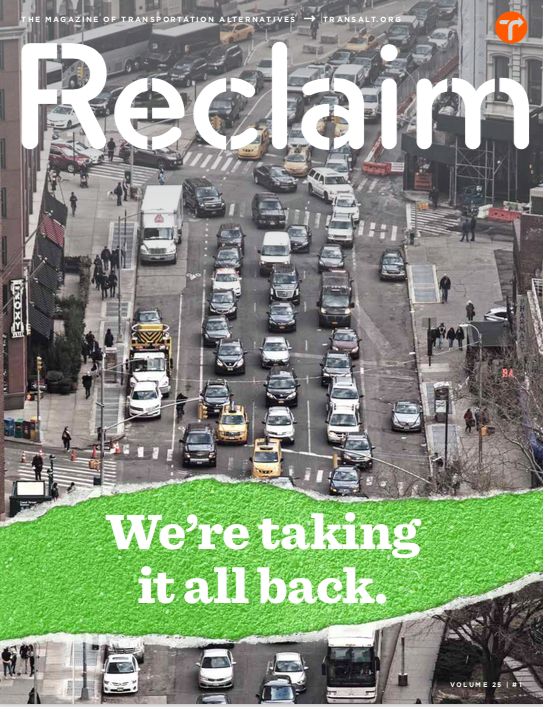

This is a sneak-peak at the new issue of Reclaim, the in-house magazine of Transportation Alternatives. All TransAlt member get a free subscription to Reclaim magazine — join at transalt.org/membership.

In October 2017, Mayor Bill de Blasio stood behind a podium on the Upper West Side to announce an immediate crackdown on the use of electric bicycles, also known as e-bikes. When asked later to quantify the safety issue, he could not. It is about complaints, he admitted; no one has ever been killed by an e-bike in New York City.

While New Yorkers of all stripes had been using electric bikes to traverse the city for years, Mayor de Blasio was clear about which ones he would be targeting — “the kind of bikes that the delivery folks use.” The crackdown was swift and devastating. Despite claims that summonsing would target business owners, delivery workers received more than 87 percent of the summonses. Police also confiscated the means of workers’ labor, seizing at least 1,000 e-bikes last year — including nearly 250 in one day — and leaving workers without a way to do their jobs. One delivery worker, Xiaodeng Chen, told the Village Voice that he nets $80 to $100 per ten-hour shift. If his e-bike was seized, it would remain under police lockdown until he paid $500 to $1,000 in summonses — impossible, unfair math. Research by Dr. Do Lee of the Biking Public Project in 2017 found that Spanish- and Chinese-speaking delivery workers earned on average almost $5 an hour less than English-speaking delivery workers, and faced a greater burden in the crackdown, with Chinese-speaking and Spanish-speaking workers paying an average of $420 and $190 more in fines and fees, respectively, than their English-speaking counterparts.

A little over a year after Mayor de Blasio’s press conference, Citi Bike announced plans to roll out 4,000 shared electric bikes, with city authorization (though the bikes have been grounded temporarily in a repair crisis). A TransAlt activist named Brian Howald found himself riding one of those electric Citi Bikes past a temporary digital billboard owned by the city. “E-Bikes are illegal,” it flashed. Howald snapped a photo and posted the incongruity on Twitter.

It’s a tale of two e-bikes, for sure. And it’s about to get a lot more complicated. Thanks to a pile of start-up cash, a struggling transit system, and some major advances in battery technology, the e-bike market is ripe for a huge expansion in New York — along with the scooters, e-scooters, and dockless bike share systems that make up the exploding “micromobility” industry.

Micromobility is a Silicon Valley term for tiny vehicles used for urban transportation. It loosely includes anything that eschews gasoline and transports one or two people — electric and people-powered bicycles, skateboards, scooters, even small electric cars. Your Schwinn certainly counts, but the term — and the massive startup industry behind it — is really about shared public transportation. The industry’s biggest bet is electric: bikes and scooters that run on battery and zip between 10 and 30 mph. More than $5.7 billion has been invested in micromobility startups in the past few years.

These tiny vehicles could bring a sea change to New York City’s streets, resetting the dominant paradigm of “cars first” and multiplying the ranks of people like you — New Yorkers fired up to demand more space for biking and walking.

New York City has vast potential as a proving ground for micromobility. It’s flat, not very big, and currently crowded with trips made unnecessarily by car — like taxi rides, the majority of which are shorter than a scooter-friendly three miles. Right now there are multiple bills in the City Council that would clarify and open up the legal status of electric scooters and bicycles, and the Department of Transportation is currently considering how and when to let e-scooter share start-ups in New York’s front door. Even the Gray Lady is in, recently endorsing e-bikes and e-scooters on the New York Times editorial pages.

“There always will be New Yorkers who complain about cyclists — and, perhaps soon, scooters — blaming them for ills both real and imagined. But bikes and similar vehicles take up far less public space and are much more environmentally sustainable than cars,” the editorial board wrote. “If the city is serious about wanting safe, reliable ways for people in all areas of New York to get around, the path ahead is clear.”

And if you read past the headlines, there’s a deeper story here, one that goes all the way back to Robert Moses. “The scooters are forcing conversations about who is entitled to use sidewalks, streets, and curbs, and who should pay for their upkeep,” environment reporter Umair Irfan wrote for Vox last year. “They’re also exposing transit deserts, showing who is and isn’t adequately served by the status quo, and even by newer options like bike share. That people have taken so readily to scooters shows just how much latent demand there is for a quick and cheap way to get around cities.”

In low-income communities and communities of color, historic neglect and disinvestment in transportation infrastructure have created disproportionately dangerous streetscapes with little access to public transportation options. And thanks to the highway-enamored transportation policies of the 1950s and 60s, the vast majority of the space between New York City buildings is dedicated to free parking and driving — even though only a minority of New Yorkers drive to work, most of whom are well-off. Since Moses became chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority in 1934, car drivers have killed more than 49,000 people on city streets. New York is long overdue to confront and address this destructive legacy. Micromobility could be part of the solution.

With all this in mind, Transportation Alternatives researchers have spent months in the weeds of the data, and we are ready to unveil our allegiances: rev up the e-scooters and count us in. We are ready for the micromobility revolution. It may be a messy few years of acclimation, but the proliferation of tiny vehicles could turn the gridlocked, car-centric, and deeply unfair city built by Robert Moses into a thriving, accessible, and much safer metropolis.

To achieve Transportation Alternatives’ mission to reclaim New York City’s streets from the automobile, we need to break the mentality that cars are good and necessary for the city — a mindset that dominates even among car-free New Yorkers. Breaking New York’s car culture will require giving New Yorkers immediate, viable, and accessible transportation options. Micromobility is price-diverse, city-scalable, and, with its penchant for slow-going motors, manageable for an aging city population. One study found that 34 percent of scooter riders in Portland, Oregon, would have taken a car if a scooter had been unavailable. That’s the kind of impact that could drive our mission toward completion.

This endorsement, of course, in no way gives e-bikes and e-scooters a pass. TransAlt expects micromobility companies to come to New York with solutions for New York City problems, not just profit margins, in mind — and if these start-ups fail to serve all New Yorkers, we will hold them to account.

Access to transportation is one of the single most important factors in upward mobility from poverty, and micromobility companies can help by preparing to launch in low-income, transit-starved communities from day one. That means more than dumping e-scooters in East New York before a press conference and never bringing them back. Shared electric vehicles should be accessible to all New Yorkers, with discounted usage rates for NYCHA residents and SNAP recipients, cash-only sign-up options for the unbanked at local stores, and the ability to use NYCLink stations to locate and access them if you don’t have a smartphone.

Beyond equity, space is an issue we need to be ready for. Embracing micromobility must include taking space from cars. Bike lanes should be widened to accommodate passing at a diversity of electric and non-electric speeds, and every intersection in the city should receive daylighting (the removal of the parking spaces closest to the intersection). This will create drop-zones for shared micromobility vehicles that are safely away from the sidewalk, and will dramatically improve drivers’ visibility of people walking and riding — especially those who use wheelchairs.

The city should also avoid capping the number of tiny vehicles permitted in the city. While concerns about safety and space sharing are real, caps on micromobility roll-outs could prevent “safety in numbers” protections and put riders in danger. “Strong empirical evidence suggests that the best thing we can do to ensure the safety of scooter riders is to increase their number,” mobility researcher Peter Jacobson wrote in the latest issue of TransAlt’s Vision Zero Cities Journal. “As tiny vehicles become more common, motorists will increasingly be on the lookout for them. More rapid motorist perception will translate into fewer collisions. Not only that, but as the number of urban scooters increases, collisions will likely become less severe.”

As for enforcement, the wrongheaded e-bike crackdown initiated by Mayor de Blasio must end, and the city should help delivery workers convert their Class 3 throttle e-bikes to legal slower e-bikes. The NYPD should recommit to Vision Zero policing based on danger, not complaints. As for the rules, shared electric vehicles should be given the same rights and responsibilities as bicyclists: allowed in bike lanes, prohibited on sidewalks, required to yield to people walking, and with cars and trucks required to yield to them. It’s also time to expand automated enforcement, with new camera technology that can keep bike lanes and intersections clear of cars.

It won’t take long for people on tiny vehicles to become just like people on bikes — with a street-level perspective on the danger and unfairness of the current share of our streets, and readiness to fight for change. Micromobility is the route to a broader, more powerful movement for more and wider bike lanes and new transportation alternatives. Starting this spring, and growing at a rapid clip in the coming years, expect conflicts in the bike lane between a new mix of scooters, e-scooters, bikes, and e-bikes — and take it as an opportunity for new conversations about how New York’s streets are shared. Reclaim readers know cars are the problem, but most New Yorkers are so inured to 80 percent of their public space being given over to automobiles that they don’t even see the vast potential of a parking space. Micromobility, even if it means a crowded bike lane, has the potential to become the dominant mode share. Get ready for some hard conversations in the bike lane and on the sidewalk about why we should stop fighting for scraps of the road. It’s time to reclaim the streets.

For further reading on this topic, check out Micromobili-What? and Who’s in Charge Here?