As Vision Zero celebrates its 10th anniversary this month, one word stands out about all when analyzing its success: Meh.

The city has spent hundreds of million dollars on street improvements that have, in fact, improved safety and reduced danger on the streets. But the safest streets are in white neighborhoods while the benefit of city improvements has not extended to low-income communities and communities of color, according to a new report from Transportation Alternatives.

First, the good news: Last year, there were 103 pedestrian fatalities — a drop of 42 percent from the 178 pedestrians who were killed in 2013, the year before Vision Zero began. The annual pedestrian fatality average in the Vision Zero-era (127) is a 28-percent drop from the 178 deaths in 2013.

And total traffic fatalities during the 10 years of Vision Zero — north of 2,550 people — were 16 percent lower than the decade prior to implementation, when more than 3,000 people were killed. The result is a difference of more than 450 lives, the group said.

"Vision Zero has saved hundreds of lives," Transportation Alternatives said in a statement.

But that's where the great news ends. Perhaps the saddest failure of Vision Zero is its inequity.

Whiter, wealthier communities have safer streets than 10 years ago, while lower-income communities and communities of color have experienced an increase in traffic violence, the group's number-crunch showed.

"It’s clear the program has not been fully or effectively implemented in neighborhoods of color and with lower incomes," the group said in a statement.

Community boards with majority-white populations experienced a 4-percent decrease in traffic fatalities while community boards with majority-Black populations experienced a 13-percent increase and community boards with majority-Latino populations had a 30-percent increase.

Looking more broadly, the 10 community boards with the highest percentage of residents of color had a 20-percent increase in traffic fatalities.

"This doesn’t mean Vision Zero doesn’t work, but the opposite: it only works as well as it’s implemented and prioritized," the group said. "Vision Zero can make every neighborhood safer, but it must be fully and effectively implemented everywhere."

Drilling that point home, Transportation Alternatives pointed out that roadways that haven't gotten street safety improvements remain dangerous. The top 1 percent of the city's most dangerous streets were the site of 269 deaths between 2014 and 2023, which comprised 11 percent of total fatalities, the group said. Those streets include:

- E. 138th Street in the Bronx (7.1 fatalities per mile, 12 deaths)

- Graham Avenue in Brooklyn (5.8 fatalities per mile, 9 deaths)

- Canal Street in Manhattan (6 fatalities per mile, 9 deaths)

- Woodhaven Boulevard in Queens (4.4 fatalities per mile, 18 deaths)

- Bay Street in Staten Island (3.1 fatalities per mile, 9 deaths)

So here's what the Vision Zero era looked like on E. 138th Street:

The Department of Transportation, which has been charged under the current and previous mayor with carrying out Vision Zero took a much broader view of the equity question. The agency did not dispute TransAlt's numbers, but said that it is working hardest in areas of the greatest need — both in terms of income as well as past history of neglect.

“Safety Improvement Projects [are] slightly more concentrated in neighborhoods of high- or very-high poverty than in lower-poverty areas," said spokeswoman Anna Correa. "We’ve seen the greatest decreases in pedestrian fatalities both in neighborhoods with high poverty rates and the highest levels of non-white residents. Our commitment to equity influences where we prioritize our work, weighing neighborhood race and income, density, and history of past projects.”

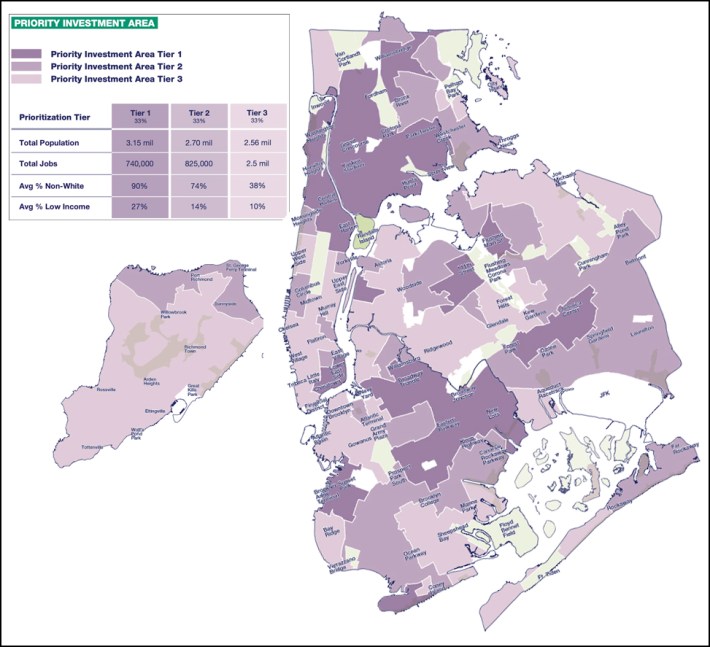

The agency said that just prior to Mayor Adams taking office in 2022, it created three bands of "priority investment areas" [page 19 here] that "units within NYC DOT incorporate ... into their work process as they develop and prioritize projects for implementation." (The quote, ironically, comes from the city's Streets Plan, a document required by law — the same law that mandated the construction of 50 miles of protected bike lanes and 30 miles of dedicated bus lanes every year. The Adams administration missed that goal last year.)

The agency did not provide a breakdown of projects in each priority tier.

What worked

Vision Zero works in specific cases of concerted, long-term city action to redesign streets. For example, when the former de Blasio administration began Vision Zero, Queens Boulevard had earned a gristly nickname as "The Boulevard of Death." But since Vision Zero, there have been just 10 total traffic deaths on the 7.5-mile roadway, down from the 18 pedestrians who were killed by drivers on the street in 1997, Gothamist recently reported. During three calendar years, there were no fatalities at all.

Yo! Some beautiful #bikenyc Monday visuals to wake you up!

— Streetfilms (1,098+ videos!) (@Streetfilms) February 5, 2024

QUEENS BLVD final segment looks done! Here are some before/afters to show you. Hopefully it gets more protection but it feels safe enough.@StreetsblogNYC @bikenewyork @QnsBPRichards @NYC_DOT @TransAlt @LAShepard221 pic.twitter.com/gI2nGVjkMc

By comparison, during the 10 years of Vision Zero, there were 40 traffic deaths on Atlantic Avenue, where major road safety projects have been virtually non-existent (until last week, when long blocks were cut down with the addition of new traffic signals, as Streetsblog reported).

"To be successful and save lives, our leaders need to implement this program with the financial resources, political backing, and urgency it needs,” said Danny Harris, the executive director of Transportation Alternatives. “Vision Zero isn’t just a slogan, but a call to action: we must design streets that keep New Yorkers safe. We fought to bring this lifesaving program to New York City and we will keep fighting until we’ve hit Vision Zero – not Vision 259 – and everyone in all five boroughs can walk, bike, drive, and take transit without fear of death or serious injury.”

Given the lofty goal of its name, Vision Zero has been underwhelming when judging strictly by citywide fatality numbers. In 2013, the last full year before Vision Zero began, there were 296 road fatalities. In 2023, after 10 years of the initiative, that number dropped to 258 — a decline of almost 13 percent. But death counts have ebbed and flowed over the years — and they have always been above 200:

- 269 in 2022

- 284 in 2021

- 269 even in the pandemic year of 2020

Transportation Alternatives said that any declines in pedestrian deaths could be linked to the state legislature's decision in 2014 to allow the city to reduce its speed limit from 30 to 25 miles per hour, the city's 2,000 school zone speed cameras, plus the installation of 6,000 "leading pedestrian interval" signal timings that give pedestrians and bike riders a three- to seven-second head start at stop lights. It is true that intersections with LPIs have reduced pedestrian fatalities and serious injuries by 34 percent.

But fatalities are not a statistically accurate way of gauging of Vision Zero's success:

And 2023 was especially deadly for bike riders – though there have been other years, according to city stats, that have horrified the ranks of New York City cyclists. But higher numbers of cyclists deaths are a double-edged sword: The number of cycling trips is up more than 70 percent since 2013, but the amount of bike infrastructure has not kept up, the group added. Nearly all bike riders killed during the first decade of Vision Zero were fatally wounded on a street with no protected bicycle infrastructure, TA said.

That grim statistic is not likely to change much during the Adams administration, given that the mayor has said he is more concerned about getting sufficient "community outreach" on cycling infrastructure projects than he is in hitting his legal requirement of building 50 miles of protected bike lanes every year (last year, he did 33). Mayor Adams does not have many projects in the pipeline for 2024.

During the Vision Zero era, injuries have remained high — last year, they again exceeded the first full year of Vision Zero, as they have many times during the 10-year initiative:

Why is that?

However vociferously drivers complain about how much space they've lost to bike lanes and pedestrian plazas, the main space hogs are bigger cars and more of them.

Traffic modeling expert Charles Komanoff analyzed the latest U.S. Census data and found that the number of passenger vehicles owned by city residents jumped 12.1 percent between 2012 and 2021, from 1.85 million to 2.1 million.

TA was quick to point out that Vision Zero would have experienced greater gains if there were fewer and smaller cars.

"But as more and bigger cars and trucks come to New York City – as they have over the past decade – the 'safe systems approach' that underlies Vision Zero grows ever more important and essential to save lives on our streets."

That "safe systems" approach is simply overwhelmed by cars, big and small — and not, as has long been pointed out, by e-bicycles and mopeds. During the Vision Zero era, drivers of cars, trucks, and other large vehicles caused more than 99 percent of pedestrian fatalities, but the rise of SUVs and larger vehicles has become a bigger slice of that sickening pie: Last year, SUV drivers killed 70 people, 43 of whom were walking or riding bikes.

Over the past decade, nearly two-thirds of fatally struck pedestrians were killed by SUVs, trucks, or other large vehicles. Do the math: SUV registrations jumped 21 percent in New York City between 2016 and 2020. As a result:

In 2013, according to city stats, 15,478 crashes were caused by SUVs or trucks, injuring 22,567 people. But 2023 the number of crashes caused by SUVs or trucks increased to 21,331 (up 38 percent) and the injuries rose to 30,291 people (up 34 percent).

Yet New York City is not contemplating taking action against these mega-cars. Paris successfully passed a resolution tripling the parking fees on big cars, but New York isn't even considering it. Perhaps America is, indeed, a free country — free for one person to pollute and congest his neighbors' streets. (DOT declined to comment on this.)

Beyond SUVs, there is just so much driving going on: Other statistics suggest that the total number of vehicle miles traveled in 2023 hit an all-time record, and is up 31 percent since the depth of the pandemic.

So what have we gotten for all our money? According to the Independent Budget Office, the city has spent $210 million on Vision Zero projects from 2014 through 2019, then budgeted almost that much for just two years, 2020 and 2021. And DOT Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez testified last year that the city now spends about $250 million per year on Vision Zero.

Taken together, that's about $1 billion — a small investment on the $8.3 billion the city has saved from the overall reduction in traffic deaths, a figure that includes lost wage and productivity, medical expenses, administrative expenses, motor-vehicle damage, employers’ uninsured costs, and value of lost quality of life, Transportation Alternatives said.