument, in short: Let us drive quickly and recklessly through this neighborhood. Since 2020, 190 people have been injured in the project area, 12 severely, and two people have been killed, according to city stats.

DOT's redesign aims to rein in the chaos that puts the street in the top 10 of Queens crash corridors — a status no doubt tied to the strip's place as a "pass-through" for drivers going between the RFK Bridge and the Queensboro Bridge. Per DOT, the "ambiguous space" between the subway columns and the curb add to that chaos by encouraging double parking, "unpredictable vehicle movements" and dangerous, high-speed turns.

Beyond adding bike lanes and narrowing driver lanes to reduce speed, DOT plans to add painted pedestrian islands at intersections to slow down turning drivers.

Reached for comment, DOT was unbowed, and specifically pushed back on a claim in the lawsuit that the agency had not sufficiently engaged with the "community."

"We’ve engaged with 52 different businesses within project limits, and 90 percent provided feedback that has been thoughtfully incorporated into the updated redesign," said DOT spokesman Will Livingston. "This project utilizes common design elements found on streets across the city that comply with local law and ADA regulations. We stand firmly behind this project and will defend our work in court."

In total, 19 businesses and one church sued to kill the safety improvements. The group also sued Queens Community Board 1 for not giving opponents more time to speak against the project in June.

"It is evident that the effort to accommodate cyclists is secondary, a Trojan Horse for the city’s primary goal, creation of 50 miles of protected bike lanes each year as a means to reduce vehicular traffic," the plaintiffs charged in their suit. [The 50 miles of bike lane installation is a requirement of city law.]

In response to the suit, at least one local cycling activist called on bike lane supporters to boycott businesses that oppose the safety fixes.

Council Member Tiffany Caban, Sen. Kristen Gonzalez and Assembly Member Jessica Gonzalez-Rojas signed a letter in support of the project in June.

The project is in the district of Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani, but he has not commented on the project during his run for mayor.

Protected bike lanes have shown to reduce injuries by 14.8 percent on corridors where DOT has installed them, according to city figures. The average reductions are even higher for seniors (22 percent) and pedestrians (29.2 percent).

Lawsuits against DOT's street redesigns rarely, if ever, succeed — court after court has sided with the city's power to make evidence-based decisions about how to organize traffic on its roadways.

Mayor Adams, however, has been more than willing to overrule his DOT and renege on street redesign projects at the behest of his donors.