This article was originally published in the Vision Zero Cities Journal, as part of Transportation Alternatives’ 2025 Vision Zero Cities conference, which will take place Oct. 28-30 in New York City.

Two years after the Second Avenue Subway made headlines as the most-expensive mile of subway ever built, costing $2.5 billion per mile, Istanbul was named by the International Public Transport Association as the global leader in heavy rail construction.

At the time, the city had 13 projects under construction, totaling 135 miles, at an average cost of just $224 million per mile (adjusted for purchasing power parity and inflation). The Transit Costs Project, a global comparative study of urban rail construction costs, found that U.S. projects are often five to ten times more expensive than those in countries like Italy, Sweden, and Türkiye due to factors such as station design, lack of standardization, inefficient management of labor, procurement practices, and soft costs. In particular, American cities could learn from Istanbul, one of the project's case studies that illustrates how a city effectively addressed similar challenges to expand its subway network efficiently and affordably, despite deep political divisions and ongoing economic turmoil. Building urban rail fast and cheaply allows more miles of subway to be built, improving transit access, expanding opportunity, reducing car use, easing congestion, lowering pollution, supporting healthier communities, and advancing a more sustainable future aligned with Vision Zero goals adopted by over 60 U.S. communities.

Over the past three decades, Istanbul has expanded its subway network by more than 200 miles, with an additional 50 miles of lines under construction as of June 2025. During those years, Türkiye went through multiple political and financial crises, and tensions between the ruling and opposition parties often spilled into the city’s politics and jeopardized transit funding.

Adding to these challenges are Istanbul’s complex physical conditions: most construction sites are near the water or below the water table, the city lies in an active earthquake zone, and its rich archaeological heritage and aging building stock further complicate underground work. And yet, the public agencies in collaboration with private industry have consistently delivered new lines, at an average cost of $236 million per mile — 72 percent below the American average — with 80 percent of the lines in tunnels and projects winning international design awards.

The Transit Costs Project identified multiple cost-saving practices in Istanbul that mirror lessons from cities like Milan and Stockholm. These insights — including streamlined processes, a flexible collaboration between city agencies and the private sector, the accumulation of expertise over decades, and investment in technology and innovation — can inform better practices in cities in the U.S. and around the world.

Between 1950 and 1990, Türkiye’s population nearly tripled, with urbanization increasing from 25 percent to over 56 percent. In response, the country implemented a series of reforms that harnessed urban growth to drive economic development. A new metropolitan municipality regime centralized planning and infrastructure authority in cities, while legalizing informal land rights spurred private investment in housing. Expansion of the housing stock was further supported by mortgage-based financing, and public-private partnerships were introduced to help fund essential municipal services like water and sanitation. These policies attracted significant domestic and foreign investment, fueling a construction boom in the early 2000s. Along with housing, many megaprojects were realized through public-private partnerships financed by both local and international loans, backed by state guarantees.

Istanbul’s first metro project on the city’s Asian side, the 13.5-mile M4 line, faced significant early challenges due to limited institutional capacity, poor preliminary planning, and shifting project scopes. Initially proposed as an at-grade light rail line, the project underwent multiple redesigns, including a conversion to fully underground heavy rail. These changes led to major cost overruns and delays and highlighted the importance of robust pre-construction design and the need for clear oversight structures.

A key factor that helped rescue the troubled M4 project was the flexibility shown by both the agency and the contractors, but ultimately, the creation of the Projects Directorate under the Rail Systems Department of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality in 2014 marked the most significant advancement in efficiently managing subsequent rail projects. The Directorate centralized planning capacity and began requiring 60 percent design documentation before tenders, while remaining open to revisions proposed by the contractor’s design team during implementation. This shift helped the municipality streamline the procurement and project management processes and improved costs and delivery outcomes. The Rail Systems Department’s modest in-house capacity has not hampered its work, thanks to improved efficiency in managing consultants and contractors, as well as a competitive market with an abundance of firms.

The agency’s flexibility continues to pay off. During the M7 metro line’s construction, for example, archaeological discoveries at Beşiktaş station forced a major delay. Rather than halt progress, the agency and contractor restructured the signaling system and construction schedule to open the rest of the line in phases, minimizing delays and public disruption.

This adaptive mindset was matched by a commitment to learning and innovation. Initially, Istanbul relied heavily on foreign experts and supervisors, but local agencies, designers, and contractors quickly absorbed this knowledge, optimized their practices, expanded their equipment pools, and began investing in technologies like Building Information Modelling. This learning curve is evident across projects. One example is the Marmaray’s BC1 Bosphorus Crossing, undertaken by the Turkish Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, where the contractor, experts, and the agency tackled the engineering of a 190-foot-deep immersed tunnel beneath the Bosphorus strait, and found and managed archaeological discoveries at all four station sites — some dating back 8,000 years — through research, collaboration, and process refinement. From setting up concrete testing labs to adopting mixed-geology tunnel-boring machines and integrating archaeological oversight into construction planning, both public and private actors have continually adapted and improved their systems. By the time newer lines like M9 began, the city had developed a mature rail-building ecosystem. Even with an inexperienced contractor, the project stayed on track, thanks to the involvement of seasoned design and consultant teams and an institutional framework shaped by decades of continuous investment in urban rail.

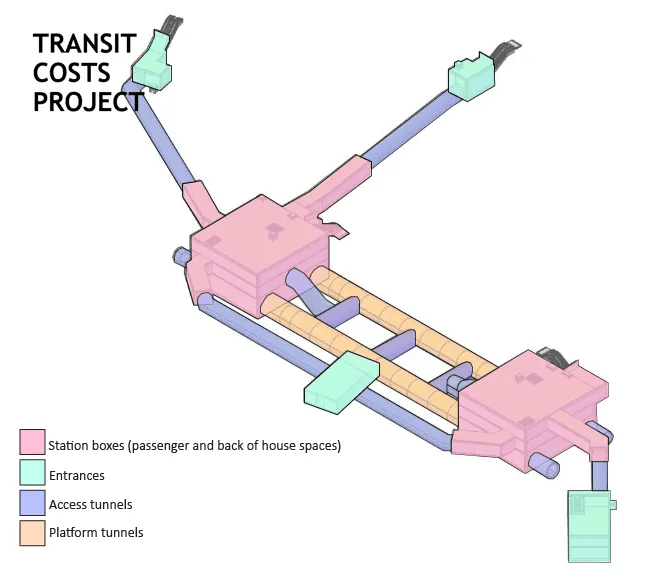

Another area where Istanbul has reduced costs through learning and innovation is station design, which is a major driver of rail construction expenses. Underground stations require large-scale excavation, land acquisition, and navigation of complex underground utilities. In early projects like M4, station designs were bespoke, with large mechanical spaces and extensive cut-and-cover construction. Over time, however, stations became more standardized. Starting with M5, key technical components like fan rooms were relocated from large dedicated mechanical spaces to more compact tunnels at the platform level, significantly reducing excavation volumes and cutting construction and land costs by tens of millions of dollars.

The early adoption and gradual integration of parametric 3D modeling through BIM further enabled designers to test typologies and streamline planning. While Istanbul builds long platforms to accommodate high passenger demand, it has prioritized cost control over architectural flourishes. Unlike cities that invest in signature station designs, Istanbul adopts a no-frills approach, choosing standardized finishes and simple materials to build more lines, faster and more affordably.

Istanbul’s experience demonstrates how standardized practices, institutional learning, flexible risk-sharing, and technology adoption can yield more efficient outcomes. Rail-building agencies should streamline not only station designs but also their project delivery pipelines. They should invest time and effort in the preliminary design and planning phases, avoid offloading risk onto consultants and contractors, and instead build strong in-house teams capable of managing risk and making informed decisions. To cultivate a healthier rail-building ecosystem, agencies should lower barriers for smaller firms by cutting unnecessary paperwork and bureaucracy. They should also reconsider oversized contingency budgets, which can inflate overall project costs. There is no single solution to cost reduction, but international examples offer clear, recurring lessons. When cities build rail faster and cheaper, they can expand transit networks more rapidly, advancing safe mobility, reducing car dependency, improving access to opportunities, and accelerating progress toward Vision Zero and a sustainable urban future.