For whom does this toll toll?

The MTA threw a wrench into the congestion pricing debate last week when it heavily cautioned against giving a congestion toll "credit" to drivers who enter Manhattan's Central Business District via already-tolled bridges and tunnels from New Jersey, Queens and Brooklyn.

State law requires the MTA raise $1 billion annually from the program, but the 2019 law does not dictate the dollar amount of the congestion toll, nor how much congestion it should alleviate.

Any discount or credit for one type of driver means other drivers will pay a higher “base toll” — closer to $23, officials said last week.

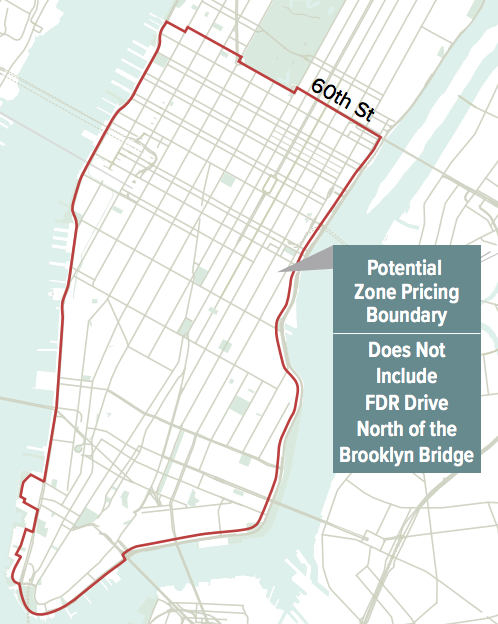

Every day, more than 1.2 million cars and trucks enter the future tolling zone — Manhattan below 60th Street. The MTA says that no matter what the toll eventually is, congestion inside the zone will drop by 15 to 20 percent — but traffic in other places may rise as drivers circumvent the Central Business District.

That might be a bit confusing, since congestion pricing was envisioned in part as a way to get cars and trucks off local street and bridges in order to create more space for buses, bikes and pedestrians. The MTA’s reluctance to give a break to these so-called “double tolled” drivers may threaten that goal.

Let "The Explainer" help you understand what's going on:

What is going on?

Right now, drivers have several ways to get directly into lower Manhattan: the four iconic (and free) East River bridges and four tolled tunnels: two controlled by the MTA (the Brooklyn-Battery and Queens-Midtown) and two controlled by the Port Authority (the Lincoln and Holland).

All those choices mean plenty of drivers are willing to endure some traffic and time to avoid paying a toll. That "toll shopping" forces neighborhoods around the free crossings — like Long Island City and downtown Brooklyn — to suffer externalities like pollution, crashes, congestion and endless honking,

But in the future — when the congestion pricing is finally up and running — entering lower Manhattan via the East River bridges will no longer be free.

That sets up a choice for the MTA: either give people credits for driving in through the tolled tunnels — which raises the "base toll" for everyone else entering on free bridges or simply by driving south of 60th Street — or make some routes into the CBD more expensive than others.

The choice isn't that simple, because if the already-tolled crossings cost more than the currently free crossings, many drivers will "shop" a lower price. And if the toll price is too high overall, the MTA believes some people will choose to drive all the way around Manhattan instead of through it — inundating outer-borough and suburban neighborhoods with traffic and its associated pitfalls.

Wait, will congestion pricing cause more traffic?

Well, the MTA certainly thinks there will be more congestion in some spots but not other spots. The issue is less that resentful car-lovers will grit their teeth and insist on piling up the miles, and more about how many drivers will avoid the new toll south of 60th Street by circumnavigating the area, a practice known as toll shopping.

What is toll shopping? Tell me this instant!

If no one gets toll credits, and the congestion pricing charge is say, $9, drivers coming from New Jersey would have to pay $14.75 to the Port Authority and $9 to the MTA, for a total of $23.75. It would be, in a sense, a "double toll" to enter the CBD, and some drivers would opt for a cheaper route.

"Think about it as shopping in the grocery store for a cheaper price on a similar item," said Regional Plan Association Vice President Tiffany-Ann Taylor. "If one store is selling something for $12 and another store is selling it for $20, and they're only two blocks apart, you're willing to walk the two blocks to get the same item for significantly less money. People make those same decisions when they drive, especially if a road that's going to get them to the same place is nearby minutes or a few miles away."

That thirst for deals will lead some drivers to go to great lengths to avoid paying tolls. In New York, this is common around the many East and Harlem river bridges, which provide un-tolled options for drivers who don't want to take the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, the Queens Midtown Tunnel or the Triborough Bridge.

Congestion pricing, in theory, should smooth this out by making it so that everyone pays the same, or nearly the same, to get into lower Manhattan. If tolls at any of the bridges and tunnels are significantly varied, people will opt for the cheaper toll, which will lead to more traffic around some bridges and tunnels than others.

In terms of impact, the largest predicted attempt at toll shopping will be drivers who choose the Triborough Bridge (which is already tolled) as a way to avoid lower Manhattan while getting to their destinations. If everyone is paying the same base toll, the MTA predicts 18,742 more drivers per day will take the bridge. But if drivers get credits for tunnels and bridges that are currently tolled, the agency predicts roughly 20,000 more drivers will shift to the Triborough Bridge every day.

Why? Because toll credits for some will lead to higher overall tolls for others, which would mean drivers would toll shop by avoiding Manhattan entirely.

"Those crossing credits ... would reduce toll shopping, but … would also increase the base toll rates, which in turn would encourage more vehicles to avoid the CBD and instead drive through other communities," said MTA Special Adviser Juliette Michaelson at a recent meeting of the Traffic Mobility Review Board.

What is the MTA doing?

The agency recently tossed a grenade into the debate around toll shopping at last week's meeting of the Traffic Mobility Review Board: According to the MTA's math, the cost of tunnel credits (and the end of toll shopping) would mean drivers who don't get credits for their bridge or tunnel would pay $9 more than drivers who do receive credits.

But the agency spun it this way:

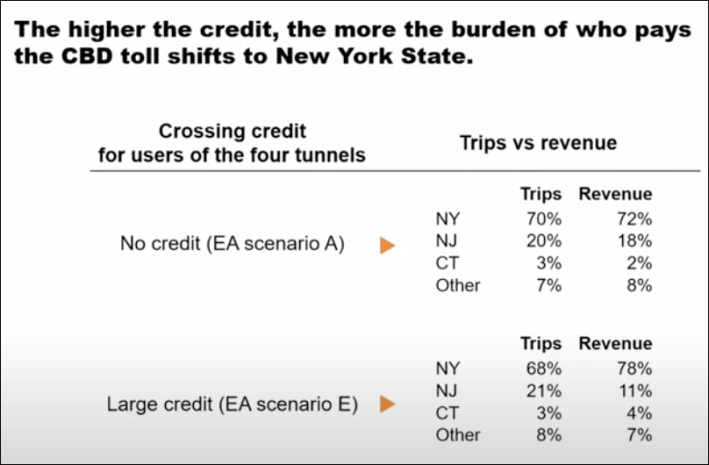

Giving out credits, according to the MTA, would create a huge shift in who pays for congestion pricing in terms of the share of revenue from New York drivers versus their equally loathsome counterparts from New Jersey, since the East River bridges would cost so much more.

Won't New Jersey freak out without credits?

Politics is an important factor here. New Jersey politicians have been moaning for years that their residents who drive to the city would be "double tolled" if they don't get full credits at the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels (not to mention the George Washington Bridge, though that span was not mentioned at a recent meeting of the TMRB). But if Jersey drivers don't pay both tolls, New York drivers have to make up the difference, according to the MTA. And, crucially, it's New York drivers who vote here.

"It’s all politics right now," said Bruce Schaller, who helped craft the congestion pricing proposal put forward under Mayor Michael Bloomberg. "If you overcharge the East River, you start to run the chance that the legislature will repeal the whole thing. It’ll be in the MTA’s mind."

The toll shopping challenge did not come out of left field. As you might remember, the MTA studied seven different toll policy scenarios for congestion pricing, scenarios that included varying levels of toll credits for different crossings. The fewer the credits, the lower the toll was, as seen in the chart below.

Buried in the environmental assessment, in the beginning of Chapter 4B, the MTA noted that among the seven tolling scenarios it studied, "higher overall CBD tolls under Tolling Scenarios D, E, and F would result in higher circumferential diversions compared to Tolling Scenarios A, B, C, and G, with lower CBD tolls."

That the credits would mean higher tolls for everyone else is something everyone agrees on. But the specific $9 increase for everyone else has its doubters. For instance transportation economist Charles Komanoff supports toll credits to cut down on the toll shopping, and said that his own model allowed him to come up with a $15 peak toll for everyone with full crossing credits and a $12 peak toll for everyone without crossing credits, meaning he worked out a way to raise the billion dollars with just a $3 price difference between credited or uncredited crossings.

Can we trust the MTA’s numbers?

Komanoff has argued that the MTA is overestimating the potential traffic impacts of the tolls on areas outside the Central Business District. MTA traffic models predict 72 to 82 percent of drivers diverted from the CBD will still opt to drive, but via other routes. That “flies in the face of common sense,” according to Komanoff, who argues instead that 25,000 vehicle trips will “disappear” — some in favor of transit, others by taking fewer total trips to avoid the toll.

The MTA’s modeling is not public, but Komanoff has said the difference from his own math is likely in how the transportation authority approaches “elasticity,” or how a new fee affects individuals' decisions to drive.

Schaller likened the effect of creating a new toll to items locked away at the drugstore. Faced with locked items at CVS or Walgreens, many customers will “just walk away.”

It “boggles the mind” that a large portion of drivers would opt for longer, more congested trips just to save money on tolls, he said.

“We’re talking about commercial traffic, their time is their money,” Schaller said. “Every dollar matters. There’s an elasticity attached to everybody, which means the first nickel matters the most. Just giving something a price will discourage some people.”

The MTA needs to show its work, said the RPA’s Taylor.

“It’s always important to ask for government transparency,” she said. “I don’t think it’s a matter of suspecting that there’s evil doings happening, I think it’s just a matter of understanding what is the math used to get to their calculations, so that … we can understand what they’re considering for their ultimate decision.”

Why do you keep putting 'double tolling' in quotes?

Well, it's kind of ridiculous that drivers think that paying one toll should excuse them from paying another.

For instance, drivers pay tolls at many points up and down the Garden State Parkway even though it's all one highway. And residents of Manhattan's West Side, who have been dealing with New Jersey drivers inundating their streets for decades, don't see congestion pricing as the same as the Lincoln or Holland tunnel tolls. For them, congestion pricing is about fairness for them, not for New Jersey drivers.

"[Congestion pricing] is not for crossing the rivers — the toll is for traveling on city streets inside the CBD," said Christine Berthet, the co-founder of CHEKPEDS, a Hells Kitchen pedestrian safety organization. "A New Jersey driver could pay the Lincoln Tunnel toll coming east across the Hudson, then take the West Side Highway and get to JFK without paying an additional dime. Only when this driver wants to use the streets within the CBD will they pay the congestion fee for using those specific streets."

And that's more than fair, Berthet added.

"New Jersey drivers use our streets as highways and are enraged that the tunnels are full of other New Jersey drivers who also want to return home," Berthet said. "They do not respect New York rules of the road and would never dream of leaving a pedestrian crossing clear to let a disabled person cross."

OK, but can we save the West Side from cars while still achieving congestion pricing's goals?

There's a few ways to look at it, all of which involve stupid amounts of waiting and a certain amount of fortunate breaks. For starters, there's Gateway! Please clap.

"It's worth reminding people that while this conversation is centered on congestion pricing, there are other major transportation projects happening in the region, like the construction of the Gateway program, and all of the projects related to commuter rail for that program between New York and New Jersey," said Taylor. "That's another way that we're able to get drivers off of the road."

But for once, there's more than just Gateway as an answer to New Jersey's transit issues. Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop cannonballed into the upcoming Garden State gubernatorial election with an initial focus on public transit and transportation. His agenda is ambitious, and includes creating a dedicated funding stream for the perpetually cash-strapped NJTransit, New Jersey absorbing the PATH system from the Port Authority, building out transit options in Bergen County and even congestion pricing Jersey-style (charging westbound tunnel tolls basically). The breadth of it could inspire his opponents to also think big about public transit and how much this dense region relies on it, and not just hype up electric cars. (Surely that will happen!)

Something like Gateway and better transit next door, combined with the system improvements the MTA can pay for with congestion pricing is the kind of thing that can create a virtuous cycle of reliable transit ---> increased ridership ---> fewer cars on the road ---> more funding for transit ---> reliable transit.

"As we see in other countries where there is more reliability of system service, folks become more comfortable writing in the system because they can see those improvements. I think that also lends an opportunity for us here in the New York and New Jersey area, as we're talking about congestion pricing," said Taylor.

And if after all that, people insist on driving, we can toll the hell out of them.

OK, so double-tolling is fake, and Jersey drivers have gotten away with it for too long. Screw 'em!

Well...

Come on!

It's more complicated than that. Because if you do charge everyone the same $9 congestion pricing toll, Jersey drivers aren't the only ones taking it on the chin. Someone coming in through the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel or Queens-Midtown Tunnel would pay $16 (the congestion pricing charge plus $7 for the existing tolls), which would mean either they're paying almost double the price of someone coming over an East River bridge or ...

...they'll just toll shop on one of those bridges, leading to more traffic in neighborhoods around those tunnels?

Yes, exactly. So you can see how this is difficult. Also while the West Siders have valid grievances, longtime congestion pricing supporters say that if everyone is getting a benefit from congestion pricing, everyone should have to pay the same price to get to the congestion pricing zone.

"I think that if we're all using the same infrastructure and getting the same benefits out of it, there is an opportunity to make sure that we're contributing equally as much as possible," said Taylor.

Interestingly, if you're someone looking at congestion pricing as a way to clear off the East River bridges and better balance the uses of those bridges away from cars and more towards cyclists and pedestrians, you should also be in favor of crossing credits, according to the environmental assessment.

Damn, you read the entire environmental assessment?!

We would do it even if it wasn't our job. That's who we are.