The push for banning parking at intersections keeps growing as 10 community boards have now voted to endorse the safety tool, but officials continue to hesitate implementing daylighting at all of the city’s 40,000 intersections.

The civic panels — which represent nearly 1.5 million New Yorkers — are part of a growing call for the city to stop exempting itself from state law that requires no parking at corners, which creates more visibility.

“You can say, ‘Well we’re losing parking,’ but you’re losing parking [that causes] serious injury and death — that’s pretty indefensible,” said Upper West Sider Ken Coughlin, a member of Community Board 7, the latest board to vote on a daylighting resolution on Tuesday night.

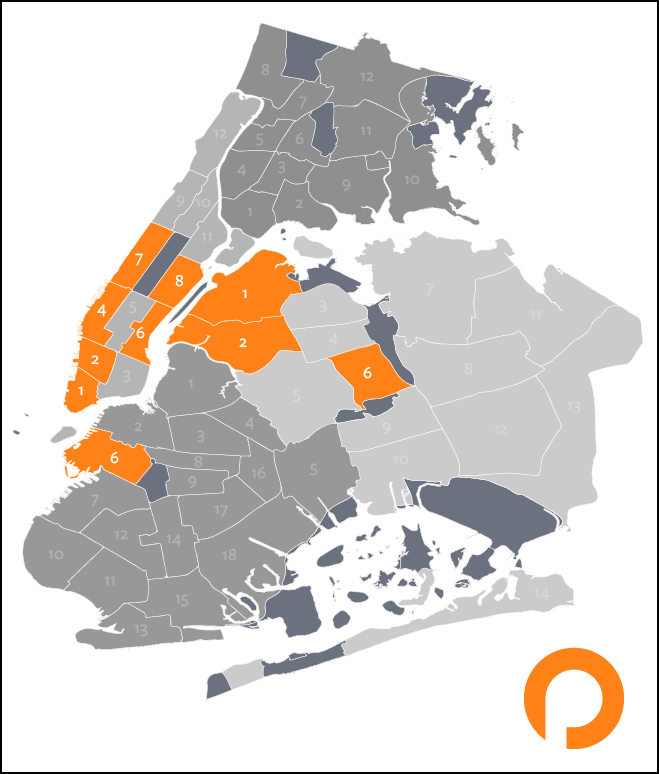

The uptown panel’s full membership voted unanimously — with one abstention — in favor of universal daylighting, and now half of the borough’s 12 community boards have signed onto the effort.

State law already bars parking within 20 feet of crosswalks, but the city has long exempted itself from that provision to provide more space for vehicles at intersections, where, according to the city's own data, 55 percent of pedestrian traffic deaths and 79 percent of injuries occur.

The Adams administration promised to daylight 1,000 intersections a year after an NYPD tow truck driver killed 7-year-old Kamari Hughes while turning at an intersection with poor visibility in Fort Greene. But city officials have insisted that the well-established safety measure is not appropriate at every intersection.

Other municipalities have embraced daylighting more aggressively, like Hoboken, New Jersey, which hasn’t had a traffic death in seven years.

The civic push began in western Queens’s Community Board 1 last June, which voted for universal daylighting after a driver fatally struck 7-year-old Dolma Naadhum earlier that year at an Astoria intersection where cars routinely parked right up or in the crosswalk and obstructed visibility.

Inspired by the move, other boards in Queens, Brooklyn, and Manhattan soon followed, and at least one such panel has passed a universal daylighting resolution each month for six months straight, making it clear that the measure enjoys wide support, said one advocate.

“Improving the crosswalk experience really resonates with New Yorkers. We all use them; we all know the cramped feeling, the anxious need to peer past parked cars to see what's coming,” said Carl Mahaney, director of StreetopiaUWS (which shares a parent company with Streetsblog). “It’s a two-for-one, because prohibiting cars from that space creates the opportunity to add useful stuff like bike parking, seating, and plants — things that make the city a more comfortable and pleasant place to be.”

Elected officials — including north Brooklyn lawmakers in November and central and southern Brooklyn pols in January — have also thrown in their support with letters to Department of Transportation Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez.

During a City Council oversight hearing last year, Rodriguez defended the city’s decision to opt out of the state law on the grounds that daylighting is “not the right solution everywhere.” In some instances, a parked car at an intersection prevents another driver from cutting the corner and making a faster turn.

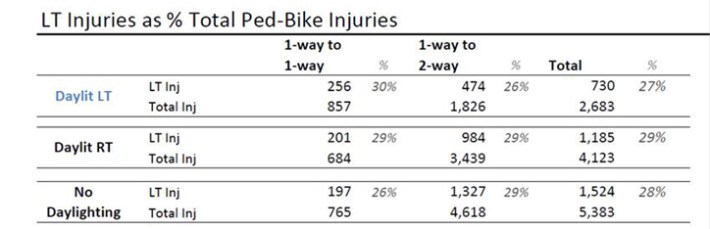

But the only data DOT has produced to back up that case is an excerpt of a study of left-turn crashes at 3,000 intersections between 2009-2013, which Streetsblog obtained last year — six months after demanding it under the Freedom of Information Law. The agency only provided some of the requested data.

The table showed there was a slightly higher percentage of bike and pedestrian injuries at crossings of two one-way streets that banned parking at the corner — albeit without a physical obstruction — and the agency also at the time admitted it has never done a "comprehensive analysis of daylighting safety."

Coughlin suggested the more likely reason the agency has hesitated to follow state law is the political and dollar cost of removing tens of thousands of parking spots and replacing them with hard infrastructure, in a city where even swapping out some spaces for Citi Bike docks can cause a local uproar.

“Their resistance is both [that] they don’t want to do the big parking removal, and also it’s expensive ... to harden the infrastructure at every corner and it will take a while,” the Manhattanite said.

DOT spokesperson Mona Bruno said the agency will review the requests and that it is "using every tool available to implement safer street designs, including a historic commitment to improve visibility at 1,000 intersections each year through daylighting."