And they're suing us to stop congestion pricing?!

New Jersey's $11-billion plan to widen the Jersey Turnpike will dump hundreds more cars onto Canal Street an hour via the Holland Tunnel, according to a recent environmental review of the larger project, which will increase overall car use along the corridor by one-third.

The impending influx of more drivers to the region comes from expanding just the first half of the eight-mile turnpike extension between Newark Airport and the Hudson River tunnels, which the New Jersey Turnpike Authority plans to enlarge from four lanes to eight over the coming decades.

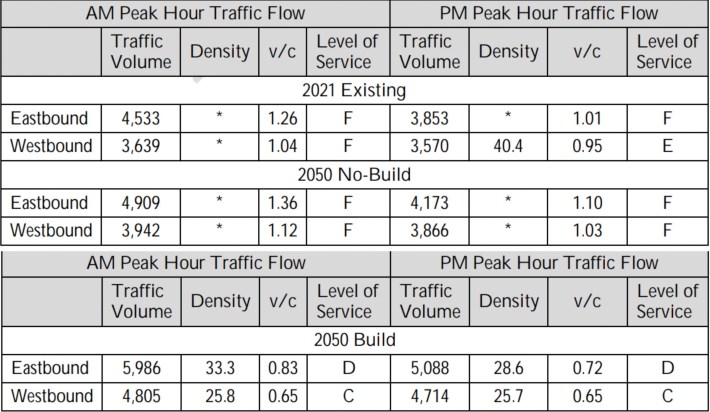

The bigger highway will draw 32 percent more traffic than today, which translates to an increase from 4,500 to 6,000 by 2050 heading east during peak morning rush hour, according to the figures in the 274-page environmental impact statement the Turnpike Authority released last month.

More than 1,200 of those cars will end up in Manhattan per hour in the morning peak.

The Garden State agency said it must expand the roadway to relieve congestion on its aging structure and meet a growing population. Without the widening, the study predicts a traffic volume increase of just 8 percent — evidence that the wider highway itself will induce demand for more automobile trips, many of which will lead into Manhattan.

The move comes as the city Department of Transportation is planning a redesign of Canal Street to make better use of that congestion sewer for the majority of people outside of cars. One pol representing the downtown area said the environmental statement from Jersey should be a "wake-up call" for the city.

"This would be disastrous for Lower Manhattan: our health, safety, and transit could all be severely worsened by this highway expansion plan," said Council Member Christopher Marte (D-Lower Manhattan). "It shows the urgent need for our city to step up and finally fix Canal Street, or else our thoroughfares will be used and abused by regressive transit plans from other states."

He said New Jersey drivers would "steamroll" New York City best-laid plans.

An $11-billion boondoggle

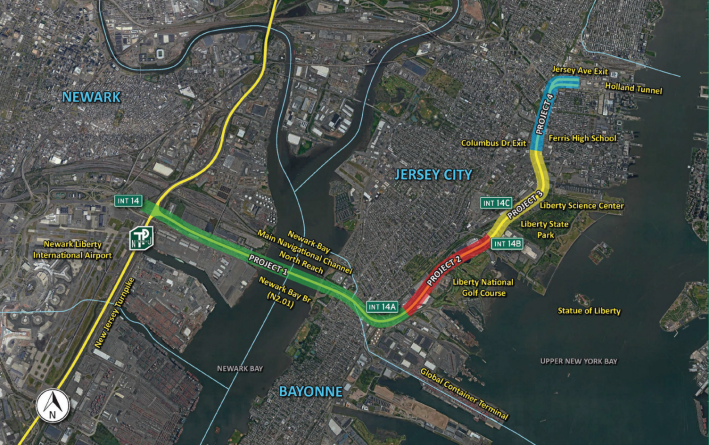

The lengthy review looked at the effects of widening just the first four miles of the Newark Bay-Hudson County Extension, an eight-mile offshoot from the mainline of the Turnpike, that links the roadway from Newark Airport to the Holland Tunnel.

The first $6.2-billion phase of the project includes replacing the 67-year-old Newark Bay Bridge between Newark and Bayonne with two new parallel spans, and New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy plans to continue building out more parts of the extension afterward for a whopping total cost of $10.7 billion.

Construction is set to start in 2026 and last about a decade for the initial portion, and the full project is still decades away from completion, but local advocates, politicians, and transportation experts urged Murphy to instead invest in the region's transit, as opposed to doubling down on automobile infrastructure.

“Increasing capacity when you have a tunnel that’s not going to be widened … makes little sense, sounds wasteful to me,” said "Gridlock" Sam Schwartz, who served as New York's Traffic Commissioner in the 1980s and remains an important consultant.

New Jersey drivers already swamp chunks of Manhattan in traffic for hours each day — especially near the Holland and Lincoln tunnels, truncating routes on MTA buses, and creating congestion on bustling thoroughfares downtown.

"It’s madness, they’ll never get through the tunnel," said longtime Soho resident David, who declined to give his last name, referring to the afternoon rush-hour traffic as all those inbound Manhattan cars get transformed to outbound cars. "It would be a dead stop."

The 45-year local of the area slammed officials from the state across the river for still relying on the 20th-century credo of highway expansions in 2023.

"It’s ridiculous, Jersey should spend the money on New Jersey Transit and provide better transit," he said. "I thought we were supposed to be moving away from automobiles."

Another local said that it would bring in more toll revenue, but also slow down his M55 bus.

"The issue is going to be gridlock," said Tribeca resident Robert Hampton.

Nevertheless, Jersey road officials justified the project, saying they needed to relieve congestion on the old highway, most of which consists of elevated structures like bridges and viaducts, while accommodating an estimated 170,000 new residents and 67,000 new jobs arriving along the corridor over the next decades.

Experts pushed back on the Robert Moses-style argument that the state needs to double down on automobile infrastructure to transport a growing population.

"I would say, 'Transit, transit, transit,'" said Schwartz. "The money would be much better spent on improving transit options, both in Jersey City and to Lower Manhattan. ... They have no shortage of good projects, this doesn’t sound like one of them."

The Authority's nearly 300-page environmental review did not look at public transportation alternatives, but a spokesman defended the project — and passed the buck.

“We’re a toll road agency. Decisions about building infrastructure for more sustainable modes of transportation are made by transit operators,” said Thomas Feeney in a statement. “The extension is being replaced with a facility designed to handle the future demands created by growth in the region.”

The Authority invests about a half a billion dollars a year in public transportation — nearly a quarter of its revenue — Feeney added, while contributing $124 million annually to the federal Gateway Program to build out commuter rail tunnels beneath the Hudson River.

Buried stats

The novel-length document examines the environmental effects of the western portion of the extension between exits 14 and 14A, dubbed Project 1, whose per-mile cost will net more than $1.5 billion, roughly the rate it cost to extend the 7 train to Hudson Yards in 2015. The funding for the project comes from Turnpike Authority revenue, 90 percent of which is from its tolls, according to officials.

Traffic on the section heading toward the Holland Tunnel will increase from 4,533 vehicles an hour in the peak morning rush hour in 2021 to 5,986 by 2050 with the wider lanes, up 1,453 cars, or 32 percent, according to the EIS.

Without the widening, officials estimate the numbers will still increase, but just to 4,909, and that's only up 376 vehicles, or 8 percent.

The percentage increases are buried 135 pages deep in the document, and were left out of a six-page summary of the environmental review, which merely cited "traffic growth."

Local officials along the corridor have come out in opposition and questioned the stated goal of relieving congestion, such as Jersey City's Mayor Steven Fulop, who told Streetsblog that the added traffic will merely impose more cars on his constituents.

"You’re only going to increase pollution and traffic on our streets here, and this is not a good solution," Fulop said. "The best solution would be to invest in mass transit and you would move people more quickly in and out of Jersey City and to the region."

Where do they get off?

How does this affect New York City?

Most of the vehicles on the Turnpike's extension get off before the Holland Tunnel via exits at Bayonne, Hoboken or Jersey City, with only 21 percent of traffic on the highway continuing toward Lower Manhattan via the underwater tubes, according to the Turnpike Authority.

The agency cited figures crunched by StreetLight Data, but did not provide the original numbers showing those rates, and the EIS does not have detailed data on where cars leave the extension.

Advocates opposed to the project have cited higher tunnel-bound rates from previous studies.

Mainly, they've referred to a previous 2020 needs assessment study with 2015 numbers indicating that 26 percent of total traffic in the morning rush on the extension left at the last exit at 12th Street, three blocks away from the tunnel. Another 32 percent got off at Columbus Drive, a common exit drivers use to cut through local streets and still get to the tunnel.

Feeney, the Turnpike Authority spokesman, said 59 percent of drivers getting off at 12th Street continue to the tunnel, along with 19 percent of tunnel-bound vehicles leaving earlier at Columbus Drive, citing the StreetLight figures. Those agency rates do indeed add up to 21 percent of the total Turnpike extension traffic, but without the original data to prove it, one opponent who crunched the 2020 study's numbers remained skeptical that the tunnel traffic wasn't larger.

"I think it's extremely suspect and hard to completely concede that, 'Yes the hidden data shows exactly what they hope to show,'" said Robert Howley, co-founder of the NJ Turnpike Trap Coalition. “Also, is it considered good that we'd be increasing nominal volume knowing 21 percent of it is headed to the tunnel which is obviously not getting any bigger? Is this supposed to be a point of relief?"

Using the Authority's 21-percent figure, the upstream highway widening would increase the share of cars going into New York City from 952 during peak rush between 7-8 a.m. to 1,257 — or an extra 305 cars coming into the city over just one hour, and most of those will likely commute back to the Garden State in the evening.

That could add hundreds of additional vehicles an hour to arteries like Canal Street, which is already heavily congested for much of the later afternoon and evening as drivers head back to the Garden State.

The Department of Transportation is wrapping up an eight-month study study this month on how Canal Street could be better for pedestrians, cyclists, and mass transit users, who account for the vast majority of people coming to the corridor to shop, eat, and visit friends — but have to share crowded sidewalks, while motorists get up to six lanes of space.

DOT spokesman Scott Gastel only said that the agency does not expect additional traffic in the morning, since tunnel capacity remains the same and the extra demand would queue up on the New Jersey side at that time, but the rep did not respond to repeated requests about the effects on the evening rush hour, when all those drivers are heading back home through the same tunnel.

Council Member Marte said the city must get moving on its improvements to the street, since New Jersey is already laying the groundwork for more roads on its side of the Hudson.

"Residents, workers, and visitors deserve a safer and greener way to cross Lower Manhattan. But so long as the City sits on its hands, we’re basically ceding our jurisdiction to outside authorities," Marte said. "I hope that the administration can use this as a wake up call for why my office and thousands of New Yorkers have been demanding a redesign of Canal Street, and finally put it into action."

Advocates also called on the officials in the region to focus on getting people out of cars and into more efficient mass transit.

"To fight climate change, leaders in our region must be doing more to reduce car dependency," said Juan Restrepo, director of organizing at Transportation Alternatives. "Instead of widening the New Jersey Turnpike, leaders should focus on getting trips out of cars by investing in transit and adding a second express bus lane to the Lincoln Tunnel."

"With congestion pricing coming soon, our focus must be on fixing Canal Street and giving space back to people walking, biking, and using transit," he added.

The Lincoln Tunnel has since 1970 provided a dedicated bus lane moving more than 70,000 passengers in 1,850 buses each weekday morning, and Howley, of the Turnpike Trap Coalition, suggested the Port Authority add a bus-only lane to the Holland Tunnel.

The Port Authority did not respond for comment on bus lanes in its tunnels.

'Muscular Infrastructure'

Gov. Murphy has long stood by the road widening project, saying the state needed "muscular infrastructure" to handle a growing population, but he has also fought efforts to reduce car commutes in the region.

Eight in 10 Jersey commuters rely on public transit to commute to Manhattan's central business district below 60th Street, according to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which plans to launch its congestion pricing charge covering that part of the island next year. A mere 3 percent use the Holland Tunnel to drive to that part of the Big Apple.

In July, Murphy sued the federal government over the congestion pricing proposal, citing concerns of extra traffic from drivers in his state detouring away from the river crossings to Manhattan, but he has dismissed concerns about all the extra cars that will end up in Manhattan caused by his own state's highway widening. Congestion pricing, supporters argue, is merely New York's effort to mitigate the damage caused by increasing car traffic from New Jersey and a failure of that state to adequately fund transit.

Murphy said in a WNYC interview in August 2022 that by time the project is built, there will be better transit in the region, such as the Gateway project to rebuild and expand cross-Hudson rail tunnels, along with better bus terminals.

"You’ll distribute the transportation reality, which right now is congested … and you’ll spread that out in a much more sensible way," he told the public radio station at the time.

Later that year, he implied that, even if there is more congestion, at least cars will be electric by then, so there would be less pollution from exhausts.

"We need new, more muscular infrastructure, and by the way, sooner than later that infrastructure will be carrying virtually all-electric vehicles," Murphy told a reporter during a press conference last December. "The infrastructure is not sufficient at the moment, so even if they were all gas cars, we need a better reality there and expanding the roads will make that a better reality — and then on top of that, it won’t be a lot of internal combustion engine cars sitting there and burning fuel."

We asked @GovMurphy about the Turnpike widening project in @JerseyCity. Judge his answers for yourself. (Remember it's a press conference, so know in advance that I didn't have time to ask the 15 follow ups you're yelling out loud right now.) Just watch & share. @NJSpotlightNews pic.twitter.com/pAChyQg9iV

— David Cruz (@DavidCruzNJ) December 22, 2022

Fulop, who is running to for governor in the 2025 elections — a year before construction on the Turnpike project is slated to start — told Streetsblog he would divert those funds to improving transit, such as extending the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail.

"We would take these dollars and better utilize them towards infrastructure that moves people around the state using mass transit," he said.

Murphy’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.