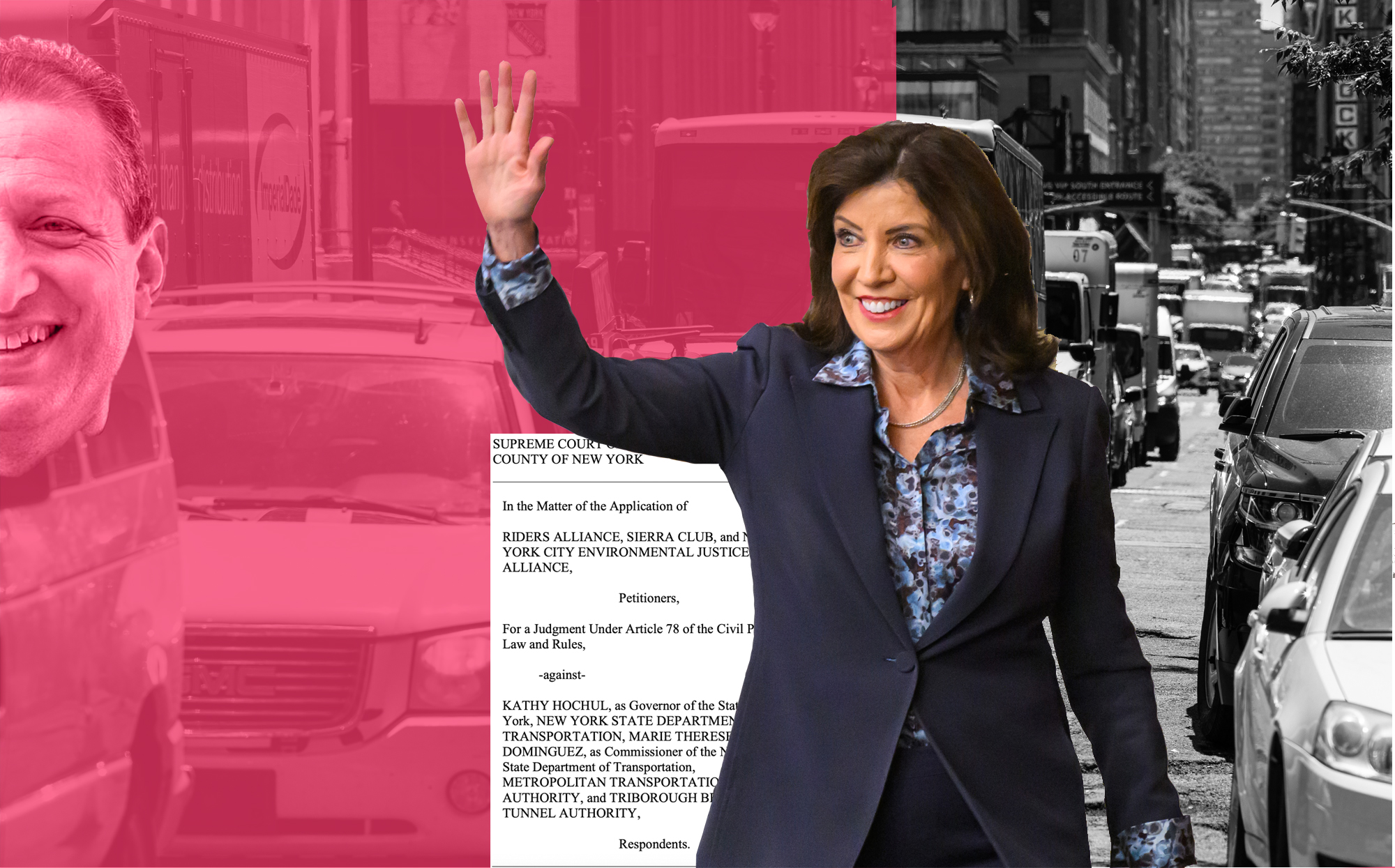

At long last, the threatened lawsuits aiming to reverse Gridlock Gov. Kathy Hochul's congestion pricing pause have been launched. One argues that the pause is illegal because the state must implement congestion pricing; the other says that the governor is violating two of New York's landmark environmental laws.

Will either suit win — or, more important, force Hochul to settle?

Two lawsuits stand before you

On Thursday, congestion pricing advocates and their attorneys gathered outside the David Dinkins Municipal Building to announce they were suing the governor on two fronts.

One group of plaintiffs is suing under Article 78 of New York's civil practice law, a type of lawsuit that allows people to challenge decisions made or actions taken by government officials or agencies. In this instance, the plaintiffs are suing on the grounds Hochul made an "arbitrary and capricious" decision when she ordered the congestion pricing pause, and that telling state Department of Transportation Commissioner Marie Therese Dominguez to not sign a federal document allowing congestion pricing to begin violates the law because Dominguez doesn't have a choice when it comes to signing the document.

The crux of the suit is simple: because the law establishing congestion pricing, known as the Traffic Mobility Act, demands that the MTA "shall ... plan, design, install, construct, and maintain a central business district toll collection system," Governor Hochul doesn't have the authority to pause it. According to one of the lawyers arguing the case, the issue at hand isn't just congestion pricing, it's about whether or not we live in a society governed by laws.

"This is a case about democracy," said plaintiff's attorney Andy Celli. "It's a case that asks the question whether an executive official is allowed to defy the law, to ignore the will of the legislature, to upend a decades-long process of policymaking simply because at the last minute she changed her mind. The obvious answer to this question is no."

Another group of plaintiffs says that Hochul's pause violates two recently passed state environmental laws. The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which mandates the state reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030 and by 80 percent by 2050. The other is the so-called "Green Amendment," an amendment to the state constitution guaranteeing New Yorkers "a right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment" that was passed by a ballot referendum in 2021.

Clearly, the attorneys argue, Hochul's decision to cancel congestion pricing violates New Yorkers' right to clean air and a healthful environment, since it upends a plan to lower emissions and reduce vehicle miles traveled. And because the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act resulted in a plan in which the state recognized the need to greatly reduce VMTs statewide to hit the climate goals, attorneys argued that Hochul is kneecapping that law by refusing to implement congestion pricing.

"[The CLCPA] means that every official in state government from the governor on down needs to take account of whether their actions help get us towards our goal of reducing emissions, or take us further from it," said Dror Ladin, a plaintiff's attorney with the environmental justice organization Earthjustice. "There's no question what the governor has just done is absolutely at odds with the requirements of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act."

Will this work?

Both cases have a tough road ahead.

In the Article 78 lawsuit, outside legal experts note that the field is tilted towards the government because judges are not leaping out of their robes to force elected officials to take one action or another. Readers of Streetsblog are no doubt familiar with a bevy of tossed-out Article 78 lawsuits attempting to stop the city Department of Transportation from putting in busways and bike lanes.

"Courts are going to be very deferential to the government's decision making," said Michael Pollack, a law professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. "The 'arbitrary and capricious' standard is a very low bar for the government to meet; it's essentially [does the government have] some plausible, not arbitrary reason. They don't need to prove scientifically that there's this causal connection between car usage or car deterrence and the rebound of the central business district. They can sort of gesture toward that and say, it was not arbitrary for us to think that there would be this connection."

But Hochul will still need to answer the charge that her decision to use the state DOT to block congestion pricing wasn't driven by an arbitrary and capricious decision making process. And in that sense, Pollack said that the governor's lack of a credible explanation for the pause could hurt her in court.

"One of the reasons why a lawsuit is a challenge, but also a reason why the governmental actions here are themselves vulnerable to the lawsuit, is that it's so murky what the relevant actors have actually done here," he said.

Hochul hasn't provided any studies showing that implementing congestion pricing would, for instance, hurt Midtown's Covid recovery or that stopping the toll would protect New Yorkers from higher costs. She also hasn't explained how long the purported "pause" is supposed to last or what conditions would end it. The yawning gap between what she's said publicly and how a state agency is supposed back up its decision-making processes leaves plenty of room for a legal wedge.

"That sort of oddity makes it sort of like trying to nail Jell-o to the wall," said Pollack. "It's hard to tell what exactly you're litigating against, while, at the same time, it's quite likely that whatever has happened here is not consistent with the congestion pricing statute, or with the administrative procedures that are typically followed. It's odd, and it's certainly not how government agencies are supposed to make decisions. ... This is no way to run a railroad."

Another prong of the suit argues state DOT Commissioner Dominguez doesn't have the discretion to not sign the federal government's Value Pricing Pilot Program agreement that formally implements congestion pricing. That signing, Celli and co-counsel Richard Emery argue, is a ministerial decision — aka one that's mandated by law — because the Traffic Mobility Act states that the MTA "shall" start a congestion pricing program.

If a judge agrees, Pollack said, said judge could order Dominguez to sign the VPPP agreement.

The other lawsuit is a much more wide open field of law. Both the CLCPA and the Green Amendment are untested in terms of existing case law, with the CLCPA in particular having a light legal footprint so far. The law's main enforcement mechanism to ensure the state stays on its emissions target is lawsuits brought by any party that claims to be harmed by the state missing said emissions targets.

As for the Green Amendment, in 2023 a judge threw out one of the first lawsuits brought under the amendment, which was filed by Lower Manhattan residents attempting to stop a developer from building several towers near the Manhattan Bridge.

Outside experts also say that the laws themselves don't necessarily point to "implement congestion pricing" as something New York State has to do.

"In general, the Green Amendment is a really hard thing to enforce because it doesn't contain any clearly defined standard for what constitutes a sufficiently clean environment," said Professor Roderick Hills Jr., who teaches Constitutional law at New York University.

"The [CLCPA] is a little more specific. But it's kind of tricky, too because ... it defines goals but it doesn't say, and therefore you must do X, Y, or Z. If you think of the CLCPA as a substantive rule that says you've got to follow its scoping plan, well that plan doesn't say you have to have congestion pricing. It just says to do what's necessary to minimize VMT impacts. So you can see why if you treat this as a substantive set of requirements, it's a little bit daunting for a Supreme Court justice to decide congestion pricing is the thing that the law requires," he said.

That doesn't mean the suit bringing those arguments is cooked though.

Under the CLCPA, a state official has to make the case that an environmental decision either fits into the state's larger emission reduction goals, or the official has to give a detailed justification for taking an action that cuts against those goals. So far, Commissioner Dominguez has done neither of those things. If the silence is a tacit endorsement of Hochul's flailing justifications for trying to avoid implementing congestion pricing, or Dominguez herself fails to explain in a substantive way why she won't sign off on congestion pricing, the plaintiffs could prevail though.

"If Dominguez says nothing substantial, if she's as flippant as Hochul was, and gives no reasons, that might be irritating enough to a responsible judge that they will say you actually have no authority to withhold your signature under Article 78. There's an interaction between these two arguments. Article 78 says, look, this is not your responsibility, you have no role to play here. Will a judge buy that as an abstract matter? Maybe, maybe not. But if the person who's playing a role, then basically gives a third finger to the entire 2019 environmental law a judge is much more likely to say, you really have no role to play here," said Hills.

In that sense, Hills said, the suits play off each other, with the Article 78 suit acting as a pure legal argument and the suits over the environmental laws laying out an emotional hook to allow a judge to grasp how ill-considered the governor's decision making has been in the context of the state's stated climate goals.

"The way a lawsuit works is that there's music and then there's lyrics. The lyrics are the technical legal theory. But if you don't have a good tune, often it's hard to get the judge to sing along, so the music is the emotion behind the lawsuit. Why is it legally relevant Governor Hochul is acting as an unprincipled, political, opportunist? There's no law against being a political opportunist, if there were the state government would shut down. But if you combine that emotion that this is pure political opportunism without any principle to it with a legal theory, which supplies the lyrics, the two together make it much more likely that a judge will feel confident in ruling against the governor," he said.

In addition, the lack of case law also means that attorneys for Earthjustice see an opportunity to determine what both laws mean in practice.

"There is some lower court decision-making on the CLCPA, but there's not a ton of it. There are a few lawsuits percolating and this could be one of them that establishes its contours and how much it protects us," said Ladin. "This is a good case that really sets up what does this constitutional right protect? And if it doesn't protect this, it's hard to know exactly what it would protect."

As for the defendant in the suit, Gov. Hochul, of course, also thinks she has a good chance of winning in court, issuing a baffling statement lumping in the lawsuits trying to stop congestion pricing with the suits trying to ensure the program starts.

"Get in line," said Hochul spokesperson Maggie Halley about the latest suits. "There are now 11 separate congestion pricing lawsuits filed by groups trying to weaponize the judicial system to score political points, but Gov. Hochul remains focused on what matters: funding transit, reducing congestion, and protecting working New Yorkers."

Left unsaid in Hochul's statement was that New York State is defending itself in the nine other lawsuits that seek to stop congestion pricing. Also left unsaid — still — is Hochul's plan to fill the $15-billion hole she blew in the MTA capital plan or how she will reduce congestion.

Hochul's legislative partners appear to be losing patience with the gridlock governor. State Sen. Jeremy Cooney, the new Transportation Committee chairman, recently published an op-ed criticizing the congestion pricing pause for its potential to cost upstate New York 100,000 jobs in lost MTA contracts.

"The time for debating the merits of congestion pricing has passed, what is most important is keeping our promise to the passengers and workers impacted across the state," Cooney wrote in his op-ed, before challenging the governor to solve the mess in 100 days.