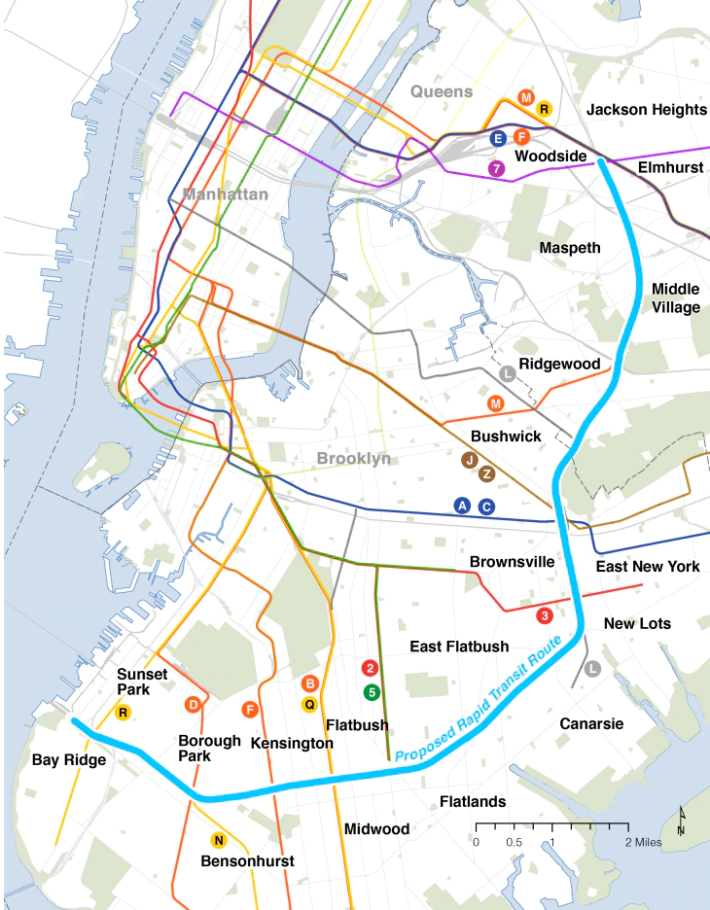

The road ahead is hardly certain for the proposed $5.5-billion “Interborough Express,” or IBX, light rail line, but Gov. Hochul and the MTA are off to a strong start thanks to their decision last year to run the line under All Faiths Cemetery — which opens up the possibility for fast, more effective service.

Hochul and the MTA last Friday unveiled vastly improved speed and ridership estimates for the line, in large part thanks to the inclusion of a tunnel under All Faiths Cemetery. The IBX will now run 32 minutes end-to-end from Sunset Park to Jackson Heights instead of 42, with 160,000 daily passengers instead of 121,000.

These changes position the IBX as something more than the light rail line officials have advertised, and that’s on purpose. In May, MTA officials at an IBX open house in Jackson Heights described the project to me as “high capacity light metro” — a subtle but consequential shift from “light rail.”

“The key thing with the light metro is that it’s gonna be high speed and it’s gonna have a lot of capacity,” IBX Project Executive Charles Gans told me.

Light metro vs. light rail

MTA officials calling the IBX “a light metro project" rather than simply “light rail" represents a significant semantic shift.

While light rail is a broad category in American transit, it often entails smaller vehicles designed to travel at deliberately lower speeds due to on-street segments or at-grade crossings.

Initial IBX project renderings pointed in this direction, with images of smaller vehicles akin to those seen in Europe and some North American cities shown alongside L trains at Wilson Avenue and freight trains in Jackson Heights. (The proposed route also included an extended on-street segment so the MTA could avoid digging under All Saints Cemetery.)

Light metro, also known as medium-capacity rail, is a step above light rail — a middle ground between street-level trams and full size subway networks.

Like subways, light metro systems usually run separated from other traffic. This allows for faster trains from the start that don’t have to incorporate road and traffic-friendly design features. That in turn helps avoid potential operational pitfalls like those that befell the light rail trains in Ottawa, Canada, where trains designed for on-street use had to be modified beyond their limits to act more like subway trains to the point of breaking.

While light metro trains are still smaller than, say, New York City subway trains, they make up for this by running at incredibly high frequencies thanks to automated operation, helped in many systems by platform-screen doors in stations that make incidents on station tracks extremely rare. The exact details of the IBX are yet to be determined, but officials’ updated speed and ridership estimates underscore the MTA’s honing in on the light metro model. It also fits with the authority’s intent to expand the number of suppliers for the project.

“One of the things we like about it is there are more manufactures that make those types of cars. That has us—we won’t be getting in the way of subway or railroad procurements,” MTA Construction and Development official Sean Fitzpatrick said at the May open house.

In keeping with that goal, and to show some of the best practices the MTA can copy, it is worth looking at a few light metro systems the MTA can use as examples. While the concept may be new to New York (sort of — we’ll come back to that), many cities across the US and world have built light metros in recent decades.

There’s much inspiration to draw from:

Montreal's REM

Launched in 2023, Montreal’s REM is an automated light metro network and one of the highest profile rail projects to open in North America in recent years. Gans told me REM “often comes up in conversations about the IBX."

It's easy to see why: Like the IBX, most of the REM network reuses abandoned or underused rail alignments in the greater Montreal area. This includes, among others, the Deux-Montagnes commuter rail line, large parts of which were elevated to allow frequent rapid transit service, and the century-old Mont Royal tunnel, which was refurbished to support rapid transit service and new stations connecting the REM with the existing subway.

The automated system is capable of running trains as frequently as two-and-a-half minutes apart during busier periods. The sheer intensity of service means Montreal officials expect the system to carry 190,000 riders a day when fully operational.

It is as good a network to start with as any, and it is encouraging the MTA is talking about it, at least internally.

London’s Docklands Light Railway

Conceived as a low-cost way to get rapid transit to London’s Docklands area, the DLR has become a second subway system for London. It carried 405,000 passengers daily on weekdays pre-pandemic through a sprawling network in East London made up mostly of reused railways, with a few newer extensions as well.

Like the REM, the DLR’s advanced signaling allows an extremely high number of trains to run at any one time. This is made more impressive by the DLR’s complex spaghetti bowl of six routes operating frequent, intersecting services.

The DLR has achieved this despite being in a near-constant state of flux: Initially expected to serve only small-scale development, the DLR has added more and more riders, spurred on by the development of large office complexes like Canary Wharf. This expansion required modifications to stations over time to support more passengers, as well as the gradual lengthening of trains. Additional help came with other rail expansions to alleviate crowding.

This has all helped create a system that, despite being a light metro, rivals many other larger rail systems in service and ridership intensity. It is an excellent model for the MTA to follow, not just for the IBX as planned now but for any potential expansion — perhaps to Staten Island, LaGuardia Airport or the Bronx.

Vancouver’s Skytrain

No discussion of light metro is complete without the system that helped publicize it.

First opened in 1986 as a showpiece of a transportation-themed world expo, the Skytrain has grown to become a key part of Vancouver’s transit network. Like the above systems, many prominent parts of the network run on old tracks, notably the tunnel used by Expo Line trains in downtown Vancouver and several interurban rights-of-way.

The system has expanded almost continuously since opening, and briefly became the largest automated rail network in the world in 2016 before systems in Asia and the Middle East surpassed it. Several extensions are in planning or construction.

Of particular note, however, is the way successive regional governments have made development around Skytrain stations a priority. Intensive transit-oriented development around stations is commonplace, with suburbs like Burnaby and Surrey seeing transformational growth around stations to the point of skylines developing. The population growth of Vancouver over the past few decades, in fact, can be partially attributed to the amount of housing Skytrain extensions have been able to generate through modified zoning.

IBX advocates tout the line as a way to build new homes in areas relatively close to Manhattan and other job centers. Like the Skytrain, the amount of development the IBX will generate will be transformational. The more thought and planning that can go into integrating this development with the area, the better.

Our own JFK AirTrain

Speaking of airports, it would be remiss to not mention the one modern light metro system New York already has: the JFK Airport Airtrain.

The JFK Airtrain is a system born out of compromise. Initially planned to go all the way to Manhattan, as built the service operates as a short people mover connecting JFK Airport to LIRR and subway at Jamaica and Howard Beach. It’s the only fully automated rail network in New York state, besting the L train’s full signal automation by six years, and is the only network to have platform screen doors installed at every station and platform, making it one of the safest rail systems here by default.

Like the other systems mentioned, a certain amount of future-proofing is built in, with trains as long as four cars able to run extremely close together thanks to automated signals.

Unfortunately, the system often never comes close to meeting this capacity, with pitifully long off-peak frequencies and shorter trains than it is built to handle.

Nonetheless, the AirTrain is the most technologically advanced transit line in the New York region, by far. It is on par with systems already mentioned above and, in the case of the DLR and Skytrain, arguably a tad better with its use of platform-screen doors. It’s also the only fully-automated transit system in the city — proof that driverless transit can happen in New York City even with our powerful labor unions.

More than anything, the AirTrain shows an effective, automated metro can work in New York — including on the IBX if the MTA has the courage.