The battle over congestion pricing exemptions is coming — but the facts and the law are on the side of mass transit.

On Wednesday evening, PIX 11 released a clip of a wide-ranging interview with Eric Adams, in which the likely mayor-to-be voiced his opinion on who should be exempt from congestion pricing, whenever it is implemented.

"We should, number one, make sure that we are not harming low income New Yorkers that must go into Manhattan. Such as, if you have to go into Manhattan, low income, for chemo treatment. You're not doing it because it's a luxury," Adams told reporter Dan Mannarino. "The goal is to get the vehicles off the road where people are using it as a luxury, not necessity, particularly those who are dealing with economic challenges."

As Adams demonstrates, determining whether an individual trip into Manhattan is a "luxury" or not can spiral deep into hypothetical territory ("OK, what if you're coming from Staten Island carrying 4,000 novelty-sized lollipops to an orphanage in Midtown and you're also an Eagle Scout, and you have to visit your blind grandmother in SoHo 30 minutes later?") That is why state lawmakers wrote the congestion-pricing bill with the explicit requirement to raise $15 billion in bonds for the MTA to improve mass transit, and the tolling scheme will need to generate at least $1 billion a year for that to happen.

"If one group is exempt that means the rest of the people paying are going to end up paying more," explained Kate Slevin, executive vice president of state programs and advocacy at the Regional Plan Association, which has long fought for congestion pricing. "You don’t want to exempt too many categories of people, because then you end up with fewer people who are paying paying a very high toll. It’s gonna be a balancing act."

Something else Adams and other proponents for carveouts should know: The law creating congestion pricing already has an exemption and a discount. The exemption applies to "qualifying vehicle[s] transporting a person with disabilities," and residents of the central business district in Manhattan, where the tolls will be assessed, will receive tax credits for the tolls, providing they earn less than $60,000 a year.

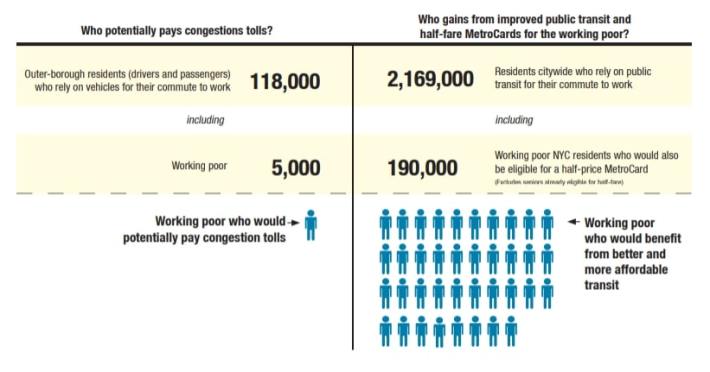

As for the myth that there are a significant number of people who are poor but also wealthy enough to drive a car, and to need to drive it into Manhattan on any kind of regular basis: according to the Community Service Society, just 2 percent of the city's working poor would be affected by congestion pricing. If politicians wading into the congestion-pricing debate are truly concerned about poor New Yorkers, they would advocate for a scheme with a minimum amount of exemptions that would raise the most money for mass transit, because that is overwhelmingly how poor people get around the five boroughs.

"We don’t want this program to hurt New Yorkers, but the vast majority on New Yorkers are not driving into Manhattan for work. They work somewhere else, or they’re taking public transit," Slevin said. "The goal here should be to invest in the public transportation system, because that’s going to lead to the broadest equity benefit."

This is, of course, what Eric Adams said a few weeks ago, when New Yorkers were forced to wade into unspeakably foul sludge-water to get on a train after it rained.

This is what happens when the MTA makes bad spending decisions for decades. We need congestion pricing $ ASAP to protect stations from street flooding, elevate entrances and add green infrastructure to absorb flash storm runoff. This cannot be New York. https://t.co/F6A5K4ahQT

— Eric Adams (@ericadamsfornyc) July 8, 2021

When the debate intensifies over the next several months, will New Yorkers see mass-transit champion Eric Adams, or the Eric Adams who racks up speeding tickets and lets his staff park all over Borough Hall? Probably both. But the sooner Gov. Cuomo, the MTA, and the federal DOT get the environmental review rolling, the sooner these constructive conversations can happen, and the sooner New Yorkers can start saving tens of thousands of years and billions of dollars.