The city has failed to adopt key recommendations by its own appointed experts to curb congestion near the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway after officials reduced the highway from six to four lanes — and the Adams administration may be now using that same congestion as a justification for building a wider highway.

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio's expert panel in early 2020 predicted more traffic on the BQE from Atlantic Avenue to Sands Street if the city painted two lanes instead of three in each direction — but also came up with measures to cut daily car trips by the tens of thousands.

The 72-page report recommended closing or restricting some entrance ramps, and discouraging and diverting car trips away, but none of those changes were ever made.

Mayor Adams is eyeing rebuilding a wider three-lane roadway, with Department of Transportation officials saying that the extra traffic on side streets slowed travel speeds by as much as 30-50 percent in neighborhoods near the Robert Moses-era roadway following the conversion.

DOT recently launched a study to compare three- and two-lane configurations for the massive construction project slated to start in 2027, but locals worry that the agency is stacking the deck for a larger roadway by not making the recommended traffic improvements.

"They’re trying to prove out their three-lane strategy by letting the local communities suffer," said Amy Breedlove, who leads BQE advocacy for the Cobble Hill Association.

Adams administration officials have already made clear that some New Yorkers — including political power brokers like former Brooklyn Democratic Party boss Frank Seddio — are pushing for a re-widened highway, even though politicians up and down the corridor penned a letter to the federal government lobbying for no more than two lanes.

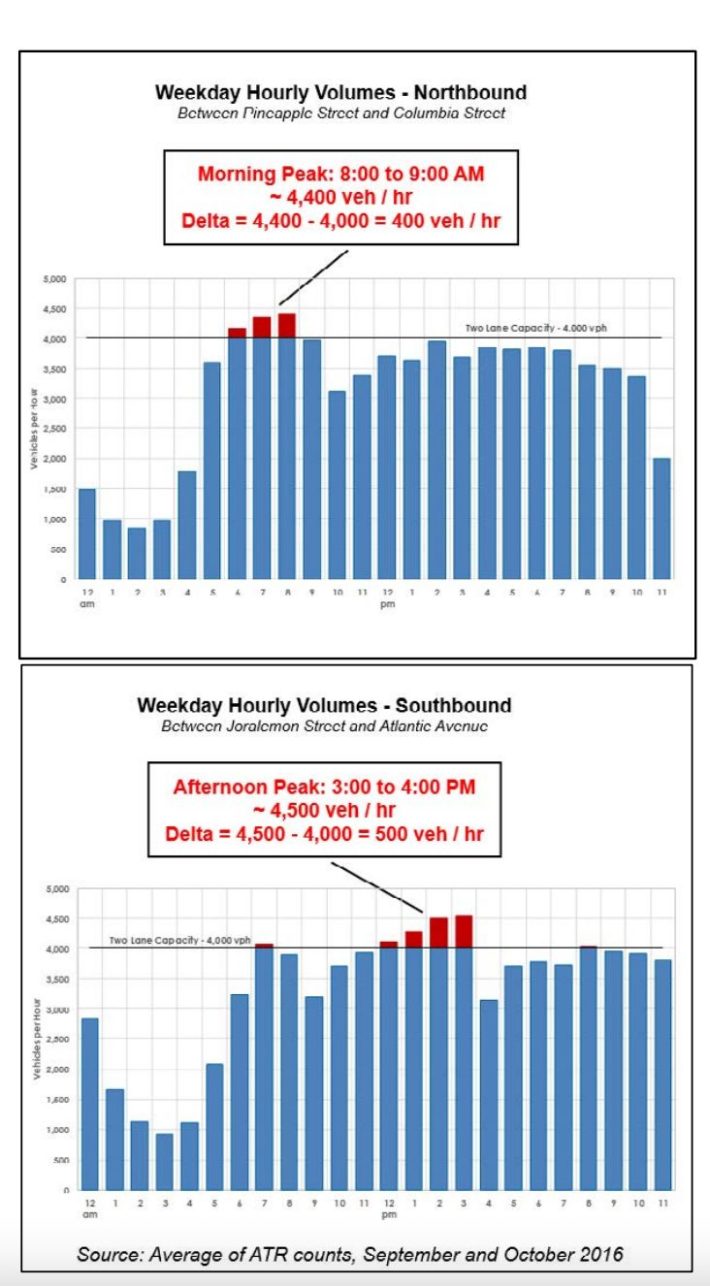

The 17-member BQE panel convened by de Blasio foresaw that a lane reduction meant the roadway "may have several more hours/day (than today) when demand exceeds capacity," but the brain trust still found that two wider lanes would be preferable and feasible.

The group recommended solutions to cut traffic volumes by up to 15 percent, from 150,000 vehicles a day at the time to 125,000. DOT has more recently put the current daily figure at 130,000, or about 87 percent of those pre-COVID numbers.

"This suite of strategies will be critical to demonstrate that the future of the corridor can be planned for a lower capacity without negative effects on surrounding communities," reads the report.

The report's authors urged the city to stick with a smaller BQE as a "blueprint for future planning," rather than making room for more motorists to tear through the Big Apple — even if that faces resistance from car-centric bureaucrats in Albany and Washington, D.C.

"The New York State DOT and [federal] DOT may push back and insist on a positive growth rate. New York City DOT should remain firm in demanding that New York State and U.S. DOTs review the latest in traffic science and consider the many measures proposed in this report to reduce demand," the report reads.

Consultants with the firm of former Traffic Commissioner "Gridlock" Sam Schwartz added a lengthy appendix to the report with a deep dive into managing demand, and found two lanes would work if the city was serious about discouraging more drivers.

They could do so by closing some of the more busy ramps, or restricting them to high occupancy vehicles only, at the Brooklyn Bridge, Atlantic Avenue, and Cadman Plaza.

Almost one-third of Queens-bound BQE traffic exits at the Brooklyn Bridge, and closing that ramp "would immediately reduce demand," according to the report. Only allowing HOVs with two or more people could cut numbers on that ramp by 30-40 percent.

The complicated Atlantic Avenue entrance on the Queens-bound side is "one of the worst designed ramps in New York City," the report notes, and closing it off would reduce car volumes and divert more traffic to the Hugh Carey (former Battery) Tunnel — while getting rid of a notoriously dangerous interchange.

Over the last two years, there have been 167 total reported crashes on the two-block stretch of Atlantic at the highway entrance, killing one person and injuring another 68, or nearly three injuries a month.

"Step one would be to close the ramp," said Kelly Carroll, the executive director of the Atlantic Avenue BID. "This is one of the most deadly areas in my corridor."

The city could also toll the Brooklyn or Manhattan Bridge at prices similar to the tunnel — a charge that many drivers currently dodge by choosing to take the BQE to the free bridges in or out of Manhattan.

The underground tube is similar to the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, but handles about 20,000 fewer daily vehicles, the report notes, leaving plenty of room to take cars from off BQE.

Two modern-width lanes can handle 4,000 vehicles an hour, just 500 below the previous narrower three lanes, and enough for most hours of the day, according to the report.

"What we learned is that you can handle the traffic with four lanes and four safer lanes," said Ross Sandler, a New York Law School professor who was on that panel and served as the DOT commissioner under Mayor Ed Koch in the 1980s. "That still holds true."

Building out three wider lanes at a modern standard would raise capacity to 6,000 vehicles an hour on the cantilever, well above the amount that section of the BQE could handle before the reduction.

Since the state has no plan to overhaul its portions of the BQE north and south of the Brooklyn Heights section, locals worried that a new wider stretch around Brooklyn Heights would induce demand for more driving and lead to more spillover onto local streets — exacerbating the problem the city claims it wants to address.

Many Queens-bound drivers get off the highway before the Carroll Gardens trench and cut through Columbia or Hicks streets, before getting back on the BQE at Atlantic Avenue to bypass the congested below-ground portion, causing the extra traffic on those local streets.

"Basically, Hicks Street has become a parallel BQE," said Carroll.

Since the buried section can't expand beyond its current footprint of wall-to-wall road, added traffic capacity on the cantilever would fill up those neighborhood streets even more, Breedlove said.

"The trench can’t handle it, so all they’re doing is forcing all those cars into local streets," she said. "They’re trying to sell it as the solution, but I don’t see it as a solution and the mayor’s expert panel didn’t see it as a solution."

De Blasio shrunk the lanes in 2021, and DOT at the time vowed to launch a "comprehensive traffic management and monitoring plan," and a "neighborhood protection plan to minimize disruption to motorists and nearby residents," but locals said the agency yet to produce either.

Frustration grew at a Thursday update about the BQE DOT gave to Community Board 6's Transportation Committee, where residents called on the city to do more.

"Absolutely nothing’s been done using traffic patterns," said Columbia Waterfront District resident Bruce Mazer at the virtual meeting.

Mazer said the agency could discourage cut-through traffic on Columbia by banning drivers from getting back on at Atlantic Avenue.

"There are absolutely things that can be done, I just don’t feel like they’re being explored," he said.

DOT's chief strategy officer told the civic committee that trucks coming from the nearby freight ports still needed access to the BQE.

"We have looked at it closely, we’ve made a number of changes and this is not one of the changes that is feasible due to the significant freight in the area," said Julie Bero. "Those trucks will always come out onto Columbia as long as that operation is there."

The Department is considering redesigning the Atlantic Avenue intersection, Bero added.

Agency spokesman Vin Barone said officials are implementing all recommendations they deem feasible.

Closing or limiting ramps would require approval from the Federal Highway Administration, but DOT will study some closures.

"Substantial" traffic has already shifted to the Carey Tunnel, Barone added, saying DOT put up travel time info on digital signage comparing the tolled facility to the free East River bridges.

Charges on the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges would not divert "significant" traffic from the BQE, Barone added, citing MTA's congestion pricing environmental assessment.

The share of East River crossings via the Queens-Midtown and Hugh Carey tunnels would grow from 11 to 17 percent under one congestion pricing scenario that equalizes those charges, according figures buried in an appendix to the lengthy document.