Everyone in the livable streets movement wants congestion pricing to start on schedule in May. But the many brilliant minds in the movement often have different approaches to reducing the political tensions that a new toll creates. Streetsblog recently published an article citing MTA data that suggested that congestion pricing credits for existing tunnel users might increase resentment of some New York City drivers and, eventually, their political enablers who don't really support congestion pricing and are looking for any excuse to kill it. But leading expert Charles Komanoff has a different view. So let's hear what he has to say.

The Editors

No one said that setting the right prices for congestion pricing would be easy. But after listening to the MTA officials’ dire pronouncements about tunnel toll exemptions at last Thursday’s meeting of the toll-setting Traffic Mobility Review Board, I couldn't help but think, "It shouldn't be this hard."

To review: A senior member of the MTA’s congestion pricing team warned that exempting car trips made to Manhattan via the already-tolled Hudson and East River tunnels could require sticking other zone-bound drivers with an additional $9 congestion tab to ensure meeting congestion pricing’s billion dollar a year revenue mandate.

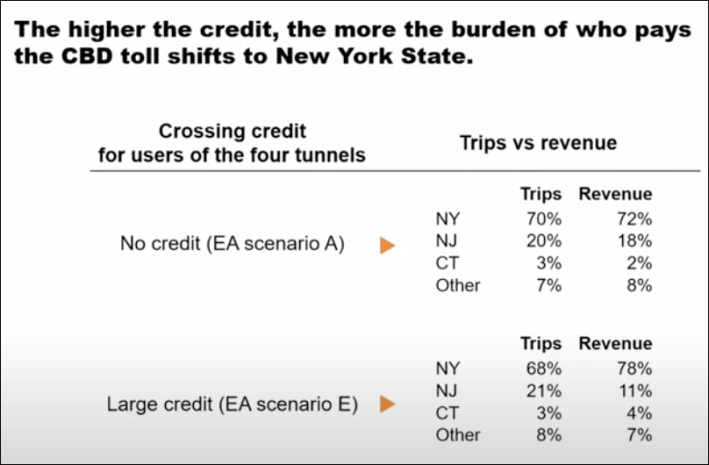

But that $9 figure appears wildly inflated, perhaps by three-fold (I’ll get to that in a second). But the shadow cast by that new dose of sticker-shock was scary enough to pique the interest of Streetsblog, which emblazoned its story the next morning, Congestion Pricing Tunnel Credits Would Help New Jersey Drivers Over New Yorkers.

There’s a lot to unpack here. Let's start with something we can all agree on: if drivers using the tunnels weren't already tolled, they should face the same congestion tolls as drivers coming in across 60th Street and via the four East River bridges.

Except the tunnels are tolled. Drivers using the two Hudson River tunnels now pay the Port Authority $14.75 during peak hours and $12.50 off-peak. Effective this Sunday, drivers using the two East River tunnels will pay the MTA a shade under $7 in each direction (up from $6.55 currently).

A look at actual traffic volumes shows that revenue from tunnel double-tolling ― adding the congestion toll on top of the existing tunnel tolls ― isn’t critical to congestion pricing’s success.

From 2021 traffic volumes, the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels account for just 14.6 percent of vehicle trips into the congestion zone. The MTA’s Queens-Midtown and Brooklyn Battery Tunnels account for another 12.8 percent, so the four tunnels combined constitute only 27-28 percent of total potential congestion revenues. Those figures are more than beanbag, but they’re not vital to congestion pricing’s success.

The hypothetical take from double-tolling the MTA tunnels is a helpful, but unessential $130 to $150 million a year, and $170 to $200 million for the Port Authority tunnels. Giving up those toll revenues just doesn’t qualify as a season-extinguishing event like the injuries to Yankees slugger Aaron Judge or Mets closer Edwin Diaz.

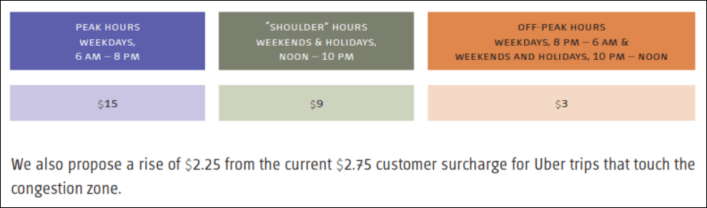

Columbia Business School climate economist Gernot Wagner and I didn’t need those monies to fashion our 15-9-3 toll plan, where we showed that congestion pricing’s $1-billion-a-year revenue requirement can be satisfied without double-tolling the tunnels while capping peak tolls at $15.

But the case against tunnel double-tolling isn’t just about money. I believe that crediting the existing tunnel tolls against the new congestion toll is vital if congestion pricing is to realize its full potential as a world-changing, city-revitalizing policy.

Look at the reverse: Charging inbound Holland and Lincoln peak trips 30 bucks ($14.75 for the tunnel toll plus $15 for the congestion pricing toll) when other peak entrants to the congestion zone will only pay the new $15 fee is patently unfair and, worse, would lend a patina of reasonableness to New Jersey politicians’ anti-toll posturing and possibly bolster Gov. Phil Murphy’s insidious anti-toll lawsuit, which threatens to delay congestion pricing’s startup beyond next spring.

As for the Queens Midtown and Hugh Carey (formerly Brooklyn-Battery) tunnels, double-tolling them would maintain the $7 price differential between the East River tunnel crossings and the bridges, perpetuating the toll-shopping that blights neighborhoods on both sides of the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg and Queensboro bridges.

There’s more. Unfairly or not, double-tolling would corroborate the canard that New York congestion pricing is just a money-grab. For decades to come, the apparition of a $30 congestion toll would haunt other congestion pricing proposals, just when urban and climate advocates from Delhi to Denver are looking to them to check city- and climate-destroying dependence on private cars.

Considerations like these are why every prominent New York congestion pricing proponent has called on the TMRB to credit existing tolls on the four tunnel crossings to the congestion zone. “Gridlock” Sam Schwartz made tunnel credits a centerpiece of his Daily News editorial last week; so did the Congestion Pricing Now coalition comprising the Regional Plan Association, the Riders Alliance and dozens of allied organizations in their July letter to the TMRB.

As for Gernot’s and my 15-9-3 toll plan: Using my BTA spreadsheet model (18 MB Excel sheet), we found that charging a peak-period car toll of $15 during 6 a.m.-8 p.m. weekdays, along with $3 off-peak (8 p.m.-6 a.m. weekdays and 10 p.m.-noon weekends) and a $9 “shoulder” charge at other times, bolstered by a new $2.25 surcharge on zone-touching Uber and Lyft (but not taxi) trips, will generate annual gross revenues of $1.34 billion. After netting the estimated $110 million a year for toll administration, our kitty stands at $1.23 billion, well in excess of the $1 billion a year required to bond the mandated $15 billion in congestion revenue-supported transit capital improvements.

MTA staff have toiled for years to shepherd congestion pricing almost to the finish line. Watching the authority’s Juliette Michelson and others at Thursday’s TMRB meeting brought home their work assembling and curating their prodigious Environmental Assessment and now fielding endless questions from elected officials and citizens. The team deserves praise for their poise in the face of constant nitpicks and pinpricks.

That said, something seems unduly doomsday-ish with the MTA’s congestion pricing modeling. I said so last fall, amid the fallout from the EA’s failure to register the inevitable drop in car commuting to Manhattan from Westchester and its benefits for the South Bronx and other environmental justice communities. The same must be said today about Thursday’s dubious claim that fully crediting the tunnel tolls would force all other drivers to the zone to pay as much as $9 more in their congestion charge.

To test that claim, I ran the BTA with a bunch of toll combinations that generated the same net, $1.23 billion a year, as Gernot’s and my 15-9-3 plan, but with the MTA’s Thursday scenario of double-tolling all four tunnels. One easy-to-remember result was 12-6-2. Translated: Tolling private cars $12 peak, $6 shoulder and $2 off-peak while double-tolling the four Hudson and East River tunnels generates the same revenue as our $15-$9-$3 peak-shoulder-off-peak tolls with full tunnel toll credits.

Voila, tunnel credits will “cost” other zone trips, if you want to put it that way, an extra $3, not $9.

Gernot and I regard 15-9-3 with tunnel credits as better politics and sounder policy than 12-6-2 without. We suspect Sam Schwartz and our many other congestion pricing partners would agree. You, dear reader ― and, perhaps, TMRB member ― may prefer 12-6-2 with tunnel double-tolling. Whatever your opinion, let’s please debate that choice based on dollar realities, not nightmares.