Better bus service is coming to a portion of Flatbush Avenue ... eventually.

The Department of Transportation announced on Friday that workers will "begin installing" center-running bus lanes on Brooklyn's diagonal spine between Livingston Street and Fourth Avenue — but buses won't start moving as fast as they could on the stretch between Fourth Avenue and Grand Army Plaza until the fall of 2026, more than full four years after the city first did outreach for the project.

The full plan which includes pedestrian bump-outs and bus boarding islands will have to wait until the spring, officials said. But on the plus side, the short stretch between Livingston Street and Fourth Avenue will be an active bus lane this fall, DOT said.

Adams tries to clean up his record on bus lanes

The Flatbush Avenue project sat more or less on the shelf at DOT after it first conducted outreach for potential bus lanes on the corridor back in 2022, Adams's first year in office, when Hizzoner did show up on Flatbush Avenue to tout his plans to build 150 miles of bus lanes in his first term.

He didn't come close.

Beyond routinely sabotaging DOT bus priority projects in Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx, Adams has gone as far as suggesting gentrifiers and newcomers are the ones who wanted the Flatbush Avenue bus lane rather than longtime Brooklyn residents.

The project to speed buses on a small stretch of Flatbush Avenue will be just the second bus lane that Adams, the former Brooklyn borough president, has installed as mayor in his home borough, after the Livingston Street busway went in in 2024.

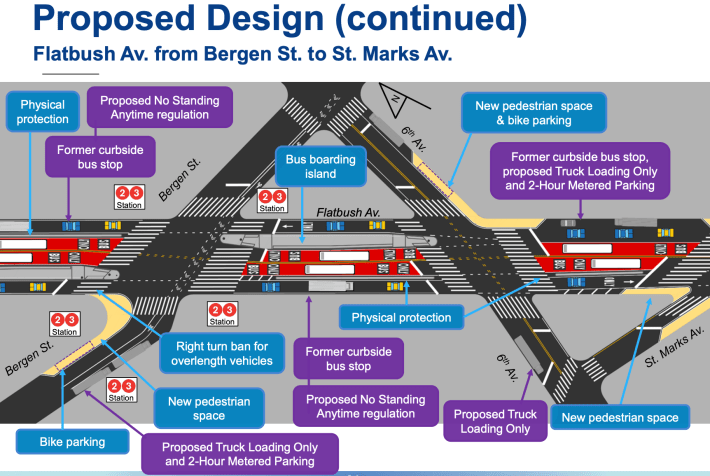

The bones of the project remain the same from when the DOT unvield details early last month:

Flatbush Avenue will eventually get center-running bus lanes between Grand Army Plaza and Livingston Street, and the city will build concrete bus boarding islands in the median so the bus never has to pull out of the red paint to pick up and drop off riders.

The design is undoubtedly ambitious. It will cut most of Flatbush Avenue down to one general travel lane in most places and expand pedestrian space and bike parking along the corridor in hopes of finally making Flatbush Avenue feel more like a neighborhood street. Curbside parking will become travel lanes along most of the street, or become restricted to two-hour parking or loading zones where it remains.

But the design also has problems, according to international bus rapid transit experts Annie Weinstock and Walter Hook. Those include the fact that the northbound bus lane ends shortly before a left turn from Flatbush Avenue onto Livingston Street, which will put buses in a traffic queue with general traffic there. The pair specifically called out that pinch point in a recent analysis of the plan, noting that "buses today often get stuck trying to make the northbound left onto Livingston. ... Because this shared lane frequently backs up ... it sometimes takes more than one signal cycle for the buses and mixed traffic to make the left turn, causing a major bottleneck on Flatbush."

The design also keeps a left turn from Flatbush Avenue onto Lafayette Avenue, which at the very least forces buses to wait for a separate phased left turn signal and could slow down northbound buses at that location if drivers get stuck in the intersection when the light changes.

The pair also made that rarest of suggestions from bus planning types to actually keep some roadway capacity for cars and trucks by finding a way to keep a second southbound traffic lane on Flatbush between State Street and Atlantic Avenue. As they explained in their critique of the plan, the right turn bay at Flatbush and Fourth "frequently backs up because the block between Flatbush and Atlantic is extremely short, and many trucks are making this turn."

As such, they suggested narrowing the lanes slightly and taking some sidewalk space from the relatively underused sidewalk on Flatbush by the Apple Store and restoring that space on the Ashland Place side to balance things out and possibly avoid big traffic queues on the southbound side.

Weinstock suggested that the center-running bus lane proposal had a lot of potential to be a great bus rapid transit showcase if done right, but also said she was worried that if the DOT made a series of radical changes but didn't execute it well, it could leave the push for BRT worse off.

"If they do it the way they've designed, it's both a potential disaster and a missed opportunity," she told Streetsblog.

DOT's commencement of part of the project could, at least, give the mayor a last-minute election-year win after this administration has fallen so short in meeting the mayor's promise of at least 37.5 miles per year.

That poor record makes it more egregious that, on Friday afternoon — right after DOT's announcement — the mayor's official re-election account on Instagram posted an infographic that said Adams is "backing 150 miles of new and enhanced bus lanes" across the city.

In other words, the same promise from four years ago.