Long Island City should become the first city neighborhood with a fully connected network of protected bike lanes, a Queens politician said on Wednesday, as he called on his car-loving constituents to give up some of their precious parking and, perhaps more important, their notions of how the streets should be used.

Queens Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer joined about a dozen bike advocates on Wednesday morning to demand the city create the first-of-its-kind network of protected bike lanes in Long Island City — where a driver struck and killed 53-year-old Robert Spencer as he was cycling along Borden Avenue. Since January, there have been a total of 597 injury-causing crashes in Western Queens alone, including the crash that killed Spencer and another that killed an 88-year-old man in Astoria.

In March, Spencer became the sixth person killed on Mayor de Blasio’s streets. It’s now barely August, and that number shot up to 18 — it cannot become 19, said Van Bramer, standing on a pedestrian plaza on the Queens side of the Pulaksi Bridge.

“Eighteen cyclists have been killed already this year — not inconvenienced, not delayed, they are dead," he said. "We know what saves people's lives. We just have to do it and we have to do it before more people are killed under the wheels of trucks and cars."

Our proposal for a protected bike lane network in LIC comes in the wake of Monday's news that an 18th cyclist was killed in NYC this year. One of those 18 was LIC resident Robert Spencer, who was killed riding his bike on Borden Ave.

— Jimmy Van Bramer (@JimmyVanBramer) July 31, 2019

Not one more! @TransAlt @bikenewyork pic.twitter.com/xNySJuigL6

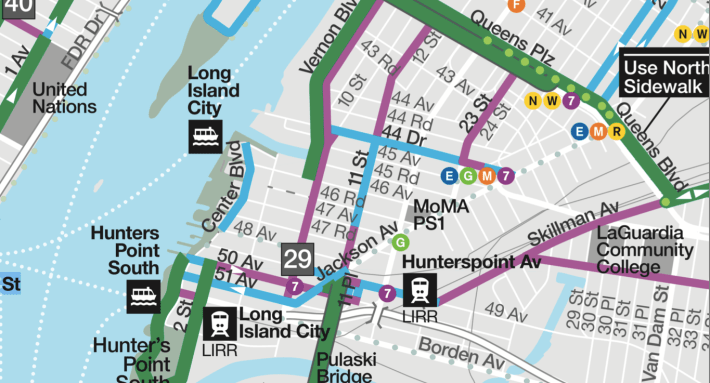

The Queens pol wants protected bike lanes to cover the entirety of the neighborhood, including on popular routes like the full length of Jackson Avenue, Vernon Boulevard, Center Boulevard, Skillman Avenue west of Queens Boulevard, and 48th Avenue, according to the map he proposed along with the advocacy groups Transportation Alternatives and Bike New York. The network would link to existing greenways and local cultural institutions, and would be a closed circuit, meaning riders would always be just a few blocks from another protected bike lane.

Long Island City is home to both a high number of cyclists and unfortunately a high number of crashes — its wide streets lack any real protection to separate cars and trucks from bikers — and the neighborhood is past due for improved bike infrastructure so Queens cyclists can commute safely across the East River, said Transportation Alternative's Queens Juan Restrepo.

“Some of the highest bike density is here in Long Island City — since the Greenway, there hasn’t been serious innovation to get people safely to Manhattan and back to Queens."

Other communities could and should look to Long Island City as an example of what could be done to protect bikers on the road, said Restrepo.

"We want Long Island City to be the first bike neighborhood," he said.

On July 25, the mayor unveiled his Green Wave plan to finally stop the bloodshed on city streets — it calls for building out 30 miles of protected bike lanes across the five boroughs each year, a large portion of which would be built out in 10 communities identified as Bike Priority Districts. Long Island City is slated to get some protected bike lanes as part of the plan, but it is not one of the priority districts. And the de Blasio plan does not call for the kind of network Van Bramer envisions.

Van Bramer, who is running for Queens Borough President and who recently denounced the Queens community board member who said pedestrians “deserve to get run over,” unveiled his demands for a full Long Island City protected bike network on the same day a State Supreme Court Justice denied an effort by wealthy Upper West Side condo owners to halt a life-saving protected bike lane on Central Park West.

It’s a battle safe-street advocates have unnecessarily had to fight before — a decade ago, some wealthy Brooklynites sued to stop the city from building the now-popular and life-saving Prospect Park West bike lane. Their suit was ultimately dismissed.

“We saw an almost carbon copy lawsuit against the Prospect Park West bike lane in 2010. The bike lane went in, it’s been a fantastic community facility for years now and the lawsuit was abandoned. There was no merit to it," said Bike New York's Jon Orcutt.

Van Bramer is ready to fight anyone else who is willing to risk people's lives.

“Anything that delays life-saving measures is reckless and dangerous, we got to push forward and push through against any inevitable delay tactics," he said. "People have died on these streets in Long Island City, what more do we need to convince ourselves that we need a connected protected bike lane network? How many more people need to die before we all agree that we have to do this?”

Van Bramer is a recent and passionate convert to the glory of protected bike lanes. The Queens lawmaker has championed road safety in the past, but got into a huge political fight with some of his car-loving constituents over a pair of now-popular bike lanes through Sunnyside. After cyclist Gelacio Reyes died on 43rd Avenue in 2017, Van Bramer called for a protected bike lane on the dangerous roadway — only to back away from the proposal when the city designed paired protected lanes on 43rd Avenue and neighboring Skillman Avenue. He hid for months, but eventually supported the city plan — and admitted that he regretted his ambivalence.

Since then, Van Bramer has been a very aggressive supporter of street safety issues and a regular attendee at the all-too-often vigils.

A spokesman for the Department of Transportation said it shares Van Bramer's vision for a protected bike network in Long Island City and will work with the community to implement one.

"We are in fact looking at a number of the corridors mentioned in today’s press conference, and next year we are planning to do more work with Western Queens communities focused on protected bike lanes," said the spokesman.