If the next mayor wants to harvest more housing, all he needs to do is pick up Streetsblog's SCYTHE.

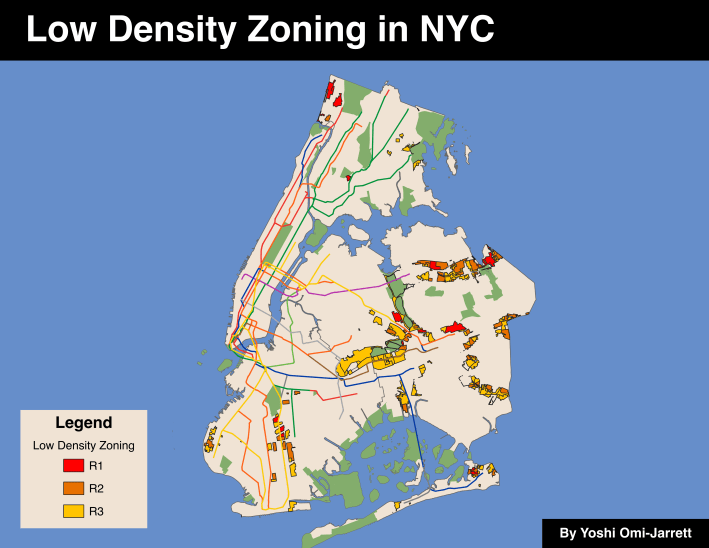

The Adams administration's City of Yes zoning change, which took effect late last year, unshackled developers from parking mandates, and allowed for taller buildings near transit-rich parts of the city. But it wasn't perfect; in a last-minute deal, the change was watered-down to prevent growth in some of the lowest-density areas, despite their proximity to transit:

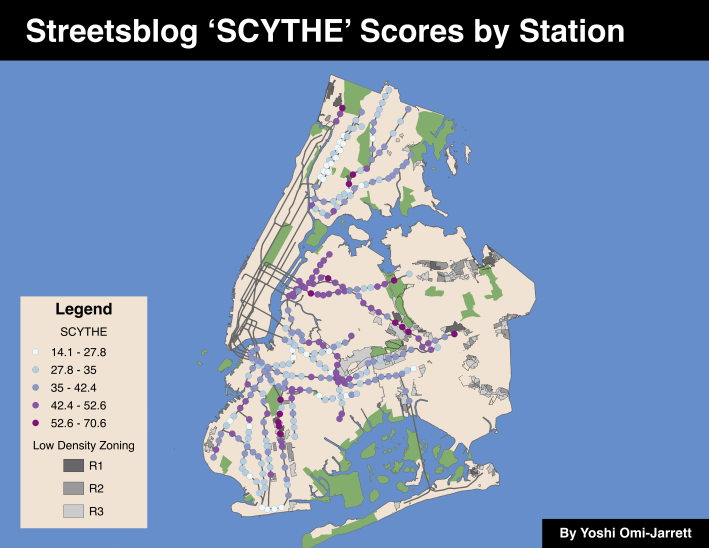

And that's where SCYTHE — or Streetsblog's City of Yes Transit and Housing Evaluation — comes in.

Streetsblog analyzed the potential for transit-oriented development at outer borough stations ripe for increased neighborhood density. Our SCYTHE ranking is based on three main factors: the number of people living near a station, the subway travel time to Times Sq-42 St, and the presence of low-density zoning near the station. Each factor is weighted equally and scored out of 100.

Here is how we did it:

- First, stations serving lower populations rank higher. Because the subway moves people much more efficiently than personal vehicles, we should encourage neighborhoods near subway stations to take on more density to reduce congestion and crashes on the city's roads.

- Second, stations with shorter travel times to Midtown rank higher. Creating housing that is far away from job centers forces people to choose between affordability and convenience. We should choose to build in places where people won’t have extreme commutes.

- Third, stations near the lowest-density zoning (R1, R2, and R3) rank higher. Much of the city’s recent housing constriction has occurred in formerly industrial sites, raising health concerns and forcing people to live in undeveloped neighborhoods with inadequate residential amenities. By building in neighborhoods with existing low-density housing, the city is more likely encouraging people to live in places that are already nice areas to live.

Why SCYTHE?

This type of approach to development is possible because of City of Yes, which reduced parking mandates and softened height restrictions in areas near transit and along commercial corridors. By making it easier for developers to build larger apartment buildings in places where people won't be reliant on cars, the city can foster walkable communities and livable streets.

New York City’s high rents stem from inadequate housing supply, which experts attribute in part to restrictive zoning rules that limit the number of units built in new apartment buildings. Parking mandates also force developers to build expensive car storage, though City of Yes eliminated them near transit.

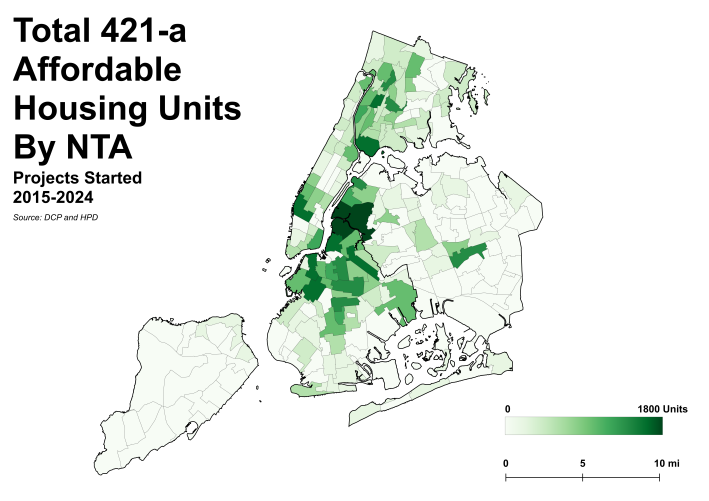

Most of the city's newest housing is concentrated in only a few neighborhoods, like Williamsburg and Long Island City, putting extreme pressure on those areas to bear the weight of the city’s lack of housing. Affordable housing programs, such as 421-a, have done little to encourage housing construction outside of north Brooklyn and western Queens:

One of the main objectives of the City of Yes is to induce more housing in low and medium density neighborhoods by allowing for modest apartment buildings and accessory dwelling units, which are small, independent residences in the backyard or basement of a single-family home. Many of the areas identified by SCYTHE are places perfect for those so-called "granny flats."

The allowances for three-story to five-story apartment buildings are focused in areas near rail transit in order to spur transit-oriented development. Unfortunately, the City Council altered the original plan in the last hour, nixing areas zoned for single-family housing from the transit oriented development accommodations.

SCYTHE in action

Here is the list of the top 10 stations:

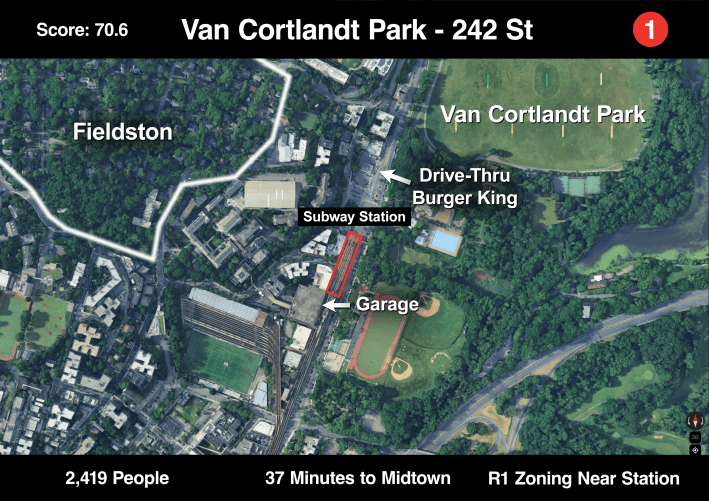

1. Van Cortlandt Park - 242 Street

This station has the lowest nearby population (2,419) of any station in this list, partly because of the geography of the area: Van Cortlandt Park is to the east and there are steep hills to the west. Right around the station, though, are low-density commercial buildings and a large garage. Just up the hill is the privately owned, suburban neighborhood of Fieldston — which contributes very little to the density of the neighborhood — although it's probably impossible to change that due to its status as a historic district.

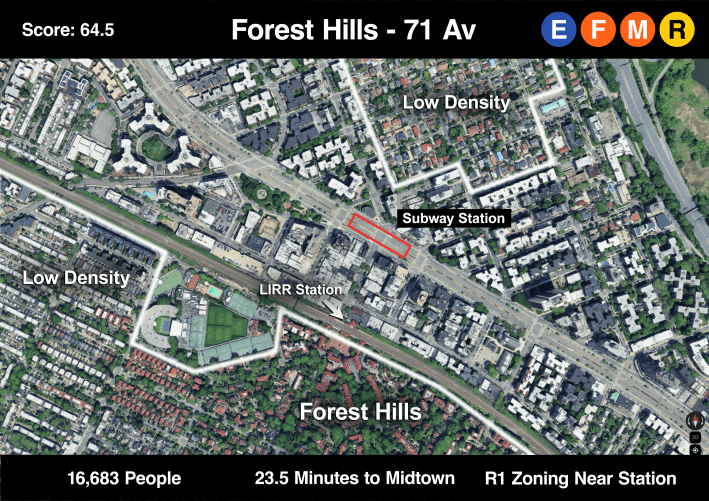

2. Forest Hills - 71 Avenue

Forest Hills is a unique neighborhood with its uniform Tudor architecture. But with four subway lines and a Long Island Rail Road stop, the neighborhood can fit many more people. Again, building housing here would be nearly impossible as the neighborhood is considered a historic district (and you know what that means: hotly contested public housing project). But a neighborhood's history of race-based anti-housing activism shouldn't stop the city from finding some other way to increase the density around this station.

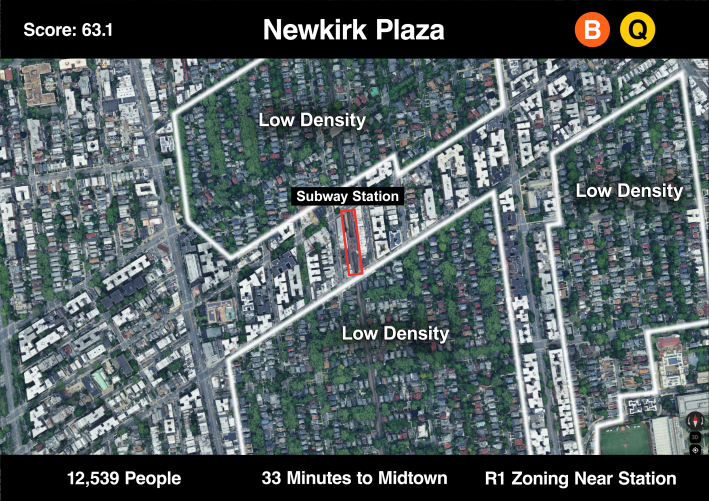

3. Newkirk Plaza

Newkirk Plaza is the first of several stations on this list along the B and Q line in Brooklyn. The Ditmas Park community is mostly comprised of single-family homes with driveways and front lawns. It's not ideal for the city to have a neighborhood this lightly populated that's only 30 minutes by train to Midtown.

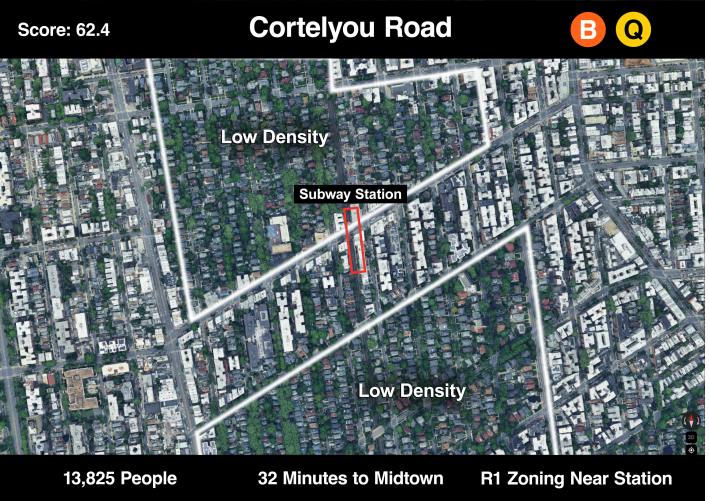

4. Cortelyou Road

Neighborhoods to the east and west have more density, but Ditmas Park underutilizes the subway corridor despite the area's easy access to Downtown Brooklyn and Manhattan. As stated earlier, a last-minute change to the City of Yes removed allowances for modest apartment buildings in single-family (R1) zoning. Still, the commercial blocks between these zones can and should be built on.

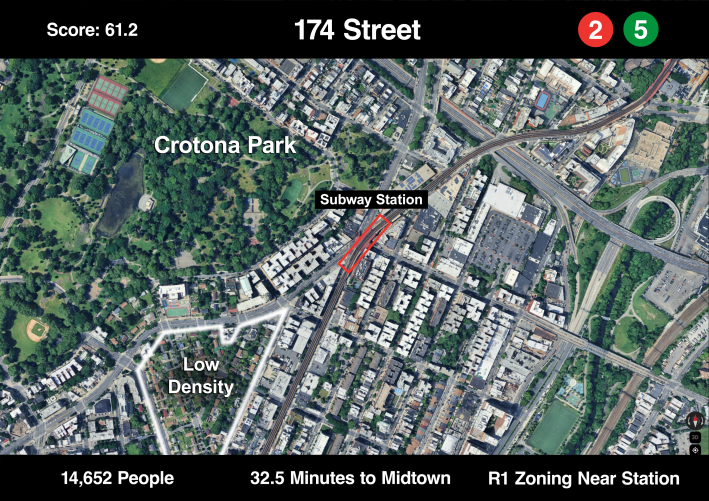

5. 174 Street

In the Bronx, the Charlotte Gardens neighborhood (in the bottom left of the photo), leaves more housing density on the table for the nearby station. Most of this part of the Bronx is dense, but places like this near parks and with quality transit access can still take on more residential development.

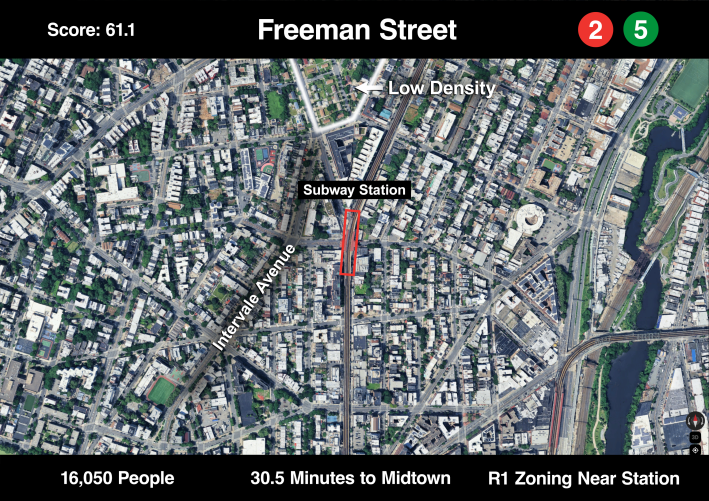

6. Freeman Street

The Freeman Street station has a similar story to 174th Street above. Intervale Avenue on the left is a residential street with some three-story apartment buildings, but also many small duplexes with driveways. There is no good reason more people can't live on streets like these that are just feet from a subway station.

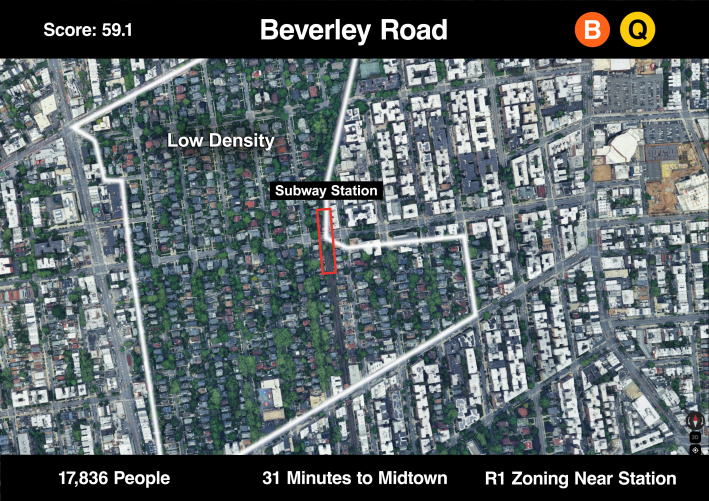

7. Beverley Road

Back in Ditmas Park, the outlined area in the photo below shows how many low-density, tree-lined streets are near this subway stop compared to the white-roofed apartment buildings in the denser northeast. More apartment buildings near this station would be good for the rest of the city's renters.

8. Church Av

As the subway gets closer to Prospect Park, the inclusion of park-space inflates the score of this station. There is also still lots of nearby low-density housing, but in a city that often lacks park space, we should be looking to build more homes near the parks that already exist.

9. Prospect Park

Just to be clear, we are not calling to develop housing in the park. But, the adjacent Prospect Lefferts Gardens neighborhood could do so (they have a track record of restricting development). This is certainly not the lowest-density neighborhood in the city, but the nearby R2 zoning shows that there is room for growth.

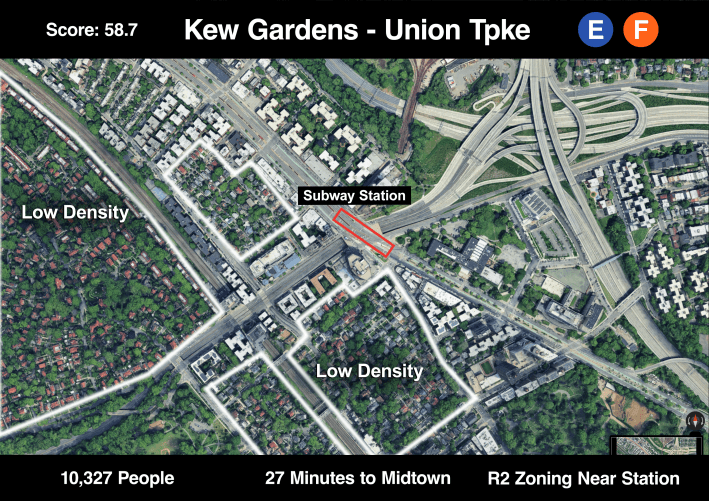

10. Kew Gardens - Union Turnpike

The Kew Gardens station shows up on this list because of the massive highway interchange to the northeast and because of the low density housing to the south and west of the station. Perhaps the Jackie Robinson Parkway, which runs under Queens Boulevard, could be capped and replaced with some apartment buildings.

(Note: Population data for this analysis was sourced from the American Community Survey (2019-2023 five-year estimates), and travel time data from MTA's GFTS database.)

Limitations

One limitation of SCYTHE is that stations near parks will rank higher even if they are relatively dense, as the station population catchment area doesn’t account for the types of uses near a station. This could be framed as a case for relatively higher densities near parks, as much of the city’s population lives in places without enough greenspace.

Another potential limitation is that a station’s proximity to low density zoning inflates the score of a station. Stations near single-family zoning (R1) will be weighted significantly higher than a station without, even if the other characteristics are better. This emphasizes the need to build in neighborhoods other than those that are currently gentrifying, like Bushwick and Astoria.

We also chose to focus on Brooklyn, Queens, and The Bronx for this analysis. Manhattan would dominate the list because of the density of many neighborhoods and proximity to Times Square. For context, the station with the largest population is 72nd Street on the 1, 2, and 3 trains with 33,528 people living in the catchment area. This station is also less than five minutes from Times Square by subway. Staten Island's complicated transportation system also makes it hard to compare to subway commutes as every trip to Manhattan either requires a ferry or an express bus ride.

And SCYTHE only takes into account subway stations, not Metro-North or LIRR stations, where density (such as at some of the eastern Queens stations) is low and travel times to Midtown Manhattan are short. Perhaps a future SCYTHE analysis will harvest that housing.

And then there's the ultimate limitation of any analysis of housing: Virtually all residential development in this city provokes community opposition — and several of the neighborhoods identified in this report have a long history of resisting development.

But City of Yes was passed in order to force these and other communities to take on their fair share of density.