Anything is better than nothing.

Department of Transportation officials flat out said that doing "nothing" is not an option amid heated criticism on Monday from residents of central Brooklyn over a plan to install the neighborhood's first protected bike lane in 150 years.

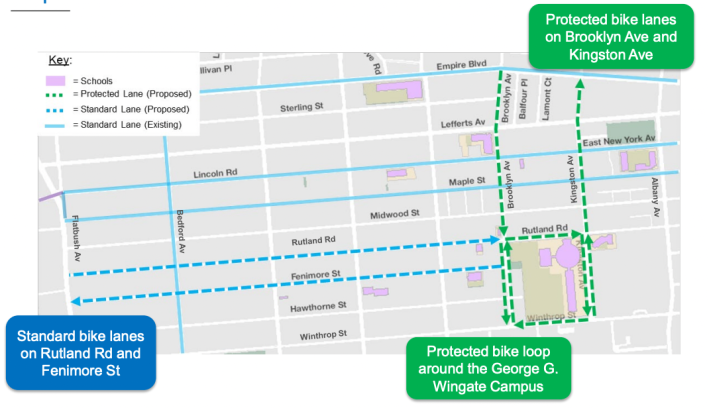

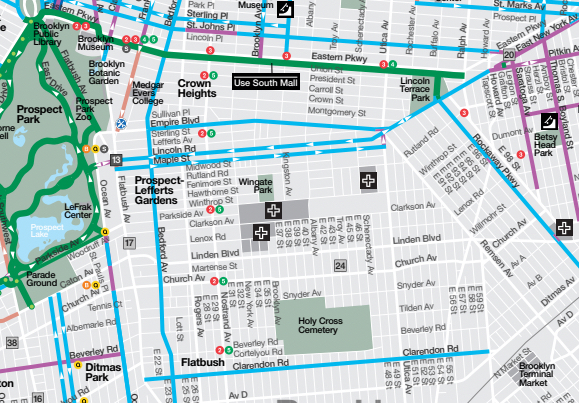

There hasn't been new separated cycling infrastructure in Community Board 9 since Olmsted and Vaux's Eastern Parkway in the 1870s, but DOT officials vowed to break the status quo of traffic violence plaguing the area by installing a network of protected bike lanes on Kingston and Brooklyn avenues, where drag racers speed past the more than 10 schools in the area.

"We’re not going to do nothing," DOT's Director of School Safety Nick Carey told dozens of people stuffed into the CB 9's Nostrand Avenue office. "Both corridors have a concentration of schools, a concentration of injuries."

The agency first presented its proposal in June [PDF] for the protected bike lanes between Empire Boulevard and Winthrop Street, an area with more than 10 schools and rampant speeding yet zero protected bike lanes.

But attendees at the meeting unleashed reams of debunked arguments against life-saving bike infrastructure, falsely claiming the protected lanes would endanger children, and arguing the neighborhood didn't need them.

"The idea of this protected bike lane on that corridor, especially on Brooklyn [Avenue], where people live that need to go their cars and pick up their children and whatnot, I think that’s a bad idea," said Yossi Kahan, a school bus driver and the Director of Transportation for the United Lubavitcher Yeshiva. "A protected bike lane actually makes it dangerous for the children getting on and off the bus."

One former board chair also railed against the new project, claiming he convinced DOT leaders in the 1980s to back off an effort to redesign the street.

"This idea showed up in 1984, I was the chairman of this community board for 34 years," said Rabbi Jacob Goldstein. "I know it’s good for the bike people — they’re probably the ones who are pushing it — but you’re not taking into consideration the bigger picture of the community and the people who live in the community."

He then also claimed that bike lanes would lead to children being "struck."

But DOT data show that protected bike lanes actually mostly benefit people on foot, not cyclists. And the paths reduce all traffic injuries on average by 15 percent across, and by as much as 21 percent among pedestrians, according to citywide stats from 2007 to 2017.

DOT officials knew they were not facing a friendly audience; efforts to install even unprotected bike lanes have been opposed by the volunteer civic panel and by area pols for a decade.

And local electeds — including Assembly Member and Brooklyn Democratic Party boss (and bike lane skeptic) Rodneyse Bichotte-Hermelyn — opposed DOT's previous effort to build a network of bike lanes just to the south in Community Board 17 three years ago.

But injuries are already high.

There have been a staggering 271 reported crashes in the project area over the last five years —more than one every week — injuring 144 people, including 32 pedestrians and 19 cyclists, according to Crash Mapper.

The two roadways are wide with low traffic, encouraging routine speeding, according to DOT.

On a block of Kingston Avenue sandwiched between George Wingate High School and Kings County Hospital south of Rutland Road, agency radars found that 95 percent of drivers exceeded the speed limit, with some as fast as 41 miles per hour, well above the citywide legal limit of 25 miles per hour.

A crash with a pedestrian at 45 miles per hour has an 80 percent likelihood of killing the person on foot, the agency noted in its presentation.

There was also evidence of drag racing, such as donut tire markings on the street, Carey noted.

As such, the current chair of the Transportation Committee broke with the past, adding that local school leaders want the city to make the streets safer.

"There are principals begging for these to be installed," said Ethan Norville.

Cars parked right up against intersections also block visibility for pedestrians and drivers to see each other, especially children, so officials plan to cut two-four private vehicle storage spots per block at corners and replace them with curb extensions, a street design known as daylighting.

The agency's new redesign includes protected bike lanes going north and south on Kingston and Brooklyn, along with a loop of separated cycle paths around George Wingate High School.

The sections of Brooklyn and Kingston avenues along the George Wingate school's campus, between Rutland Road and Winthrop Street, will be two-way bike paths, creating a safe way to cycle around the entire facility.

The agency also proposed unprotected east-west bike lanes on Rutland Road and Fenimore Street, connecting west from Brooklyn Avenue to Flatbush Avenue.

One local voiced support for the project as well, saying it would make him feel safe on his commute.

"As a construction worker who often is working in Brooklyn, I’m biking early in the morning, in the dark in the winter, and having a protected bike lane feels very important to my safety and my co-workers’ and union brothers’ safety," said Charlie Cauman-White.

DOT officials hope to start the work in 2025, though it is not clear what the final plan will be.

The city's safe streets projects have long focused on wealthier and whiter parts of the city during the first decade of the Vision Zero initiative, a Transportation Alternatives report found earlier this year, but DOT Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez has emphasized that he wants to redesign streets in more working-class communities of color as well.

The agency has started rolling out protected bike lanes in neighborhoods like East New York and parts of the Bronx, a borough where new bike lane mileage has steadily increased from 5.2 miles in 2019 to 26 miles last year, including 10 miles of protected paths, according to DOT.