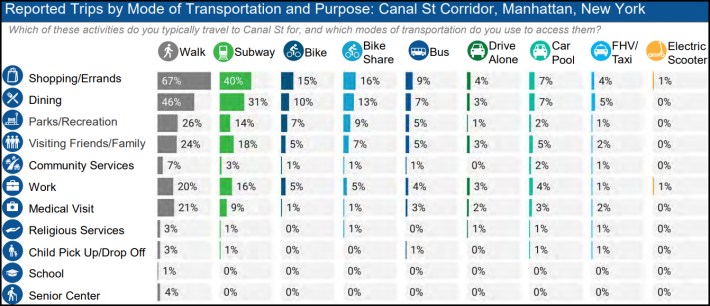

Barely anyone drives to Canal Street.

That's according to the city's latest survey of 480 shoppers, diners, tourists, workers and others on the busy Manhattan strip — which found just 4 percent of shoppers, 3 percent of restaurant-goers, 3 percent of people visiting friends or family, and 3 percent of workers got there by driving alone in a car.

Robert Moses never got to build the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway down Canal Street, but what New Yorkers got instead is only marginally better — wide lanes feeding car and truck traffic between the Holland Tunnel and Manhattan Bridge, sandwiched by two thin slices of pedestrians on narrow sidewalks bustling with vendors and tourists.

The chaos creates danger, mostly recently over the weekend when an SUV driver hopped the curb and collided with a traffic light and scaffolding at Canal and Broadway, according to Streetsblog contributor and local resident Joe Tedeschi. Since Jan. 1, 2022, there have been 274 reported crashes just on Canal west of the Manhattan Bridge. Those crashes injured 85 people, including 19 cyclists and 14 pedestrians, according to city stats compiled by Crashmapper. Previous Department of Transportation studies have identified the Canal as one of the most crash-prone corridors in the city.

Major accident at the always treacherous intersection of Canal and Broadway this morning. @StreetsblogNYC @StreetsPAC @ChrisMarteNYC pic.twitter.com/u8YrsDFPfC

— joseph (@jtedeschi1968) June 25, 2023

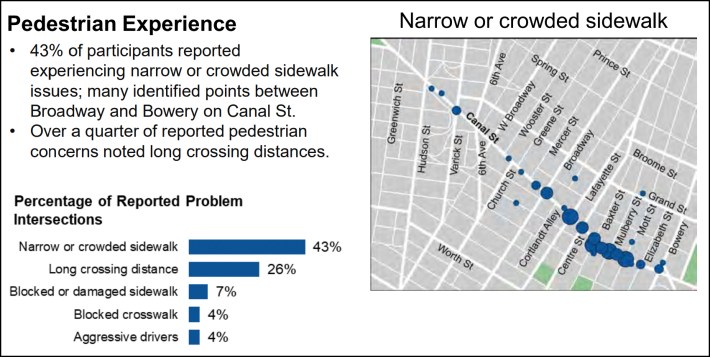

Canal Street between the Manhattan Bridge and Holland Tunnel is a designated truck route with as many as six lanes for cars on some segments. Pedestrians account for 64 percent of the people using the street, but cars and trucks take up 90 percent of the street at some locations, according to DOT.

Yet for virtually all purposes, the majority of people are getting to Canal on foot, on transit or on a bike.

Pedestrians who filled out the the agency's latest survey cited narrow sidewalks as the most "significant barrier" to safety on Canal Street, followed by drivers who don't yield to pedestrians and speeding.

The majority of cycling respondents, meanwhile, said they felt "very unsafe" riding bikes or micro-mobility devices in the area, the report said. Nearly three-fifths of all respondents — not just cyclists — expressed support for bike lanes in the area.

Surveyors also asked businesses where they most consistently observed double parking, which contributes to the area's chaos. Parking availability is clearly a problem on Canal Street — delivery workers using cars are more likely to park in front of a fire hydrant than in a legal space, the survey found. The more commercial-heavy blocks also had the most observed double-parking.

Bike lane skeptics will likely advice cyclists to ride elsewhere, but many of people people riding on Canal Street do so because their job requires it: A quarter of the businesses on the street make outgoing deliveries; 57 percent of those deliveries are made by bike.

That much is obvious to people who spoke to Streetsblog after the report's release on Monday.

"I see a lot of deliveries," said David, a waiter at the restaurant Chikarashi on Canal at Centre Street, who declined to give his last name. "They’re riding bikes or scooters on the road, and there are a lot of cars, so I feel like they should add some bike lanes."

DOT's survey is part of an eight-month study of Canal Street set to wrap up in November. The agency began outreach for the project over a year ago, and does not plan to propose any design changes until sometime next year — despite years of concerns about the dangerous, notorious "car sewer." A 2011 study previously recommended wider crosswalks and parking regulation changes, but avoided making more substantive changes like bike lanes.

Officials have said the current study will explore "multimodal improvements" and forecast potential impacts on auto traffic. Council Member Chris Marte told Streetsblog in January that he would like to see bike lanes and wider sidewalks, possibly along the median similar to Allen Street or Houston Street.

Congestion pricing, if implemented, could make a dent in the area's conditions by discouraging "toll shopping" drivers from taking the street to cross the East River for free via the Manhattan Bridge. That might make DOT traffic engineers more comfortable to make radical changes to the road's design, but the actual people who travel to Canal Street, as opposed to people who use it to get through Lower Manhattan, stand to benefit either way.

One 61-year-old cyclist said she'd resigned to putting her life at risk every time she rides through the area.

“I do this a lot, I’ve gotten used to it," said the bicyclist, who gave the name Annie. "Just because I feel OK, doesn’t mean I will be."

Additional reporting by Auden Oakes