Don't trash the Bronx.

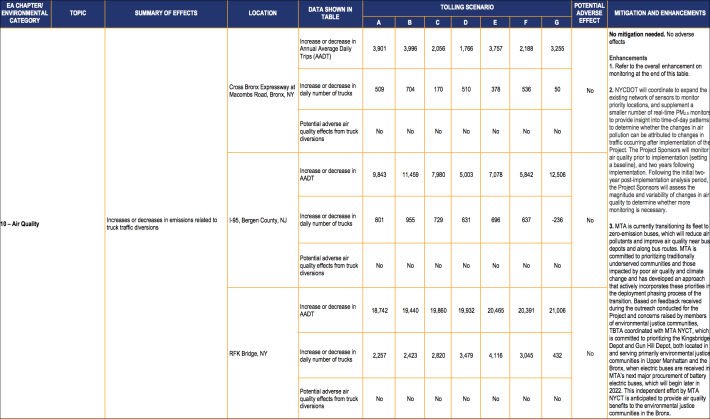

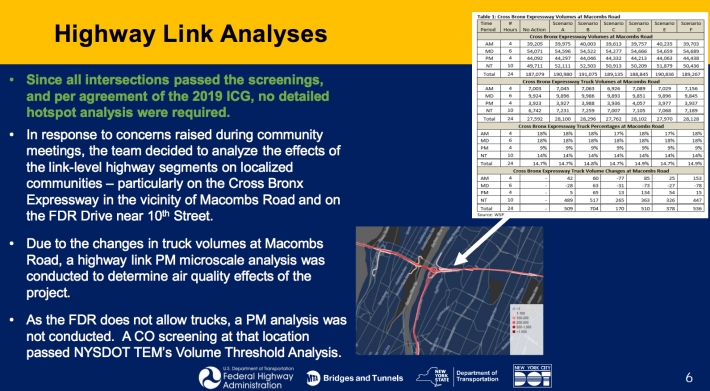

Elected officials and advocates are keeping their eyes on a potential downside of congestion pricing, an increase in traffic on the already polluted and gridlocked Cross Bronx Expressway, one of the spillover effects the MTA's congestion pricing environmental assessment identified if New York institutes a toll to drive through lower Manhattan.

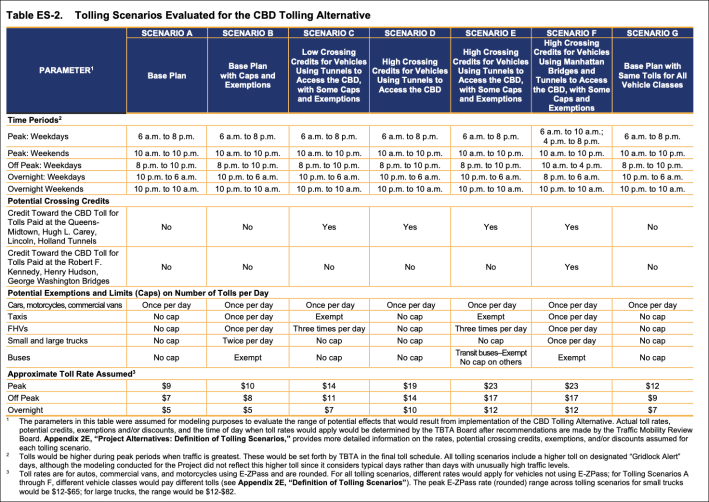

Each of the studied seven tolling scenarios showed that the massive overall benefits across the New York City region from reduced vehicle miles traveled and $1 billion for transit repairs does come with some adverse effects: the Cross Bronx Expressway will experience an increase in truck traffic from drivers avoiding the toll they would pay if they cut through Manhattan.

Overall traffic through the area was predicted to increase by 1,766 to 3,996 daily vehicle trips on average, depending on the toll price and combinations of credits and exemptions. The above increase includes 50 to 704 daily truck trips through the area (though the higher figure comes from Scenario B, which doesn't raise the required $1 billion so will not likely be the final toll schedule).

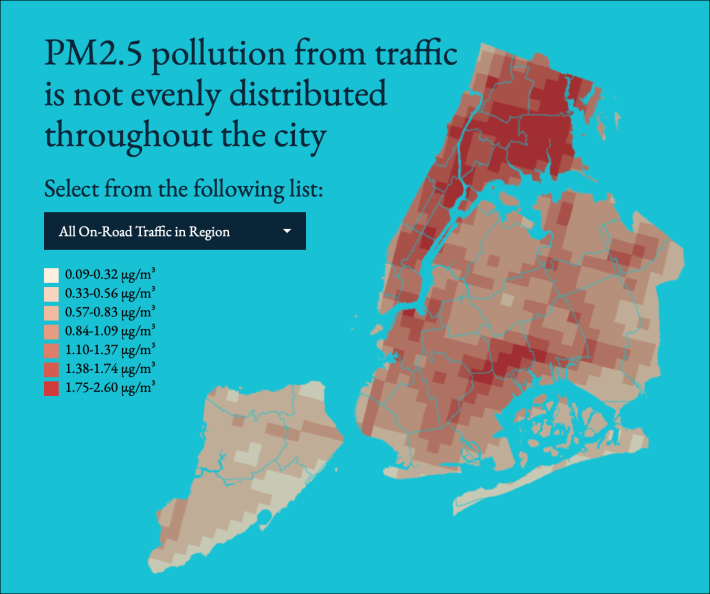

Now, is that a lot? In a city where fine particulate matter that is linked to truck traffic is already responsible for hundreds of premature deaths per year, any increase in pollution is an issue. And as the map below shows, The Bronx is already shouldering more than its fair share:

But 170-700 additional trucks is not very much, given that without congestion pricing, there will still be an estimated 27,592 trucks passing the sample location in the environmental assessment. In other words, the increase in truck traffic even under the worst-case scenario amounts to a 2.5-percent increase in trucks.

The MTA estimates a total increase in car and truck traffic to max out at 3,996, which would be a 2.1-percent increase — and according to the agency, the amount of pollution produced by those additional vehicles still meets National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

Still leaders in the Boogie Down, including those who support congestion pricing, aren't eager to see their borough dumped on again.

"Truthfully, I don't think we can afford to have any more trucks on [the Cross Bronx]," said Bronx Council Member Amanda Farias, who represents a district near the Throgs Neck and Whitestone bridges. "We know that people are going to be rerouted regardless if its cars and trucks because of congestion pricing, and I support it in principle. But it's necessary for the city not to put another burden on the Bronx."

Farias said that the predicted increase in truck and vehicle traffic should give more urgency to federally funded effort to cap or otherwise reimagine the Cross Bronx, a project that's not slated to offer up solutions until 2024 at the earliest.

Advocates for congestion pricing said that the slight increase in truck traffic in the Bronx should not sink the entire program but simply that the environmental assessment puts the onus on the city, state and feds to solve the problem.

"There are overall beneifts for folks throughout the congestion pricing catchment area," said Tri-State Transportation Campaign Executive Director Renae Reynolds. "They include better, more efficient public transportation once get cars off the road. But we can't ignore the challenges, and there should be assurance that there are solutions that mitigate those burdens. And transit advoates will be part of the drumbeat that environmental justice communities are not sacrifice zones.

"I can't say this more emphatically: this has to be a collaborative process," Reynolds added. "Not all of this is in the purview of the MTA. It's going to take some cross-collaboration. Everyone is still doing their analyses, and we'll need collaboration from the local and state and federal levels of government and from the scientific community."

In the same way that Farias wants an added urgency to solutions for fixing the the Cross Bronx, Reynolds said that congestion pricing is an opportunity to speed up state and private industry efforts to reduce transportation emissions as part of the state's overall requirements to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2040.

"As many of the vehicles the city is administering, those should be clean vehicles. If there are other incentives for private truck owners, efforts to engage with big hubs in the south Bronx, to turn over those fleets, every tool at heir disposal should be utilized. It's going to take some incentives for private owners and operators to electrify their fleets, we need mandates from the state to encourage that. Everyone has a piece of the puzzle, from Amazon and UPS to food distribution centers in Hunts Point, everyone has to think about how to center environmental justice and equity and reduce our carbon footprint," she said.

Reynolds also said that the city had to "remember our rail lines and the power of freight" as a solution to get trucks off the road, which is a solution that the MTA is trying to balance with its stated goal of returning passenger train service between Bay Ridge and Jackson Heights as part of the Interborough Express.

The MTA, through the work of the Traffic Mobility Review Board, does have an opportunity to mitigate some of the predicted effects from drivers trying to avoid the toll. As the TMRB does its work to recommend the toll structure, it could do well to look at the scenario that tolls every vehicle the same, which removes the incentive for truck drivers to go out of their way to avoid a toll that, in other scenarios, could be as high as $82.

But when every vehicle is charged the same amount of money, only 50 additional trucks per day are predicted on the Cross Bronx. There's also a possibility of a toll that offers small credits for drivers going through tunnels into Manhattan and also keeps the price relatively low, which results in a smaller number of trucks and general traffic diverting through the Bronx.

For Farias, the more the city and the MTA can do to move cars and trucks off of the Cross Bronx, the more she said she can talk about what congestion pricing is supposed to do.

"I want to ease that traffic, ease that congestion, so that the cars and the trucks that are needed to cross through for essential and necessary transportation are able to use the [Cross Bronx], so we can promote what congestion pricing does in principle promoting folks to use mass transit," she said.