The city's hugely-popular car-free Open Streets program shrank over the last four years and remains concentrated in Manhattan, according to a new report by Comptroller (and mayoral candidate) Brad Lander, who called on the city to invest more in the ailing pandemic-era initiative.

The largely volunteer-run program's already inadequate funding threatens to run dry, Streetsblog previously reported. Its retreat mirrors a similar trend with the Covid expansion and contraction of outdoor dining.

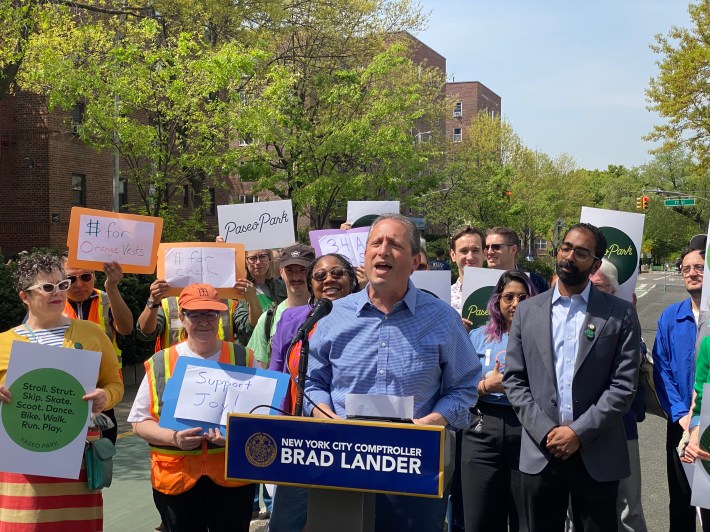

"People realized we needed new places to be outside, unfortunately we have not… provided resources for that work to continue," Lander said at a press conference on Friday at the 26-block "gold standard" 34th Avenue open street in Jackson Heights, also known as Paseo Park.

"Volunteer groups cannot sustain the work to successfully operate open streets without more resources, support, and clear guidelines from the city," Lander added. "At a time when City Hall's lukewarm support could close the Open Streets program, let’s expand it, let’s support it, let’s help resolve conflict when it arises – and let’s make public space available to all."

The total number open street locations hit a low in 2023, but trended back up last year after a $30 million funding boost by the Department of Transportation, which runs the program. That funding came from federal Covid money, which has since run out. Mayor Adams appears uninterested in replacing the cashflow from Washington, D.C.

At the same time, the average number of open streets has dropped from a peak of 326 sites in 2021 to 232 in 2024, according numbers by DOT, which Lander's office crunched across the program's first four years. This spring, 127 open street locations will roll out, according to DOT — though the agency expects more to come online throughout the year.

The average length of city open streets dropped by nearly a third (32 percent) between its peak in 2020 and 2024, and operating hours per week fell by 40 percent, according to the comptroller's analysis.

Meanwhile, wealthy Manhattan maintained the largest share of the open streets pie every year, with 87 locations last year — more than Queens (45), the Bronx (29) and Staten Island (6) combined. Brooklyn had the second-most car-free streets at 67 locations.

Lander's report includes a list of recommendations to improve open streets.

The city should bring the program to every neighborhood, and baseline reliable public funding, according to the comptroller. He also wants to make it easier for the volunteer groups to apply and to get paid, and urged the city to track use, economic impact and progress toward pedestrianizing the temporary closures.

The downward trends of the open streets over four years confirm Streetsblog's extensive reporting on the steady rollback of operating days and hours across the city.

Many of the once-booming car-free corridors cut their hours under the Adams administration, such as Brooklyn's Vanderbilt Avenue, Fifth Avenue, Willoughby Avenue and South Portland Avenue.

In Manhattan, the Canal Open Street also reduced its days and hours, however primarily due to a backlash from a handful of upset neighbors.

The Fifth Avenue Holiday Open Street in Midtown scaled back last winter, despite Mayor Adams touting it as a boon to bottom lines just the year before.

Nonprofits and other community groups also waited years for DOT to pay them back, meaning many were forced to front tens of thousands of dollars to keep going.

"Currently there’s a pittance of money that the Department of Transportation gives us, and that money we get paid for about one or two years after we submit receipts," said Nuala O’Doherty-Naranjo, who co-founded the 34th Avenue open street. "We’re talking about money for chalk, money for a Zumba class, money for Legos, money for programming that brings people together."

The city should dedicate funding and staff for the open streets, especially the setup, managing, and takedown of the barriers, said an organizer behind the Vanderbilt open street.

"That’s the biggest operational cost," said Saskia Haegens, the vice chair of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Corporation. "As soon as you run more than a couple of days, you can’t staff that with volunteers. I would have to staff like 500 volunteer hours for the season — I can’t do that."

The unpaid or slowly-paid labor produced a plethora of benefits, including boosting businesses revenues and gains in street safety, Streetsblog has previously reported.

Closing off just three blocks to cars in Brownsville brought the community together from public housing complexes and a homeless shelter, breathing fresh life into a neighborhood plagued by gun violence, said the local open street's organizer.

"When we are outside and we’re able to observe, we’re able to look, we’re able to listen, we’re able to sit down... we’re saving a life," said Tyisha Jackson, the executive director of the violence intervention group Incredible Credible Messengers. "Open streets is a celebration after Covid, after the social impact that it had on our children, after watching people die."

More than a dozen open streets groups recently demanded $48 million in city funding over the next three years to shore up operations citywide for the program.

That sum is a "bargain," given the upsides from open streets, according to Lander, who is running to replace Adams.

"If you provide resources to enable open streets to happen, not only will you have a beautiful open street, but you’ll be supporting the growth of a neighborhood safety institution, [New Yorkers] would think that $48 million was a bargain," Lander said in response to a question from Streetsblog.

Lander compared staffing issues to city parks, but he said in order to have city staff working directly on open streets, City Hall would need to increase the budget of agencies like DOT and the serially-underfunded Parks Department.

"It wouldn’t work if we said, “Well, you know, we have parks, they’re there, what do you need the staff for," Lander said. "The parks staff is already quite stretched, so you’d need to have a lot more parks workers before you could ask them to also take care of open streets."

A DOT spokesperson claimed the report's year-to-year comparisons were unfair because the agency's own numbers have been wrong before. The rep cited a 2021 report by Transportation Alternatives, which found that less than half of the open streets the agency listed on its website were actually active.

"Through funding for Open Street operations and permanent redesigns of existing locations, NYC DOT has supported roughly 200 Open Streets across the five boroughs in recent years—including at a record number of schools in 2024," said Vin Barone in a statement. "In 2021, a report found the majority of Open Street locations weren’t operating as scheduled, so NYC DOT has worked to grow the program since then with a focus on consistent, reliable operations and an equitable distribution across the city."