It's the battle of who could care less — and safety is losing.

Buried in last week's report that officially confirmed the Department of Transportation's failure to meet legal benchmarks for bus- and bike-lane construction was this juicy tidbit:

Out of 51 City Council members, only six responded to a request from DOT Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez for recommended locations where street safety improvements should be made in their districts.

Rodriguez had sent the request after a Council oversight hearing at which Council members reiterated frequent complaints that the DOT either ignores their district or engages in top-down, one-size-fits-all bigfooting against local desires.

“Your suggestions ... will be a critical component of our data-driven planning efforts to achieve the laudable goals of 50 miles of protected bike lanes and 30 miles of protected bus lanes a year,” Rodriguez wrote at the time.

Despite the agency's apparent effort to listen to the electeds closest to the voters, Council members chose one of three responses:

- No

- Hell no!

- Not my job!

The "no's" came from lawmakers who have traditionally supported street safety projects and from some who have traditionally not supported street safety projects.

Council Member Gale Brewer (D-Upper West Side), for example, admitted through a spokesman that she did not respond — because her office has sent so many letters to DOT that have gotten no response.

The "hell no's" came from staunch opponents of the DOT's efforts to make roadways safer for cyclists. Council Minority Leader and bike lane opponent Joe Borelli (R-Staten Island), made his opinion about the agency's whole endeavor clear.

"Where is the box for suggestions on how to help drivers get from point A to point B in their cars," Borelli told DOT in an October email obtained by Streetsblog. "What is the point of this exercise if no one at DOT gave a fiddler's fart about the opinion of residents, elected officials, and community board in opposition to the recently installed Hylan Blvd bike lane."

Borelli's definition of DOT's mandate as one that focuses solely on drivers' experience begins at home, not at 55 Water St. According to the Census, Staten Island residents owned 216,422 cars in 2000. Just 20 years later, there are 248,370 cars on Staten Island, an increase of 15 percent.

In a call with Streetsblog, Borelli admitted that he has no interest in adding cycling lanes on the Rock. "If I get an email from DOT about a bike lane I don’t even open it up," he said, adding that he found Rodriguez's email "irrelevant because the problem with bike lanes is that they put them wherever they want without any significant input or need."

And though Borelli (and others) have long held that DOT ignores communities, that may be how the city's top elected officials want it. Council Speaker Adrienne Adams and Transportation Chair Selvena Brooks-Powers apparently did not offer suggestions to Rodriguez, saying through a spokesperson that picking corridors for bike and bus lanes is a job for city experts, not lawmakers.

"The law places responsibility for identifying bike and bus lane locations for the Streets Plan, and following through on them, with the administering agency, not lawmakers," said Mara Davis in a statement. "Redirecting responsibility for this work is inconsistent with the details and spirit of the law that DOT is tasked with implementing."

The result [PDF] of all this buck-passing, anger and apathy is clear: In 2023, the DOT built just 5.2 miles of protected bus lanes out of 30 miles required, and 32 miles of protected bike lanes out of 50 miles mandated by the Council's 2019 legislation.

Rodriguez's request for help came amid a year when cycling deaths were soaring, eventually reaching a horrifying 30 fatalities, and buses slowed back down to 8.05 miles per hour, the lowest speeds since the pandemic, according to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

DOT consistently blames Council apathy for its failure to meet legal benchmarks, citing “political challenges” that affect its work. “Often attempts to redesign streets are met with opposition from elected officials and community boards,” the latest report reads.

But it's also true that Mayor Adams cut agency spending by 5 percent and there was a considerable staff exodus during the pandemic, as Streetsblog previously reported. And the mayor has also set up an entirely new chain of command, led by the mayor’s chief adviser and opponent of street improvement projects Ingrid Lewis-Martin, to intervene in prominent cases, such as the Fordham Road bus upgrades in the Bronx, the McGuinness Boulevard road diet, and the Ashland Place protected bike lanes.

That new chain of command and a cityscape littered with stalled or canceled projects makes a mockery of Rodriguez's request for input on the ground since projects like McGuinness Boulevard had the backing of all the local elected officials, yet was still watered down by the mayor, who publicly mocked local Council Member Lincoln Restler in the process.

Disappointing. Despite previous commitment to build a better Bedford Ave, the corridor has dropped off the @NYC_DOT list, despite being in a priority Tier 1 area and requiring little else than flipping the location of existing bike lane and parking. What’s up, @OsseChi? pic.twitter.com/YoUdyeU4uv

— Mike Lydon (@MikeLydon) February 26, 2024

Another example is the long-awaited protected bike lanes on Bedford Avenue which mysteriously was missing among the “upcoming” street design projects DOT listed at the very end of its 108-page document — despite the agency presenting proposals last year and telling Bedford-Stuyvesant Council Member Chi Ossé that they plan to install the project this spring after delays.

In other words, advocates say, the mayor has to act, not use "community outreach" as either a requirement to act or a cudgel to dispense blame.

“For creating change and forging a safe, sustainable city, there’s no substitute for strong, decisive leadership from the top,” said Jon Orcutt, a former DOT official who now advocates with the organization Bike New York. "Trying to spread the blame for New York City’s shortcomings to local elected officials just shows how weak the city’s implementation game has become."

Other advocates blamed the majority of local electeds who didn’t bother suggesting specific locations to Rodriguez, but several of the lawmakers said the DOT questionnaire was just a distraction from the Adams administration's continued failings to roll out legally-required redesigns under the Streets Master Plan.

“City Hall is rightfully getting flack for delays and lack of vision, but Council Members are supposed to be our neighborhood champions, pushing local progress for New Yorkers,” said Sara Lind, co-executive director at Open Plans (which shares a parent company with Streetsblog). "And most of them actively ignored a direct request for projects that would make their constituents safer, happier, healthier, or less likely to be stuck on a super slow bus."

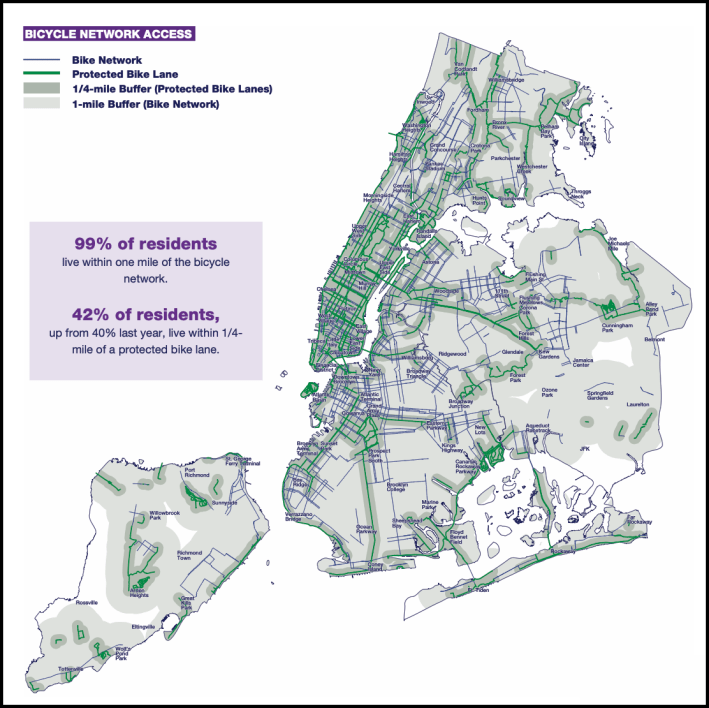

As a result, more than half of New Yorkers still don’t live within a quarter-mile of a protected bike lane, even as daily bike trips jumped to a record 610,000, according to the latest numbers from 2022. Meanwhile, DOT's plans in the pipeline for new bike lanes have slowed down to a trickle with 86 percent fewer project presentations in 2023 compared to the year before.

The latest report on the Streets Plan also had some specific bad news beyond the omission of Bedford Avenue:

Two projects in north Brooklyn — where powerful business interests like film studio company Broadway Stages have derailed projects — were also omitted from the list of future projects.

DOT had presented plans for bike lanes on Greenpoint's Kingsland Avenue and Monitor Street in 2022, and more preliminary community outreach from last year about improving Morgan Avenue, Metropolitan Avenue, and Grand Street in Williamsburg, but neither project was among the proposals the agency listed.

Agency spokesman Vin Barone claimed that the list of 129 proposals was just a summary of all the DOT's projects — despite the Streets Plan document not denoting that distinction — adding that the agency "continues to incorporate feedback" for Bedford Avenue.

Barone declined to confirm whether the project was still set to happen this spring, or what was happening with the two north Brooklyn redesigns.

"Bedford Avenue is a key north-south corridor in Brooklyn, and a protected bike lane upgrade will fill a key gap in the network and improve safety for everyone, whether you’re walking, biking or traveling by car," Barone said in a statement.

The agency press office also declined to reveal which six lawmakers responded to their queries.

DOT told Ossé that it would look into why the project was missing from the list, said Elijah Fox, a spokesperson for the pol, but officials didn't give the lawmaker an update either about when the protected lanes will go in.

The thing is: This kind of back-and-forth between the DOT and Council Members was exactly why the Streets Master Plan law was created — so that DOT would have a clear mandate to create safe streets for pedestrians and cyclists and clear roads for bus passengers.

“The goal was to provide a comprehensive, citywide network of protected bus and bike lanes, car-free pedestrian space, and more — without block-by-block fights,” said Elizabeth Adams, the deputy executive director of Transportation Alternatives. “The administration has a responsibility to meet the plan's mandates. We're two years into the plan, and we can't afford excuses and delays.”

Unfortunately, delays and excuses are on the agenda: Mayor Adams revealed last year that he doesn't consider himself bound by the legal mileage benchmarks of the Streets Plan, saying that he cares more about community feedback.

But where does that leave him when the feedback is a bunch of empty questionnaires?

— With Dave Colon

Clarification: After initial publication of this story, DOT spokesman Vin Barone claimed the section about agency budget cuts and staffing did not present a clear picture because "agency staffing has returned to pre-pandemic levels" and "DOT’s expense budget is $100 million higher today than it was during the last year of the previous administration, a roughly 10-percent increase."

We asked Barone how that jibes with these two paragraphs from the agency's own report:

Given fiscal challenges that hit NYC in 2023, serious actions were taken citywide, including a hiring freeze and a 5-percent Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEGs) in multiple Financial Plans. NYC DOT did our best to protect services, but unfortunately many programs, including supporting the Streets Plan had to be reduced.

Beyond the financial challenges, the limits of the City’s staffing capacity and facility space, and availability of materials and contracting resources continue to constrain the amount of work that can be done in a year, complex issues that money alone cannot solve."

Barone responded, "They can both be true," citing that staffing has returned from the pandemic "exodus" that our story mentioned and that the agency budget is higher than it was at the end of the de Blasio administration in 2021, despite the current mayor's cuts.