It's like a greatest hits album of MTA financial gloom.

State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli says that the regional transit agency is facing a $2.5-billion annual operating deficit in 2025 — and more in the "out" years — if it does not restore ridership to pre-pandemic levels that no one thinks is possible.

His findings mirror those of other watchdogs, as well as the agency itself, which projected in July that it will lose almost $4 billion in expected fare revenue through 2026. DiNapoli's numbers suggest that number is closer to $4.6 billion.

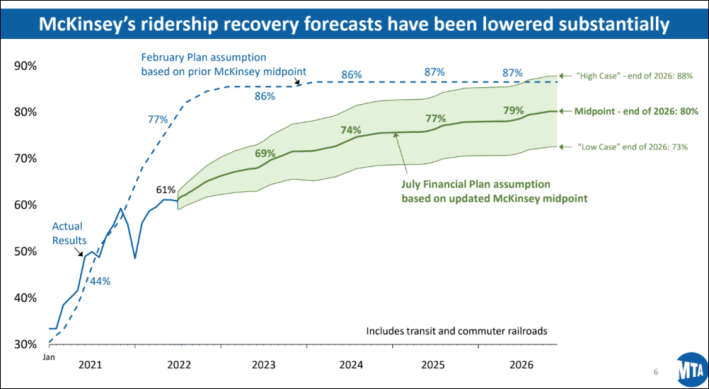

Citing the MTA's worst-case scenario ridership projections — only 73 percent of 2019 ridership returning by 2026 — DiNapoli concluded that the fare revenue on which the agency survives would be down by $350 million. Even the best-case scenario calls for 88 percent of ridership to return, which would still leave a budget hole in the hundreds of millions.

Other financial storm clouds have been previously documented. For example:

- Inflation is no friend of anyone. Every 1-percent increase in inflation over the agency's 2-percent budget assumption raises costs by $150 million annually, DiNapoli said.

- The comptroller also noted what the MTA itself has observed: a recession could reduce tax revenues that also underwrite transit by $500 million to $1 billion (not to mention depress ridership again).

- The agency's pension costs may rise "based on actual returns compared to assumptions" because the stock market — in which the pension fund invests its workers' contributions — is down down down right now. (For a scare DiNapoli reminded readers that the pension system "assumes a 7-percent return on investment and reported an 8.39-percent loss in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022" (emphasis ours).

- Congestion pricing is great news, but the agency can't use that money for day-to-day operating expenses, lest it undermine its crucial long-term construction and repair jobs.

- The MTA has started talking up the idea of getting new funding streams, which, if successful would free up the agency "to use $3.5 billion of the federal funding to pre-pay debt [and] save $3.9 billion during the 2023 through 2028 period avoid the long-term cost of deficit borrowing which would save $938 million between 2024 and 2028," DiNapoli wrote. (In its famed "fiscal cliff" presentation from July, the MTA said it would pay down some debt if its able to get a new revenue source and not have to spend all the federal aid.)

"The MTA’s projected budget gaps in 2025 and 2026 are substantial, exceeding 14 percent of combined operating revenues, taxes and other subsidies," DiNapoli said, adding that the agency is probably "understating the size" of that structural deficit.

The trouble is on the horizon rather than in the near view because federal funding provided a stopgap during the pandemic. But that money is running out a bit faster than originally projected (again because ridership remains so sluggish).

All eyes are, as always, on ridership.

"The Comptroller's office is rightly noting that while the goalpost has changed for ridership — 69 to 80 percent of where we were in 2019 — and we should be concerned about how worse it will be for the MTA if they can't even make these new goals," said Rachael Fauss of Reinvent Albany.

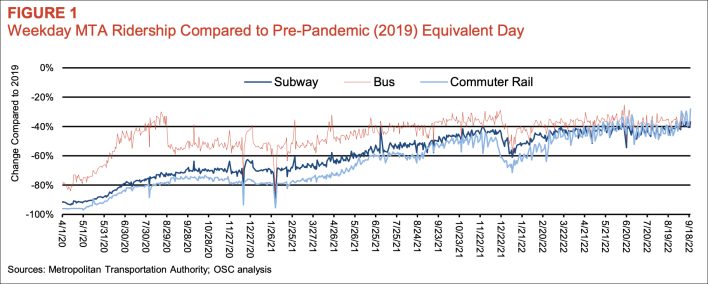

And don't mistake all the "post-pandemic record ridership" hype for actual success in luring back riders, Fauss added, pointing out that on Tuesday, for example, total subway ridership was 59.2 percent of a typical pre-pandemic day. And that day was no outlier. On any given weekday, ridership underground is roughly 60 percent of what it was during the "good" old days before a virus messed with so many best-laid plans.

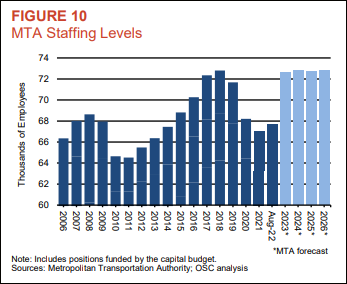

The report also had a bit of an irony to it. Since the pandemic, MTA staffing levels have been roughly four million workers off the 2018 peak (see graphic). As a result, service has suffered, which is another reason why riders have not returned, DiNapoli suggested.

"The MTA’s [understaffing has] led to service delays," he wrote. "A high number of subway trips continue to be canceled because of the lack of worker availability. ... If lower service levels continue, they could hinder the region’s recovery from the pandemic." (DiNapoli's report mentions subway cancelations, but didn't mention buses that simply don't make their runs, which happens, too, the Daily News reported.)

But Fauss said the MTA's forecasted staffing restorations appear too optimistic.

"The staffing projections show pretty big jumps," she said. "It will be very hard for MTA to ramp up this quickly."

DiNapoli's report is short on recommendations, serving more to diagnose the disease rather than treat the symptoms.

"The MTA needs to come up with billions of dollars to pay for operations in the coming years," DiNapoli said in a statement. "This has to be achieved against broad economic challenges that are increasing costs and threaten a recession."

The MTA did not answer specific questions put forth by Streetsblog but the agency's chief of external relations John McCarthy issued the following statement:

“This report is consistent with what we have come to understand since the pandemic started: mass transit is an essential service for New Yorkers. We agree with the Comptroller’s findings, and the MTA has begun working with decision makers to develop a plan that assures continued strong mass transit service in the post-COVID era. We are also aggressively pursuing long-term savings and efficiencies while providing transit services to millions of riders that power the region’s economy.”

It's nice that the MTA agrees with DiNapoli's findings, but advocates need more than camaraderie.

"The burden is on New York's governor, who controls the MTA and presents the state budget, to bring back riders and rebuild revenue by investing in more frequent public transit service," said Riders Alliance Policy & Communications Director Danny Pearlstein. "Maintaining the MTA's indispensable role of running buses and trains for several million New Yorkers demands that the governor provide new state funding and more frequent service.

"The comptroller is right that the MTA needs billions of dollars to pay for operations; it's the governor who must answer, investing in stability and growth with more frequent service," he added.

Want to read the report for yourself? Scroll below.