This plan is all right ... except for a few lefts.

The Department of Transportation's bus-first transformation of Flatbush Avenue is an ambitious project that could speed buses by 20 percent while also calming the roadway's notorious traffic. But a couple key pinch points on the north end of it could also doom the project, one expert told Streetsblog.

First, the basics

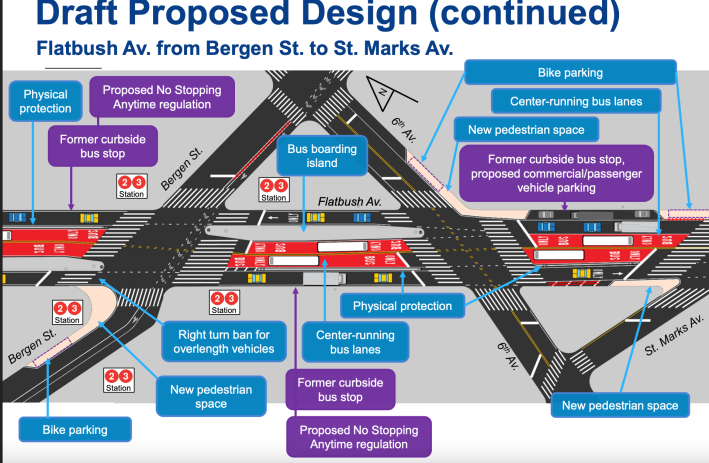

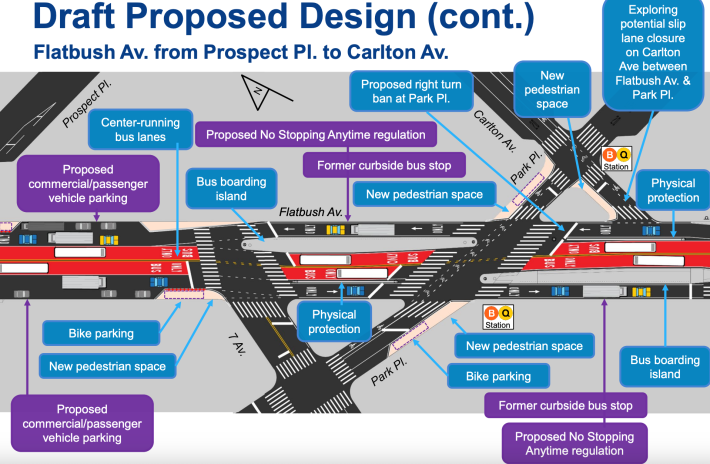

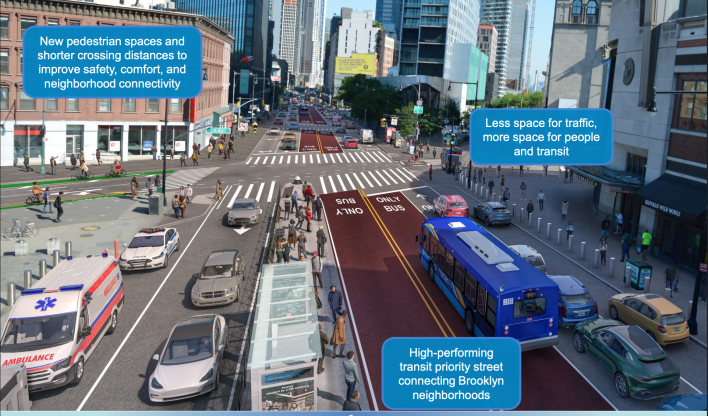

DOT's proposal for bus lanes for Flatbush Avenue between Grand Army Plaza and Livingston Street [PDF], would reduce three travel lanes down to one on each side of center-running north- and southbound bus lanes complemented by concrete bus boarding islands for most of the project area.

Buses serving 132,000 people per day on 12 bus routes are bogged down in traffic that makes their average speed just 4 miles per hour on parts of their runs.

But the plan, which will be presented to local community boards this fall, gives buses a clear runway thanks to physically protected lanes on the commercial stretch. The result would be a rebalancing of space from car drivers, most of whom are merely through traffic, to the business-friendly users of that area: the 92 percent of people who get to Flatbush Avenue by walking or public transit, according to DOT.

Curbside parking would be taken away from huge stretches of the avenue south of Atlantic Avenue, with the additions of loading zones and more than 14,000 square feet of painted sidewalk extensions. The draft plan adds 170 bike parking spots on 14 new bike parking areas and will potentially even close a slip lane from northbound Flatbush to northbound Carlton Avenue to make the road safer for pedestrians.

And safety is a key part of this proposal; the DOT says that 140 people have been killed or severely injured in the last five years on this Vision Zero Priority Corridor. The raw numbers are even more alarming: Over the last five years on just the 1.15-mile stretch between Grand Army Plaza and Livingston Street, there have been 1,143 reported crashes injuring 596 people, including 78 cyclists and 89 pedestrians, according to NYPD stats.

Moving stops to the median in Downtown Brooklyn especially will do wonders for the bus, as a team of Streetsblog reporters discovered on Friday as they rode the B41 between Livingston Street and Grand Army Plaza. The biggest chokepoint on the route was at the intersection of Flatbush, Fourth and Atlantic avenues, where traffic and illegally parked dollar vans prevented buses from making smooth pickups and drop offs and often had to stop in the middle of the street to let people on and off.

Bus riders said they were encouraged by the changes because they are sick of being ignored by generations of leaders and their evaporating promises of better service on the corridor.

“Politicans? They couldn't care less,” said rider Fernando Reyes.

Rita Clarence said the B41 is "no good!"

"I live past Church Avenue, and sometimes it’ll take me 45 minutes just to get downtown,” she said. "It's very important to me because I'm not a driver. I need the bus."

An expert speaks

The median bus stops will help avoid the pinch point, but the design north of Atlantic Avenue is where the city should make some tweaks in order to prevent general traffic and bus traffic from getting stuck in the muck in Downtown Brooklyn, said international bus planning expert Annie Weinstock, who argued for the center-running option almost a year ago.

One tweak: only allow buses to make the left turn from northbound Flatbush Avenue to Livingston Street, which itself has a two-way busway and one-way general traffic street.

"They should close that block of Livingston Street to [cars] altogether," Weinstock said. "There are other ways to get to Livingston Street, and that one block [between Flatbush and Nevins Street] is not such a destination."

Another tweak: The DOT should also ban left turns from southbound Flatbush Avenue to Lafayette Avenue, Weinstock said, because traffic often backs up there — traffic that could spill into the bus lane. Plus, any vehicles stuck in the intersection when the light changes could slow down northbound buses.

Drivers have other ways to access Lafayette, she added.

"There's an alternate routing that can pretty easily get people to where they want to go without maintaining that left turn, which is going to cause a lot of a lot of additional delay," she said.

Looking even more granularly, Weinstock said that the city should create a much longer bus loading platform through the intersection of Fourth Avenue and Flatbush Avenue because only the only turn off of Flatbush at that intersection is for right-turning cars onto Fourth. The current draft plan (above) leaves a heap of empty asphalt that's basically wasted space that could be used for bus boarding, queuing or streetscape improvements at what is now a hellscape.

"Extend[ing] the that station all the way through the intersection ... would make more space for buses," said Weinstock. "It's dead space, and they can extend that all the way through the intersection and allow more space for people to wait and for buses to stop or queue."

In an eyebrow-raising argument that you usually won't hear from bus planners, Weinstock also argued that the DOT should add a second general travel lane back to sections of the street approaching Fourth Avenue and between Atlantic Avenue and Fourth Avenue because Flatbush lacks parallel streets — and the types of vehicles using Flatbush are less able to change their routes.

"Fourteenth Street has a lot of parallel streets [but] Flatbush Avenue doesn't, it's a diagonal is serving a pretty critical traffic function," Weinstock said, referring to how traffic more or less disappeared after the 14th Street busway was installed.

"There are a lot of trucks on Flatbush, especially north of Atlantic. And so it's not quite the same situation, that they would just choose not to travel."

Weinstock pointed out that even in the DOT's own renderings of the project, the sidewalk next to the Times Plaza between 4th Avenue and Atlantic Avenue has a police car parked in it despite the fact that it's supposed to be a No Standing zone, indicating the city already expects people not to respect the regulation. In that case, she said, the DOT might as well shave off some of the pedestrian bump outs and let cars and trucks just drive there.

The tweaks seem minor, but Weinstock insisted that the city needs to get this right because the very future of real bus rapid transit hangs in the balance.

"Building BRT down the center of Flatbush Avenue is like performing open-heart surgery – DOT should assemble a team of the best surgeons in the world. They only have one chance to get this right or they risk killing the concept of BRT forever," she said.

Additional reporting by Yoshi Omi-Jarrett and Matthew Sage