"Them that's got shall get," an old song goes.

An entitled new interest group — wealthy Manhattanites — is seeking exemptions from future congestion-pricing tolls, and their elected officials are carrying their water.

State Senator Brad Hoylman and Assembly Member Harvey Epstein, who represent Manhattan south of 60th Street, aka the Central Business District, are proposing a bill with exemptions for residents who make 120 percent of New York's area median income. The exemptions would mean that a single person making as much as $100,320 a year or a four-member family making as much as $143,600 a year could pass the costs of driving — in dollars and pollution — onto the on-average-much-poorer rest of us.

The legislators, who made the case for the regressive exemptions during a public meeting conducted last week as part of the environmental assessment of the policy, called the matter one of basic fairness.

"People who are working class and middle class who are living in the zone but need their cars, like people who are musicians who have gigs outside New York City and have to bring their music equipment with them, those people who have to drive are being forced to pay when they come home," Epstein told Streetsblog. "These are people who are working New Yorkers and working-class New Yorkers who, because of where they live, and because of their profession, are going to be stuck with paying a tremendous cost, which would make it next impossible for some of these artists to continue to survive and live in our community."

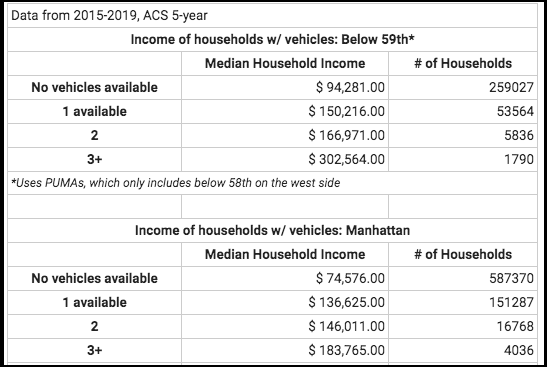

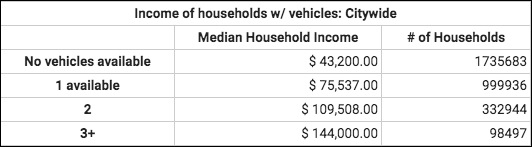

Not really. The exemptions would tend to help a relatively well-off group. According to the American Community Survey, from 2015 to 2019, Manhattan CBD households owning a vehicle had more than twice the annual median income ($150,216) than did those without a car ($74,576). Those with more income tended to own more vehicles.

Across the city, in fact, car-owning households had median incomes much higher than households without vehicles.

In other words, Hoylman and Epstein are proposing to exempt residents who, on average, are much wealthier than the rest of the city — undermining the entire program, which must raise $1 billion a year for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The New York law establishing congestion pricing already gives tax credits equal to the tolls to CBD residents with incomes of less than $60,000 a year. Any shortfall means that each discount must be made up elsewhere.

"This is a situation where, for whatever reasons, someone is advocating, ‘Oh there should be an exemption for this and a credit for that,’" said Citizens Budget Commission Vice President of Research Alex Heil. "If you have a fixed revenue goal, the fee for everybody else is going to be high. You're pushing down on one side is going to move up on the other side."

A resident discount or exemption isn't unknown in other congestion-pricing systems. In London, for example, residents of the (much smaller) congestion zone receive a 90 percent discount. But London's congestion-pricing program doesn't have a fixed revenue target attached to it, as New York's does, which means that the discount doesn't cost other people anything outside of the usual negative consequences of driving (such as congestion, pollution and road deaths).

Longtime congestion-pricing expert Charles Komanoff pointed out that "everyone who drives has a rationalization to be excused from the toll ... but none of them can make an argument that their trip by car doesn't delay others."

In a recent Streetsblog analysis, Komanoff noted that just the inbound leg of a single CBD car trip costs other road users about $50 worth of aggregate delays.

Hoylman said that his bill is a signal flare to the Traffic Mobility Review Board, the body that will determine the price of the congestion-pricing tolls, to press it to explore more exemptions than those that were written into the law.

"It's a way to raise the concerns about those folks who make more than $60,000 and might depend on their vehicles at this point," he said, saying that discounts or exemptions should be phased out once people had "time to adjust to this very different way of conducting one's life."

The MTA has said that it's exploring different scenarios with exemptions that could result in tolls of anywhere between $9 and $23, depending on who gets out of paying the toll. Komanoff, who's used his Balanced Transportation Analyzer to explore various effects of congestion pricing on the region, determined in 2020 that a total exemption for Manhattan residents in the CBD would drive up toll prices by 10 percent for everyone else.

Congestion pricing doesn't just function as a price on driving into Manhattan. The toll is also supposed to price the societal costs of driving, such as air pollution and time lost to congestion. Something to keep in mind when, say, the New York Post profiles families in Manhattan who say they're being unfairly singled out for a tax even as asthmatic children across the city breathe in particulates from car exhaust.

"When an asthmatic child inhales particulate emission, the particulates don't inform the the asthmatic person of what the income of the emitter was," said Alex Armlovich, an urban economist at the Citizens Budget Commission. "This is a price on a bad thing. There's a real cost that occurs [from driving] and so putting a price on that is about putting a price on a real thing. Politicking around it doesn't change the underlying real thing that happens."

Some Manhattanites, of course, get it. At a recent public comment meeting, resident Carl Mahaney pointed out that the tolling plan is essential for life on the island:

Calling this area a “business district” is a gross mischaracterization. For us it is a living district, more than 1.3 million New Yorkers lives in this area and millions of others walk, bike or take transit to work and go to school here. We breathe the air here we raise our families here, we live our lives here," he said. "However, what we have with the status quo is hostility and aggression, noise and air pollution, and the constant physical and psychological threat of violence, thanks to unimpeded vehicle traffic on our streets. That has to end. Those who choose to drive into and through our neighborhoods, would likely never accept these same conditions in theirs. In fact, I imagine they would try to do something to fix it. And that’s what congestion pricing does."