The city has scaled back a modest proposal for a pair of protected bike lanes in an unsafe area of central Brooklyn following predictable opposition from car-focused locals.

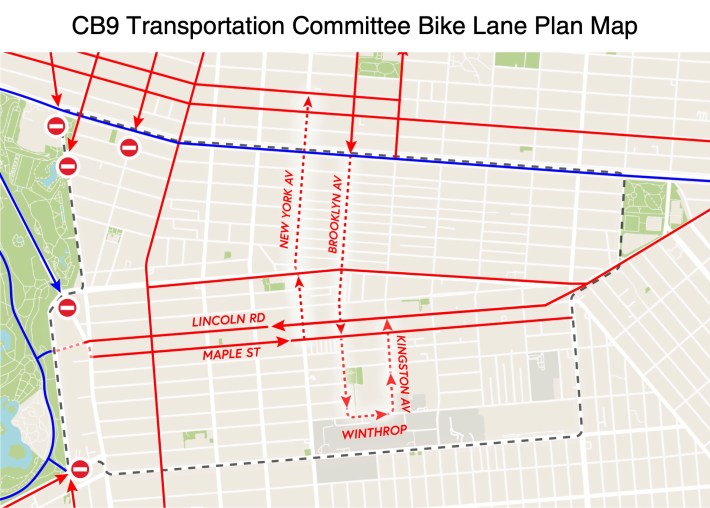

The Department of Transportation had planned to install parking-protected curbside lanes northbound on Kingston Avenue and southbound on parallel Brooklyn Avenue between Empire Boulevard to Winthrop Street — just nine blocks in a place desperate for more extensive safe biking networks.

But the agency shelved the upgrades on the most-dangerous northernmost blocks after some locals pushed back at a community board meeting last year, according to a presentation DOT quietly published in June [PDF].

Activists were furious that such a modest initial proposal had been truncated further — an ongoing trend in the waning days of an administration riddled with corruption allegations.

"We’re never going to get a bike network if we’re going to do this block-by-block warfare where neighborhoods get to opt out," said Jon Orcutt, director of advocacy at Bike New York. "Let’s hope for a new approach in 2026."

The agency did not withdraw its plans to paint unprotected east-west bike lanes on Rutland Road and Fenimore Street, connecting west from Brooklyn Avenue to Flatbush Avenue.

Why safety is needed

DOT's initial proposal last year came after local school principals demanded a redesign to curb rampant speeding and drag racing on the wide roads outside the more than 10 schools in the area.

Crash injuries have been rising on the corridor over the past year, and protected bike lanes could have reduced crash injuries by 15 percent, and by 21 percent among pedestrians, according to DOT.

The city has studied effectiveness of protected bike lanes for more than a decade and across wide swaths of a city, and they have proven to increase safety, especially for people on foot.

Protected bike lanes typically cut total injuries by 14.8 percent, and serious pedestrian injuries or deaths by 29.2 percent, according to a citywide 2022 review of DOT projects spanning 2005-2018.

But stats didn't sway some residents, according to the head of Community Board 9's Transportation Committee.

"It all comes down to the fact that some people don’t trust the numbers or just don’t know the numbers," Ethan Norville told Streetsblog.

Residents' opposition was additionally fueled by a successful effort by Hasidic leaders to convince Mayor Adams to overrule his own DOT and remove part of the Bedford Avenue protected bike lane after a video emerged of a child being struck by a cyclist on the lane.

"The Williamsburg incident on those bike lanes really did stir up [things] with our bike lane," Norville told Streetsblog.

Locals were also concerned about how narrowing the road could inconvenience motorists and emergency vehicles, especially on the slimmer section north of East New York Avenue, Norville said.

"Although this neighborhood is not a transit desert, a lot of people appreciate being able to drive here. Some people don’t want to quite give up that space to cars yet," he said.

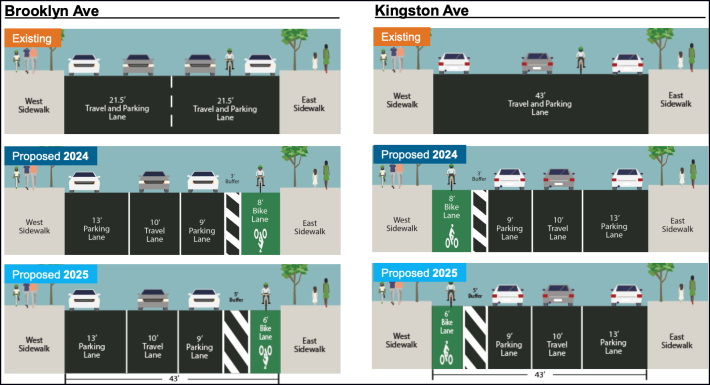

Some residents said that DOT's proposal to redesign the northern stretch of Brooklyn Avenue from two travel and parking lanes into one travel lane and two parking lanes would clog traffic, because it would only take one person to double park to block moving vehicles.

"There’s double parked vehicles, there’s deliveries, taxis. At the moment there’s a way to skirt around it, but when there’s one lane, whether it’s a bike lane or an extended parking lane, pretty much it’s going to be a disaster 10 times over," said one man in a representative comment at a November committee meeting.

However, ambulances and firetrucks can use protected bike lanes in emergencies, even when the main roadway is filled with traffic, and that reasoning essentially argues that the city's roads should be designed around drivers being able to illegally park in the roadway.

It also ignores the fact that DOT has installed this type of design on streets all over the city.

Past efforts to install even unprotected bike lanes have been opposed by CB 9 and by area pols for a decade. The Transportation Committee did try and push the envelope a little bit, by proposing a network of bike lanes in spring of 2024 on Brooklyn Avenue and New York Avenue to the west that would have linked up with Eastern Parkway, but DOT's response was more focused on the schools east of Brooklyn Avenue.

DOT again modified its plan, this time nearly whole-cloth from a set of demands the civic committee passed in November [PDF].

That included leaving out the northern two blocks, scaling back the repurposing of car storage at corners for better visibility – a design known as daylighting – and narrowing the actual protected bike lanes from eight feet to six in favor of widening the painted buffer.

"People here don’t quite believe that bike lanes will bring safety because of the mechanics of it," Norvell said. "If you’re trying to get out of your car, you have bike traffic on both sides."

DOT's latest reversal leaves untouched the intersections with the most crash injuries at Lefferts Avenue, which is also right outside an all-girls yeshiva, Beth Rivkah. The agency found 80 percent of drivers were breaking the speed limit outside that school.

"Protected bike lanes make streets safer for pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers alike," said Ben Furnas, executive director of Transportation Alternatives. "It's disappointing that the Adams administration is weakening another street safety project, and it's baffling that the portion of the plan being watered down is precisely the part of the street with the most crashes. Brooklyn schoolchildren deserve safety."

DOT counted 158 injuries in the project area between 2019-2023, with 71 percent of severe injuries being pedestrians and cyclists, and kids making up one-in-seven cyclist and pedestrian injuries. Last year, car crashes injured 32 people, four of those seriously – the highest numbers since 2021 – and five of the victims were children.

Officials will still move ahead with the southern section of the project in the coming months, but the result will make but a little dent in a district where there are zero protected bike lanes, except for Eastern Parkway, which dates back to the 1870s.

"It was a pretty modest proposal to begin with," Orcutt said. "There are some weird little stubs of protected bike lanes across the city, and I hope this doesn’t become one of those."

DOT did not respond to questions for this story.