In February 2015, New York City buses moved at an average speed of 8.3 miles per hour. In February 2025, New York City buses moved at an average speed of 8.3 miles per hour.

New York City has rolled out one bus priority measure after another since then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the MTA first introduced Select Bus Service back in 2008, yet its buses remain the slowest in the nation. Two recent reports explain why — and how the city can have real bus rapid transit to get riders moving.

In the first, New York-based international bus experts Annie Weinstock and Walter Hook argue that the city and the MTA often fail to combine most proven bus-first treatments on major corridors where they can have the most impact. Injstead, piecemeal improvements have barely yielded results.

"New York City’s bus priority measures have never reached the baseline rating of a Bus Rapid Transit corridor," Weinstock and Hook wrote in their study, "How Much Faster Are We Moving?"

"There are at least 18 full BRT corridors in the US and dozens more internationally. These full BRT corridors have generally achieved much higher average speeds, ranging from 11 to 14 mph. Surely New York can do better."

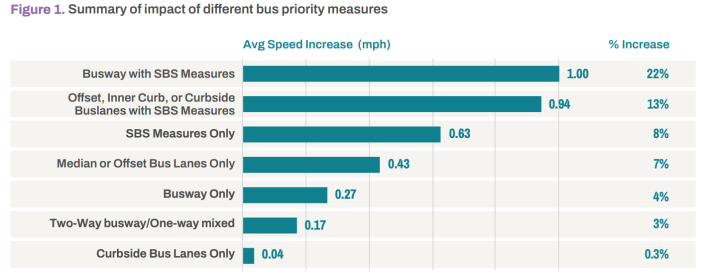

Weinstock and Hook examined every bus idea that the city Department of Transportation and the state-run MTA have rolled out since 2008 to speed up buses — including bus lanes, transit signal priority, bus lane cameras, off-board fare collection and all-door boarding. Taken on their own, none of the measures by themselves did much to move to needle on bus speeds, even bus lanes and even busways, the researchers found.

Busways, for example, have raised bus speeds by just .27 miles per hour, or 4 percent, where they've been installed in the city, the report said. Bus lanes that go in by themselves without any treatments like stop consolidation or off-board fare payment also don't move the needle much. Curbside lanes speed up buses by just .3 percent by themselves. And even median bus lanes, which DOT has moved to as a modern approach, increase bus speeds by a measly 7 percent if they're not combined with other priority measures.

Outside of the 14th Street busway, the city and the MTA haven't combined the most effective bus treatments they have to create true bus-first corridors, Weinstock and Hook argue.

"There hasn't been really a comprehensive effort to do as as much as possible for specific bus corridors," Weinstock told Streetsblog. "It's been very piecemeal, and some of the pieces have worked better than other pieces."

Those kinds of decisions can make a huge difference in how busways work. Buses on 14th Street benefit from bus-only traffic rules and off-door fare collection and on-board bus enforcement cameras. The city's six other busways restrict car traffic via camera enforcement, but don't do much else to ensure buses have free reign of the street.

As a result, bus speeds have increased on 14th Street by 1 mph — a decent percentage — but the next-best busway result has been an increase of just .36 mph on the Main Street and Archer Avenue busways in Queens.

In most parts of the city, local buses don't get to take full advantage of the SBS measures the DOT gives bus routes, the report said, such as on Fordham Road where only the Bx12 SBS has all-door boarding and off-board fare collection, but the five other routes on the corridor do not.

NYC's less-than-BRT

The city has fallen way behind on using the tools and design policies of true bus rapid transit systems, according to Weinstock and Hook, who have worked on BRT projects across the globe.

The MTA has also fallen short on low-hanging fruit. For instance, on high-ridership bus routes Select Bus Service has been effective at reducing boarding delays thanks to off-board fare collection and all-door boarding. Bringing it to buses across the city would be an easy way to speed things up across the system Weinstock said, but the agency has stubbornly refused to consider it.

Even some of the city's more aggressive projects, like the Livingston Street busway, are victim to poor design choices that depart from international norms, they said.

Livingston Street's design of a two-way busway adjacent to a single lane for other vehicles is the first of its kind in the Big Apple. But because DOT allows vehicles to makes left turns across the bus lanes, turning vehicles are still able to block bus traffic. By neglecting to space out stops on Livingston, the design departs from the international standard that places bus stops at least one bus length away from an intersection, which causes buses to either miss traffic lights or block cross streets waiting for the bus in front of it to load and unload.

The report also notes that the city has never built a single enclosed off-board bus-loading station that bus riders can tap to enter and then wait for the bus. And no bus lane design has ever included "severed cross streets" that allow for pedestrians and cyclists to cross a bus corridor but not private automobiles.

These shouldn't be unrealistic asks on bus priority corridors, Weinstock said. In the case of a street like 14th Street, where off-board boarding stations could be put to best use, the street is already a bus-only street. And in the case of severed cross streets, the political fight is essentially the same as any bus lane so Weinstock said the city shouldn't shy away from it.

"If the city wants to show bus riders that they matter as much as subway riders, they can invest even a small fraction of the money and effort that's getting invested into Second Avenue subway. And I think that they have to try on severed streets. It's more of the the political difficulty that you would have with taking taking lanes from cars and all of that," she said.

Weinstock also noted that the issue with the bus treatments is that even aggressive treatments are assigned to specific bus routes instead of the full corridors that serve the buses.

"The first thing we would do is prioritize both routes and corridors," said Weinstock. "SBS has historically been routes, so the DOT and MTA do the measures on the routes, and if any other routes are traveling on that corridor, they might get to use the bus lane, but they don't get all the other priority measures. Whereas BRT would usually be looked at like a corridor, and all of the bus routes will get all of the measures."

To that end, Weinstock and Hook said that in the next iteration of the Street Master Plan, which is due at the end of 2026, the city should scrap bus lane mileage goals. Instead, the DOT should focus on building at least five miles of bronze-rated BRT corridors as determined by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy.

An opportunity to change course

With those failures in mind, a new report from the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee released this week urged the city and MTA to finally embrace real BRT street treatments.

The PCAC report, "BRT for the Boroughs," hits many of the same notes as Weinstock and Hook, pointing out that the city's curbside and offset bus lanes don't meet the standard of truly fast bus service.

"BRT For the Boroughs" makes a series of recommendations for the MTA and DOT. The city should ban left turns across bus lanes and focus on center-running, as opposed to curbside, bus lanes, the report said. The MTA should pilot buses with doors on both sides enable bi-directional bus boarding islands, remove the dated off-board fare payment MetroCard machines from SBS routes and explore installing fare gates at bus stations, according to PCAC.

Crucially, PCAC also called on the city and MTA to work together on two things. One is bringing back SBS service, which Andrew Cuomo killed in 2018 in a shortsighted cost-cutting measure, and running it on bus rapid transit corridors. The other is creating actual bus boarding stations, which would allow both agencies to put money towards the effort to make subway station-like bus stops that, as Weinstock and Hook also argued, would give bus riders some dignity on their commutes.

"PCAC recommends that the MTA play a more central role in the capital construction and operational maintenance of BRT stations," the PCAC report said, urging the authority to "leverage existing in-house talent ... to create robust platform designs and passenger amenities for a true BRT experience."

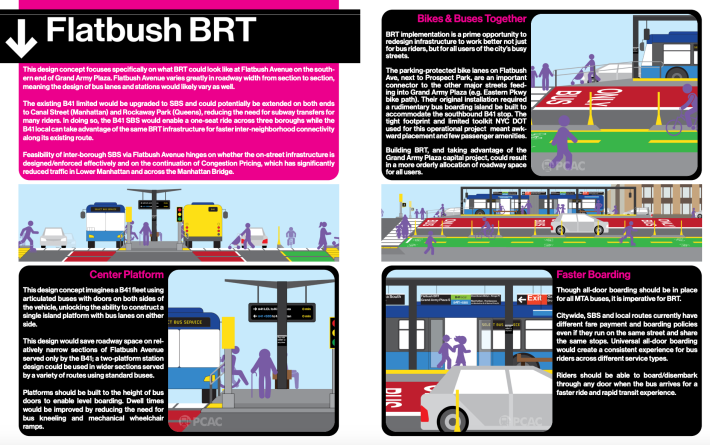

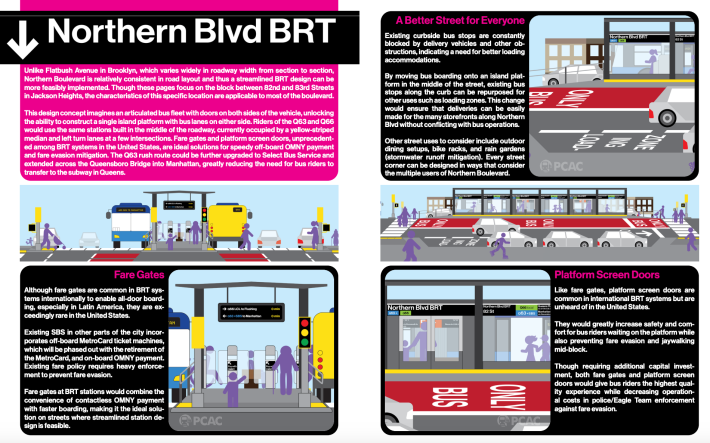

The PCAC report helpfully highlighted out a pair of places where bus rapid transit could flourish: Flatbush Avenue south of Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn and Northern Boulevard in Queens.

In both cases, the report noted, the streets are "long, uninterrupted main roadways which span practically the entirety of their respective boroughs." That means both roads could accommodate center-running bus lanes with bus boarding islands.

On Flatbush Avenue, the MTA should essentially upgrade the B41 Limited to a SBS service that uses all-door boarding and level platforms for faster and more accessible loading of passengers, the report said. The design could be extended to Canal Street in Manhattan and Rockaway Park in Queens to form a three-borough BRT route, PCAC suggested.

Doing so "would enable a one-seat ride across three boroughs while the

B41 local can take advantage of the same BRT infrastructure for faster inter-neighborhood connectivity along its existing route," the PCAC wrote.

On Northern Boulevard, the report suggested trying out fare gates and platform screen doors on existing bus boarding islands, which would be a first in the US. And by making the Q63 Rush route on Northern an SBS route, the BRT service could take pressure off the nearby subway routes.

A calmer version of Northern Boulevard less centered around cars could also complement the fully redesigned Paseo Park in the future, which is where the designers specifically recommended sending micromobility users once 34th Avenue is a complete linear park.

Whether the reports will have an impact on the ground is yet to be seen, though history suggests real-deal bus rapid transit is not exactly barreling down the street.

Mayor Adams has shown no inclination to make the hard decisions that would be necessary to introduce real BRT to the city. The man who took office promising to be the bus mayor has backtracked on a number of key bus improvement projects around the city, falling well short of the legally-required 30 miles of bus lanes per year the city is supposed to install. He recently paused work on the 34th Street busway, and after previously delaying or killing projects on Northern Boulevard, Fordham Road and Flatbush Avenue. The latter project is finally moving forward this year and may even use center running bus lanes with boarding island, but if it goes in it will only be on the piece of Flatbush Avenue north of Grand Army Plaza.

A spokesperson for Democratic mayoral nominee Zohran Mamdani did not respond to a request for comment. Mamdani emphasized on the campaign trail that he wants to focus on the speed of bus service as much as he wants to make them free, and cited the bus rapid transit service in Bogota as something he'd like to bring to New York.

A DOT spokesperson said the agency will review the reports, while insisting the city and MTA's work had sped up buses.

"NYC DOT is committed to improving bus service and has made buses faster, more reliable, and accessible for hundreds of thousands of daily bus riders with new bus lanes and dramatic expansions of transit signal priority and camera enforcement—including through the nearly eight miles of bus lanes currently being installed on Hillside Avenue in Queens," said spokesperson Vin Barone.

A spokesperson for the MTA, meanwhile, inexplicably claimed that the issue of bus rapid transit is "largely an issue within the city’s purview" because it involves the placement of bus lanes. The transportation authority, which operates city buses, declined to comment on the either report's finding or recommendations.