Would New Yorkers rather promenade or meander?

This is the question facing the city's Department of Transportation, which will spend $89 million to revamp Paseo Park and fully build out the 1.3 mile-long 34th Avenue open street in Jackson Heights that became a pandemic-era model for reclaiming space for pedestrians, cyclists, and children.

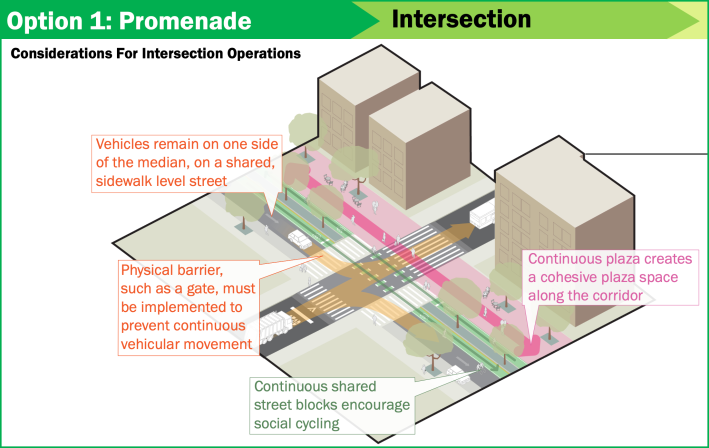

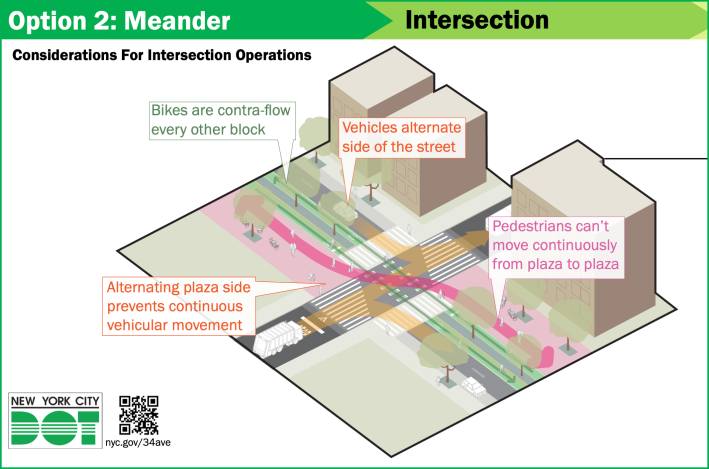

After months of gathering local feedback, the DOT narrowed its redesign plans into two options [PDF]: Option 1 offers a straight "promenade" design that divides pedestrian plazas and "shared traffic" lanes into parallel corridors, whereas Option 2 offers a zig-zagging "meander" design that switches the pedestrian plazas and the shared traffic lanes at every intersection.

Shared traffic lanes permit drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians to use them simultaneously, albeit with barricades to inhibit drivers so they feel like guests, as opposed to what they are on every other street: tyrants to whom everyone else must cower.

So what's what?

Compare the following isometric illustrations created by the DOT for transforming what it once called its "gold standard open street" into a true linear park. First, "Promenade" (Option 1):

And here's "Meander" (Option 2):

The most noticeable difference between the two options is how each manages drivers and maximizes open space on the roadway.

Option 1 would employ a "physical barrier, such as a gate" to prevent automobiles from plowing straight through intersections. That means that a driver would need to exit his or her vehicle, open the gate, return to the vehicle, drive past the gate, exit the vehicle again, close the gate, and then return once more to the vehicle.

By contrast, Option 2 would alternate the shared traffic lane and the pedestrian plaza for each block to accomplish the same goal, using the pedestrian plaza as a de facto barrier.

The DOT deployed some of these features, including contraflow bike paths and alternating traffic lanes, in its transformative redesign of 31st Avenue in Astoria. But the implementation of a permanent "physical barrier" or "gate," which can be found in some older city parks, would be a novel approach for an open street. Every other comparable open street, such as Berry Street in Williamsburg, has employed flimsy steel barricades that can be moved aside or simply driven over by a determined motorist.

The two options have similarities: Both move the park’s existing curbside bike lanes into the very center, hugging the grassy median. Neither option attempts to inhibit the movement of cyclists.

More radically, both options would remove all elevation changes, so the median, the bike lanes, the pedestrian plazas, the sidewalks, and the shared traffic lanes will sit on the same plane. Hence, the "park" part of Paseo Park.

Neither option is entirely fleshed out. Certain details, such as precise traffic diversion patterns and two "atypical block designs" on the park’s western half, have not yet been finalized. But both options would create — or preserve — large pedestrian plazas that are entirely devoid of cars, mopeds, and bicycles at all times. The DOT says its design process will continue for several more years, through at least 2028.

It isn’t clear which option will prevail — or whether the DOT will go back to the drawing board. Two major stakeholders, the 34th Avenue Open Streets Coalition and the Alliance for Paseo Park, differ on the best choice.

Jim Burke, the co-founder of the Coalition, which runs daily programming in the park, told Streetsblog that his group preferred Option 2 (the "Meander") because it "preserves the real beauty of what we have now, whereas the Promenade option might degrade the experience of walking and biking." He added: "'Meander' is [the status quo] on steroids. That means more plazas and car-free areas — that’s what we really love about it. We currently have plazas on seven blocks. The 'Meander' would give us many more."

But Luz Maria Mercado, the board chair of the Alliance, which formed to advocate for a long-term vision of the park, said her non-profit wasn’t satisfied with either option because neither properly addresses the presence of moped users.

"We appreciate DOT’s recent outreach, but the current proposals still fall short of delivering the end-to-end, pedestrian-first experience our community deserves," Mercado said. "To truly deter dangerous mopeds from cutting through Paseo Park, our community roadmap calls for a dedicated micro-mobility lane on a nearby corridor such as Northern Boulevard."

What will happen? DOT is still collecting feedback at this link through Nov. 30. A preliminary design will be unveiled next year, which will kick off another round of outreach and design tweaks. There is no date set for construction to begin beyond the word "future" on the DOT schematics.

For more details, click here.