East Side, West Side, all around the town...

A pair of international bus experts have created a method for figuring out the best places in the city to create high-speed bus rapid transit — and it sure beats the current method of guessing or simply basing the route on how strongly a given neighborhood opposes or supports it.

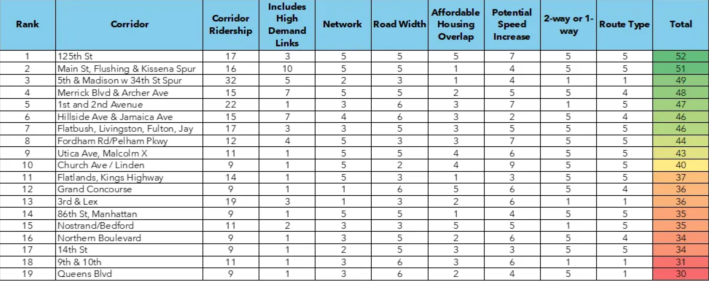

The new analysis by New York-based international bus experts Annie Weinstock and Walter Hook lays out a series of factors beyond just bus speeds that they say the city should weigh when creating BRT corridors. The city should also consider:

- the total ridership of a corridor

- whether the proposed BRT pieces connect to high-ridership bus lines

- whether the road is wide enough to include full BRT and if there are nearby roads that can handle traffic that would be rerouted off a corridor

- whether the service would help low-income populations

- whether the new service would complement existing subway service with a new rapid transit option

- the time savings from implementing bus rapid transit

- and what kind of bus routes already serve a given corridor (with a preference for Select Bus Service, limited routes or the new rush routes in Queens).

By weighing each of those factors, and doing so in a public-facing manner, the city can make a good case for where to start with BRT rather than taking a guess or basing that decision on how vocal a given neighborhood is for or against the service.

"I think this helps an administration to go into a political discussion armed with technical facts that it can respond to community input," said Hook, whose prior analysis with Weinstock examined the results of every bus priority measure that the city and MTA had introduced in the last 15 years. "This gives the administration a basis to sort of go into a community and say, 'Well, our analysis shows that what would bring the highest amount of benefit to any community in the city.' Or with electeds: 'You guys can decide you don't want this in your neighborhood, but the benefits would be gigantic.'"

A highly visible and technical analysis could also help guard against more corrupt shenanigans in the planning process.

"To insulate advocates against inappropriate political input into the decision-making process, this data will arm us with the kind of technical tools we need to question decisions that are maybe a little dubious. Otherwise, if you're what you're left with is like some crony of the mayor wants the city to dump a lot of money into a high-quality infrastructure because they happen to have a bunch of real estate developments along a particular corridor. Suddenly, that project gets elevated up to the top of the list and people ask, 'Well, why is that one on the list?'" said Hook.

So what's good?

The analysis that Weinstock and Hook put together identified 125th Street in Harlem as scoring the highest in terms of the benefits of BRT. Given that Phase Two of the Second Avenue subway isn't supposed to open until 2032, upgrading the existing crosstown service on 125th Street with physically protected bus lanes and bus boarding stations could provide subway-esque service at a fraction of the time and cost.

"That subway isn't going to be built for many, many, many years. And in all of the years we're waiting for that subway to be built, people will be stuck on the bus in traffic. So if we could build a BRT now, if it lasts for the 20 or 30 years that it takes to build that subway, that would be great. It might also be that it's serving that population so well that we'll find that a subway isn't needed there, but in any case, the need is there now," said Weinstock.

Hook added that bringing bus rapid transit to 125th also would benefit bus riders using the M60 to get to LaGuardia Airport as well as allow a few other neighborhood bus routes that serve places the subway doesn't to pick up speed moving through what is usually a congested corridor.

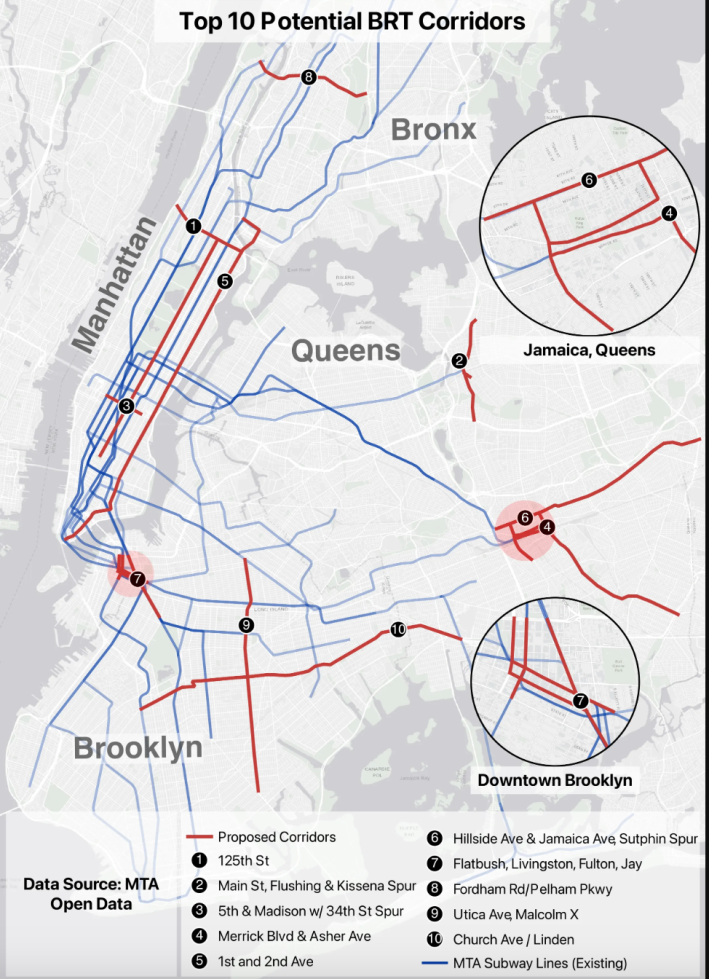

In total, Weinstock and Hook came up with 19 corridors that they think could support real-deal bus rapid transit, which is more than most cities in America have. Creating just one would of course bring huge amount of benefits to tens of thousands of bus riders, but the duo also showed off what a map (above) of what their top 10 corridors could do, a vision of bus service that could probably change the landscape of the city.

It's hard to say if the city and the MTA will be embracing international-style bus rapid transit anytime soon. Since Andrew Cuomo's version of the agency stuffed SBS into a box and put it in an attic in 2018, the MTA has not explored any aggressive bus service interventions on that scale. Doing something like BRT would also require the MTA and the city to work closely, something that has gotten more and more fraught as the Adams administration has killed more and more bus projects.

"I'm for faster buses," MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber told Streetsblog on Wednesday. "And I think that the we should definitely deploy the tools that we have and that were promised to us and that are in the law, like more bus lanes. We're always going to look at solutions that are more ambitious, obviously [this is] not funded in the capital plan, but we're going to look at the range of solutions that are available to have faster bus service. But we always start with the strategies that are actually law and policy right now, and we want to implement those and have our partners in the city help us do that."

A spokesperson for the DOT said the agency would review the report and claimed the city had been speeding up buses, though their average speed has remain mired at 8 miles per hour for seven years.