It's a transit-oriented debacle.

When it approved Mayor Adams's sweeping rezoning proposal last week, the City Council modified the plan so that it now spares single-family districts from accommodating small apartment buildings near transit or in commercial zones — a move that will result in thousands of fewer new units of housing and an unconscionable capitulation to lawmakers from "suburban"-type districts, experts said.

The City of Yes for Housing Opportunity, which is poised for expected passage by the full Council next month, sought to re-legalize a common housing type that long existed in low-density neighborhoods, but that has been illegal to build since the last time the zoning code was overhauled in 1961.

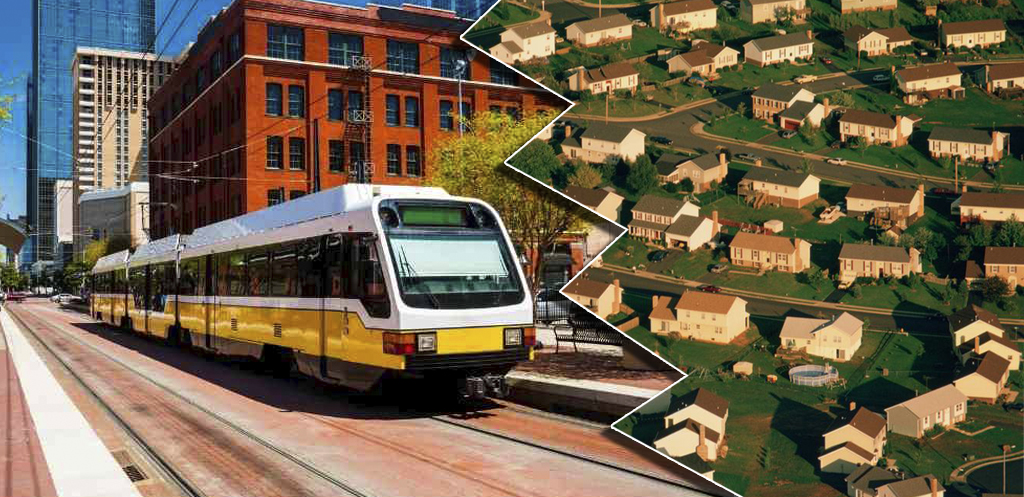

Think three- to five- story apartment buildings near transit, or on commercial strips with ground floor retail and apartments above it. The City of Yes proposal for such “transit oriented development” and “town center zoning” would have given developers a bonus to build up to three, four or five stories, depending on the underlying zoning district, as long as they were within half a mile of rail service or in a commercial zone with ground-floor retail.

That bonus remained in the final version — except the Council eliminated it from areas that are zoned single-family, giving in to pressure from politicians in Queens and Staten Island who rallied to protect their “suburban” way of life.

The single-family two-step

Experts and housing advocates are more or less pleased with the final City of Yes plan, but decried the single-family zone exemption because it means that no three-story apartment buildings will be built within half a mile of the Long Island Rail Road in Eastern Queens, for example, even though such housing had been a mainstay three generations ago. The change was hailed by lawmakers in those neighborhoods, but it is a change that will result in few units being built near transit, units whose residents could be far less car-dependent.

“The exemption from the ‘transit oriented development’ bonus for single-family districts will have the greatest effect on the mid-density category of buildings, like modest multi-family buildings,” said Marcel Negret, the director of land use at Regional Plan Association, whose report, City of Yes and Missing Middle Housing, analyzed how such small multifamily buildings have gone extinct and how the plan was trying to bring them back. “And for ‘town center zoning,' they're exempting from the bonus areas where the commercial overlay is in a block that is predominantly single- and two-family. That also takes away a good chunk from that mid-tier category.”

Winners and losers

Single-family zoning is only 15 percent of the residential area of New York City, but residents came out in force during the public review process to oppose middle-density building — and it worked.

During the Planning Commission’s 15-hour public hearing, a Queens resident called for secession from New York City if the City of Yes passed. Another resident said the proposal “is attempting to transform our suburban areas into high-density zones.” [It was not.] And another Queens civic association leader said transit-oriented development “isn’t fair” to single-family homeowners.

The two Council members who voted in their subcommittee against the modified proposal, David Carr and Kamillah Hanks of Staten Island, represent large swaths of single family New York.

Carr's public comments suggest that he believes sprawl and car dependence are essential factors of quality urban living.

“You know, I come from a community that is home to people who chose to leave where they came from, usually other parts of the city, in order to find a better quality of life,” said Carr when explaining his “no” vote.

This idea that single-family zoning must be protected at all costs influenced the Council’s decision to exempt those districts from most of the proposal.

"One-family zoned districts represent less than 15 percent of the city's land area, and they are scattered in small areas throughout the city," said Council Member Kevin Riley, chair of the Zoning Subcommittee last week. "They are valuable ... in terms of maintaining the diversity of housing choices for New Yorkers. For some households, having access to a yard, a garage and open piece of land is an important role, and we do not want to drive away these New Yorkers."

Experts said that allowing single-family areas to opt out of modest proposals like “transit oriented development” doesn’t make sense.

“It’s clear that most of the modifications affect the low-rise districts, so I think that the high-rise districts are pulling more weight than the low-rise districts [in siting new housing],” said Moses Gates, the vice president of housing and neighborhood planning at the Regional Plan Association. “In the single-family zones, it’s borderline whether they're going to be doing more [than currently], but everybody else is. [Exempting single-family from transit oriented development] makes the least sense from a planning perspective.”