Jersey City's transportation transformation under former Mayor Steve Fulop came thanks to his fateful decision to centralize control of the public realm under little-known Director of the Department of Infrastructure Barkha Patel — a concept advocates want to bring across the river to New York City.

Patel worked under Fulop for a decade, rising to the role of Chilltown's first ever Director of Infrastructure. In that position, Patel oversaw Jersey City's streets, parks, transit, and public facilities and spaces. She left office late last year at the end of Fulop's term.

"She's our Janette Sadik-Khan," said Bike JC Vice President Tony Borelli, referencing New York City's much-lauded former transportation commissioner, who introduced parking-protected bike lanes and expanded car-free pedestrian plazas in the five boroughs.

Former New York City Mayor Eric Adams appointed a "chief public realm officer," Ya-Ting Liu, who worked for one of Adams's deputy mayors. But Adams did not attach the level of authority and resources Fulop handed Patel and her Department of Infrastructure — much to the chagrin of Big Apple advocates who'd hoped the new role would better marshal the city's policymaking silos.

Creating a central role attuned to agencies like transportation, parks, police and sanitation is key to expanding transportation alternatives and realizing Vision Zero's goal no traffic deaths, Patel told Streetsblog.

"There is a natural link between all of these things that we are building, and so these things need to be under one umbrella," she said in a recent interview. "By doing that a city is really signaling that they are taking seriously the importance of the public realm.

"One of the big things are making Vision Zero not just a policy that the city adopted but something that we implemented as a regular practice."

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio brought Vision Zero to New York City in 2014, but the city's various departments still work at cross-purposes — whether it's the NYPD's lack of interest traffic enforcement, Parks's neglect of greenways or rampant illegal parking at all levels of government. Liu does yeowoman's work tending to these disparate agencies, but lacks authority to order anyone around.

New York City advocates who fought for a public realm czar during the Eric Adams years recently called on Mayor Mamdani to empower the position, which operates within the office of Deputy Mayor for Operations Julia Kerson, to fulfill his vow to make the city's streets "the envy of the world."

"With the new administration, there are so many huge opportunities on the horizon — expanding school streets and plazas, activating the public realm for the World Cup, building out Low Traffic Neighborhoods — but without coordinated and politically-empowered leadership, these wins will be much harder to achieve," said Sara Lind, co-executive director of Open Plans, which shares a parent organization with Streetsblog.

Jersey City's new mayor, James Solomon, has been critical of his predecessor, — who now heads the Partnership for New York City, and recently accused him of saddling the city with a huge deficit equal to nearly 30 percent of its annual budget.

But at the same time, however, Solomon has nothing but praise for Patel.

"Barkha Patel has been a dedicated public servant who delivered real results for Jersey City residents," Solomon said in a statement provided to Streetsblog. "Her work on Vision Zero, safe streets infrastructure, sustainability, and our parks system made our city more livable and safer for families. I'm grateful for her service and wish her well in her next chapter."

Patel's results are crystal clear in the data. Cycling in Jersey City tripled as a commuting mode between 2019 and 2024, according to a recent update to the city's transportation master plan, as the protected bike lane network grew from zero to 25 miles under Patel's watch. Today, one-eighth of the city's streets have a protected bike lane.

"That’s obviously a big change and the biggest reason by far is the infrastructure she presided over," said Borelli.

Jersey City was the first Garden State municipality in the state to adopt Vision Zero, and Patel used her office to push a crash death reduction strategy.

"One of the big things is making Vision Zero not just a policy that the city adopted but something that we implemented as a regular practice," she said.

More than half, or 57 percent, of residents commute to work via transit, walking or bicycle, according to Patel.

The city's neighbor to the north, Hoboken, has also been a beacon of hope for street safety advocates by reducing crash fatalities to zero since 2017 — in large part thanks to aggressive parking bans near at corners for better visibility, a street design also known as daylighting. The Mile Square City removed motorists from blocking bike and bus lanes with a promising camera enforcement pilot last year, which is currently in legislative limbo.

Wide portfolio

Patel joined the Fulop administration in 2016 and became its transportation director two years later, before heading he newly-formed Department of Infrastructure in 2022.

That wide-ranging portfolio allowed her to cut across the usual agency turf wars that slow down projects, which New York City should take note.

“That was a really great position to be in," Patel said. “We were able to fold in the different disciplines into every project that we do."

Former New York City Mayor Eric Adams appointed a "chief public realm officer," Ya-Ting Liu, but did not attach enough authority and resources to her office the way Patel's Department of Infrastructure operated. It's unclear whether Mayor Mamdani plans to continue the public realm czar role.

Borelli said it was crucial to have "who has authority over all the puzzle pieces on the ground in the city, and then give them the authority and resources to try things and learn from them and iterate on them."

The crown jewel that Patel and safe streets boosters mentioned over and over was the redesign of Bergen Square. The city turned the forlorn crossing, dominated by surface parking lots, into green space with benches and tables, bus shelters, a raised two-way bike lane and bike racks.

The revamp also included painted markings nodding to its long history as one of America's oldest town squares, dating back to the Dutch colonial era in the 1660s.

"What used to be a dangerous intersection with parking lots is now a vibrant public space," said Morgen.

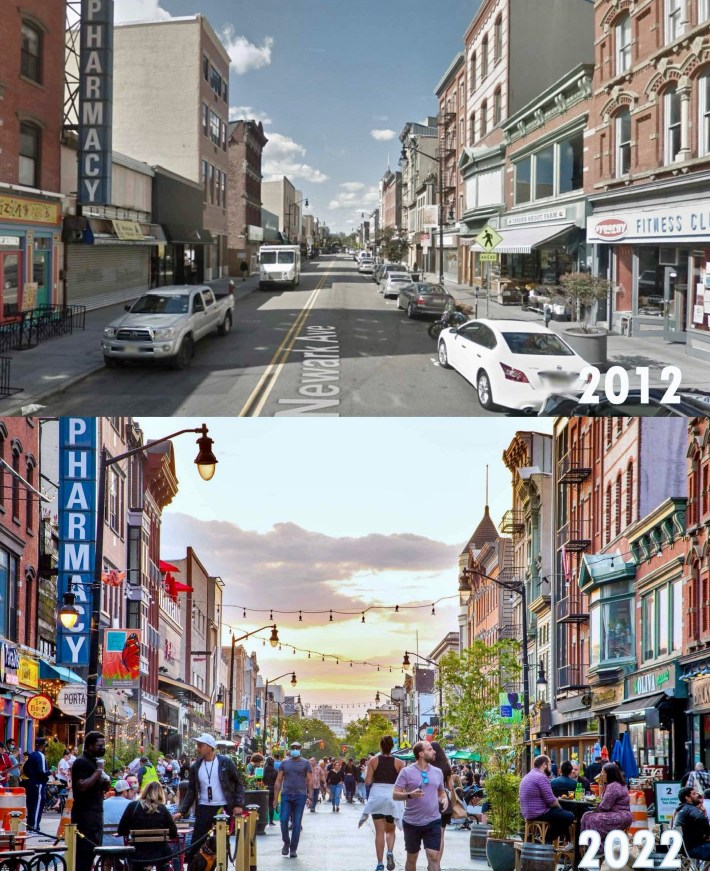

The city also closed off a section of Newark Avenue and created a car-free pedestrian mall.

Fast fixes, hard infrastructure

Key to Patel's approach was "tactical urbanism," a practice of quickly deploying low-cost protected bike lanes or corner curb extensions, before building them out with hard barriers and planters.

“The city is a lab, we should be trying different things, and we should be iterating on the things that work," she said.

Some of the bicycle paths rival those in European bike capitals, like the Copenhagen-style raised two-way bike lane along an extended sidewalk on Coles Street, a key north-south artery which connects Jersey City to Hoboken.

The city also pioneered safe intersections — which are usually the most dangerous part of a street — by installing concrete buffers at corners like Grove and Grand Streets.

By contrast, New York City too often relies on flimsy plastic and paint, and capital buildouts can take more than a decade.

Jersey City also rolled out secure storage and battery charging kiosks, something New York City has struggled to do at scale.

The New Jersey city does not have control over its mass transit service, with its buses and light rail run by NJ Transit, and PATH trains to Manhattan operated by the bi-state Port Authority — not unlike New York City, where the state's Metropolitan Transportation Authority operates the subways and buses.

To connect people in more transit-starved parts of the city like its southern end, the city contracted the company Via to create an on-demand micro-transit service, whose purple vans transport residents via an app starting at $2.

Patel's infrastructure work has changed people's lives in all kinds of ways. Morgen, who used to live in Hoboken before moving to Jersey City, met her now-husband on one of the paths installed under Patel's tenure.

"[Patel] managed to implement low cost traffic calming counter measures, in addition to some projects that were not low cost and made a tremendous difference," said Emmanuelle Morgen, executive director of Hudson County Safe Streets. "It’s because of those bike lanes that I took up biking and I met my partner on a group bike ride. I’m so grateful for her service and I probably wouldn’t have met my husband if it hadn’t been for her bike lanes."