Welcome to part two of the 2016 NYC Streetsies (catch up on part one here).

The alternate headline of this installment is: "Andrew Cuomo doesn't deserve an ounce of credit for improving New York City transit."

Transit Travesty of 2016

In a few days, Andrew Cuomo will ring in the new year with a soiree celebrating the debut of the Second Avenue Subway. It will be hard for transit advocates not to gag.

Cuomo has spent his entire six years in office putting off the hard work of fixing the many systemic problems that confront New York City's transit system. His record runs more toward indulging in vanity projects and robbing transit riders via the state budget.

There's something grotesque about this political figure claiming credit for the city's most anticipated transit expansion project in 75 years. He wasn't involved in getting phase one of the Second Avenue Subway into the construction pipeline -- Mario Cuomo, George Pataki, Eliot Spitzer, and other assorted politicos got the project past the point of no return before Andrew took office. His main contribution was his determination, verging on recklessness, to avoid the embarrassment of opening the new line a few months into 2017.

But it's also fitting that Cuomo happens to be in charge at this moment. For several years now, he's managed to project an image of accomplishment while letting the key reforms necessary for lasting transit improvements go unaddressed. The opening of the Second Avenue Subway is the culmination of this dynamic.

To counterprogram Cuomo's stage-managed pomp, we offer this year-in-review post looking back at how he has repeatedly failed to represent the interests of transit riders.

The cost problem

There's a reason New York has wanted to build another East Side subway for nearly a hundred years. Though the first phase of the Second Avenue Subway adds only three stops on the Upper East Side, it's expected to fill with passengers instantaneously. Some of the projected 200,000 weekday riders will be siphoned from the parallel Lexington line, relieving crowding and improving reliability on the most overloaded trains in the system.

New York could use more projects like this -- not just in future expansions of the Second Avenue line but also along densely developed stretches that lack good subway access in other boroughs. Added subway capacity will make room for much-needed housing. To build more subways, however, the MTA needs to get its construction costs under control. Here's where Cuomo could have made himself useful, but didn't.

When Cuomo was elected in 2010, the high price tag of the Second Avenue Subway was already an embarrassment. At $1.7 billion per kilometer, it will be by far the most expensive subway project in the world (until it's eclipsed by the MTA's East Side Access project).

And yet, in six years as governor, Cuomo has done nothing to bring the MTA's construction costs in line with global norms. There have been no state inquiries or reports attempting to isolate the causes of excessive costs and identify solutions. Not even a public acknowledgment from the governor that high costs are a problem that needs to be addressed.

As the MTA turns its attention to phase two of the Second Avenue Subway, the cost problem looms larger. A preliminary construction estimate of $6 billion was released earlier this month, making it even more expensive, per kilometer, than phase one. And with ridership projected at 100,000 weekday passengers, it's a lot harder to justify the cost.

Cuomo could have secured a legacy as the governor who enabled a whole new generation of subway expansion. Instead, if he doesn't get the MTA's cost problem under control, he'll go down as the one who let New York City's subway renaissance sputter and die.

The bus problem

New Yorkers make more than two million bus trips each weekday, but that number is falling. The MTA's buses move slower today than they did five years ago, and since 2002, bus ridership has dropped 16 percent.

Transit advocates recognize the urgency of the situation, and this year they put out a detailed multi-point plan to turn around a flagging bus system. The MTA proceeded to respond in defensive fashion, brushing off the recommendations.

The debate over modernizing fare collection for buses typified the MTA's attitude. Advocates called on the agency to swiftly adopt a system known as electronic proof-of-payment, which speeds up buses by letting riders board at any door and pay without dipping a farecard one by one. But the MTA refused to commit, citing "the threat of fare evasion." Meanwhile, London, San Francisco, and other cities have used systems like this for years -- their transit officials say that getting over the fear of fare evasion opens up possibilities to provide better service.

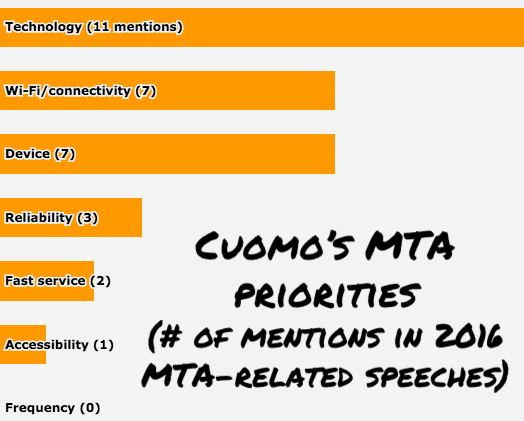

Where was Cuomo? The only time the governor was spotted on a bus this year came during a photo-op where he hyped bells and whistles like USB ports for riders to charge their devices. But New Yorkers aren't abandoning buses because they can't charge their phones on board -- they're abandoning buses because buses are slow and you never know when the next one will arrive.

That's the Cuomo approach to transit policy in a nutshell: Grab attention for a superficial upgrade by bragging about "boldness and ambition," obscuring the fact that the risk-averse MTA is stonewalling changes that could tangibly improve trips for millions of bus riders each day.

The debt problem

The MTA spends more than $2 billion annually, or over 17 percent of its operating budget, to service its debt. It wasn't always this bad -- if MTA debt returned to 2004 levels, the agency would have close to a billion dollars each year that could go toward running trains and buses instead of paying back creditors.

To reduce the MTA's debt burden, Albany needs to rely less on borrowing to fund the agency's capital program. The "bold and ambitious" thing to do would be to direct revenue from a congestion-busting toll reform plan like Move NY to the MTA, but Cuomo has never had the stomach for tolling bridges.

Still, last October Cuomo pledged to plug a $7.3 billion hole in the five-year MTA capital plan with state funds, giving everyone the impression that he would avoid borrowing that amount. Then in the beginning of the year, the governor walked back the promise without admitting that he was breaking his word.

Instead of funding the capital program without new debt, Cuomo's budget continued to rely on borrowing, with no guarantee of direct state support for transit. Making matters worse, the governor did manage to scrounge up state funds for transportation, but only for roads and bridges, which are in line to get nearly $14 billion in subsidies over five years. (This discrepancy earned the Streetsblog people's choice vote for transit travesty of 2016.)

Borrowing billions for the MTA basically guarantees higher fare hikes for millions of NYC transit riders in the years ahead. Remember that when you see Cuomo cut the ribbon on the Second Avenue Subway this weekend.