New York City's outdoor dining is reverting back to more wealthy neighborhoods in Manhattan and Brooklyn, especially for structures in the roadway, as those return on Tuesday for the first time since the pandemic-era program ended and the city banned the popular "streeteries" over the winter.

Just 33 roadway cafés are set to open in all of Queens — the city's largest borough by area and second-largest by population at 2.3 million residents — along with eight in the Bronx, and zero on Staten Island, according to a Streetsblog analysis of restaurants granted "conditional approval" by the Department of Transportation.

Manhattan, with 324 restaurants, has the majority, and Brooklyn adds another 182, but even within those two boroughs, the eateries are concentrated in wealthier areas, such as largely below 96th Street in the former and in well-heeled brownstone Brooklyn neighborhoods — a change from the pandemic era program that created a virtually new streetscape for the city.

But the end of the pandemic brought the demise of that era. The City Council's outdoor dining legislation in 2023 banned the once-pervasive street-side structures from December through March, a move that ceded thousands of spaces back to private vehicle storage and undid one of the few silver linings of the Covid-19 crisis. Mayor Adams signed off on the new regs.

Sidewalk cafés, which are allowed year-round, remain more widespread throughout the city, logging 1,809 permit requests as of Aug. 3, a city deadline when restaurants taking part in the pandemic program had to apply in order to keep their seating, however, it is unclear how many of those are still active.

As a result of unequal seasonal rules, the city is pushing too many seating setups into the already-cramped pedestrian space, activists charged, rather than repurposing a fraction of the curb that is currently home to some 3 million parking spaces (largely for free).

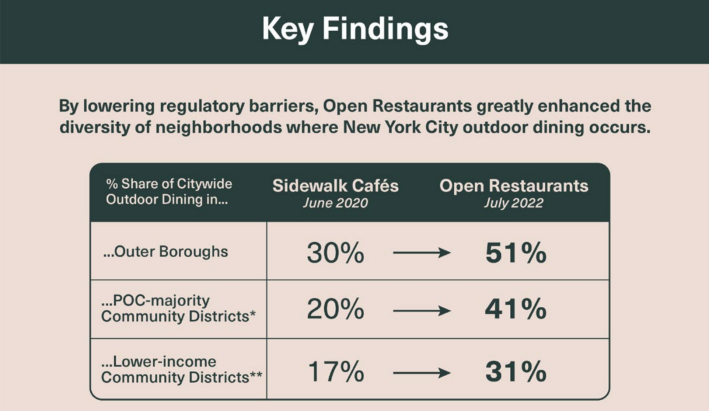

After the city loosened its outdoor dining rules during the pandemic, restaurant owners across the city repurposed the curb lane, with outdoor dining coming to 17 new community districts that never had them before under the restrictive pre-Covid licensing regime, according to a 2022 report [PDF] by New York University's Wagner School for Public Service.

"This is a regulatory nightmare," said one of the report's co-authors, Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at NYU, of the new program. "This is one of the few good things that came out of the pandemic. We’ve rediscovered that New York can make the outdoors work right."

Speaker Adams — who had said outdoor dining shouldn't be in the roadway long term during the new law's negotiations — caved to constituents opposed to roadway dining, while DOT's 31-page rules dumped too many onerous costs and regulations onto restaurants, which are largely small businesses with tight margins, according to Moss.

There are about 3,400 applications, but just 1,178 for roadway, according to DOT. That's down from a high of around 6,000-8,000 restaurants that operated at the pandemic program's peak, the agency estimates.

"They’ve made the whole thing intimidating to really what are small-scale businesses that are not well financed," Moss said. "We had a natural experiment that worked."

What's more, only seven — yes seven — establishments might be able to serve booze outside, due to the city and the State Liquor Authority not being on the same page about their approval processes.

Manhattan Assembly Member Tony Simone will propose a bill on Monday to bring back roadway dining year-round.

"While the roadway dining season officially begins on April 1, overburdensome regulations such as limiting when outdoor dining is allowed have all but killed the program in New York City," Simone's office said in a Friday advisory. "The bill will fight back against government regulations that have unintentionally diminished our streetscape and stifled small business investment in their communities."

Adams v. Adams

The administration of Mayor Adams and Council Speaker Adrienne Adams (no relation) traded jabs other over the failures to keep the outdoor dining momentum.

"City Council leadership made clear early on that they were opposed to the idea of roadway dining completely — and only through negotiation was DOT able to save the program," said DOT spokesperson Vin Barone in a statement. "The Council’s burdensome approval process for outdoor dining includes lengthy review periods and grants councilmembers the power to veto sidewalk setups, while using the same process to approve or deny a massive neighborhood rezoning to determine if a small business can place a table or chair on the sidewalk."

A Council spokesperson noted that DOT oversaw a backlog of applications and accused the agency of failing to manage the program's rollout.

"From submitting error-filled paperwork to the wrong entities to the lack of public outreach and backlog of applications, the DOT has simply failed to manage implementation appropriately, and its rulemaking has also created problems with sidewalk café and roadway dining requirements," said Council spokesperson Rendy Desamours in a statement.

"Simply pointing to the law as the source of every challenge is lazy analysis that distorts the facts about where issues are arising and going unresolved," the rep added.

Lawmakers plan to hold an oversight hearing on April 23 to find a better path forward, according to Desamours.

But the blame game between both sides of city government does little to help suffering restaurant owners and New Yorkers who just want to be able to eat outside as the weather warms again, advocates said.

"For a Council that is so focused on equity, they actually managed to reverse progress. They created an incredibly inequitable program that deprives New Yorkers all over the city of the outdoor dining they’ve come to love and rely on. This is devastating for local business and community building," said Sara Lind, co-executive director of the public policy group Open Plans (which shares a parent company with Streetsblog).

Return of the red tape

The emergency program came about when the state banned indoor dining to stem the spread of the virus, and allowed restaurants to use the curbside space for free by filling out a form, and a DOT inspector could come and check on it afterward.

The easy rules saved the industry and allowed for one of the largest transformations of the city's streetscape in recent history, and reclaiming some 8,500 car parking spots.

The emergency guidance was a far cry from the highly-restrictive pre-Covid sidewalk café licensing program, which only allowed tables and chairs on the foot path in certain neighborhoods of the city.

The new program's rules charge owners thousands of dollars in annual fees to rent the roadbed or sidewalk, and they have created a lengthy application process similar to the pre-2020 regime, including multiple reviews with opportunities for community boards to delay applications and Council members to veto them entirely, as Streetsblog has documented.

That has led to the bizarre situation of Council members calling applications for sidewalk cafés up for a vote before the entire 51-member lawmaking body, as happened to restaurateurs at Le Dive on the Lower East Side.

Restaurants now hire architects to draw up site plans and land use lawyers just to sift through the morass, and the new obstacles have put al fresco dining out of reach for many cash-strapped establishments, particularly outside of wealthier areas, Moss said.

"Some of the restaurants outside of Manhattan don’t have the money to hire lawyers," he said.

Barone, of DOT, noted that there's no requirement to hire a lawyer or an architect, and that the agency works with each applicant to submit the right paperwork.

The owner of one restaurant in the Bronx where Mayor Adams and Council members ate outside three years ago to celebrate outdoor dining, has decided to forego the program due to the high cost and the many new rules.

"The costs are too high. We pay enough in taxes at is is," said Regina Delfino, owner of Mario's of Arthur Avenue.

Even sidewalk seating was too tricky for the Italian eatery, given that a street tree restricted the space where they could set up to about two tables and chairs, Delfino said.

“The rules and regulations are ridiculous. It wasn’t worth it for it us," she said.

Pedestrian space under threat

There are more than three times as many sidewalk cafés compared to roadway setups, according to DOT, likely due to restaurants not having to set up and dismantle their dining structures each winter, as they now have to do for roadside eateries.

That privileges the car-owning class at the expense of those who don't have an automobile, the majority of New Yorkers, said one pedestrian advocate.

"All the incentives are in the wrong place," said Christine Berthet, co-founder of the pedestrian safety group CHEKPEDS. "We’re saying let’s save car parking but it’s fine to have all the pedestrians conflicting [with outdoor dining] on the sidewalk. There are eight million of us instead of two million of cars owners."

Berthet reviews many applications as the co-chair of Manhattan Community Board 4's Transportation Committee, and she said that sidewalk applications create many more headaches because she wants to ensure they don't clog the path — all while the city's wide roadbeds are right there.

"The roadway applications have been very simple and very easy to approve," the Manhattanite said. "The sidewalk applications are a nightmare because nobody’s measuring the right thing, and because they pay for the full year the operators think that they can enclose the café, which is illegal."