Been there, won that.

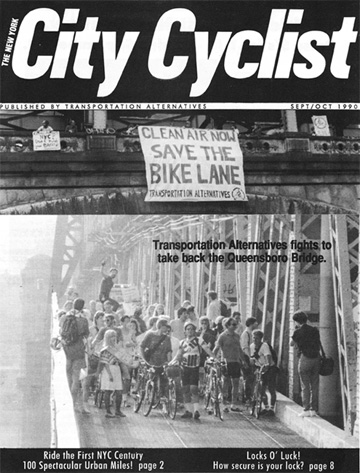

Activists will gather at the Manhattan side of the Queensboro Bridge on Sunday to demand more space for pedestrians on the fabled span, almost exactly 30 years to the day when a similar band of pedestrian advocates got arrested for seizing the south outer roadway — setting off an epic trial whose climate change implications reverberate to this day.

The protest on Sunday at 1 p.m. will tread on familiar ground: Since 2000, cyclists and pedestrians have been forced to share the very narrow and increasingly congested north outer roadway — the lone lane out of the bridge's 10 lanes reserved for anything but cars. The south outer roadway remains available only for cars, although it is closed to all users overnight because too many drivers were crashing at high speed.

The bridge's division of space is especially appalling given that cycling and walking over the bridge has been booming — with bike riding up 40 percent in just the last year. And Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer crunched the numbers last year and found that car traffic over the bridge had decreased 8.5 percent between 2006 and 2016. Meanwhile, pedestrian traffic over the bridge was up 271 percent between 2007 and 2017, when the city stopped isolating pedestrian counts, according to numbers crunched by Steven Bodzin, co-chairman of the "More Space QBB" volunteer effort at Transportation Alternatives' Western Queens volunteer committee.

"There are nine lanes for cars and one for human power," said Bodzin. "We can make it eight and two and not hurt anyone in cars."

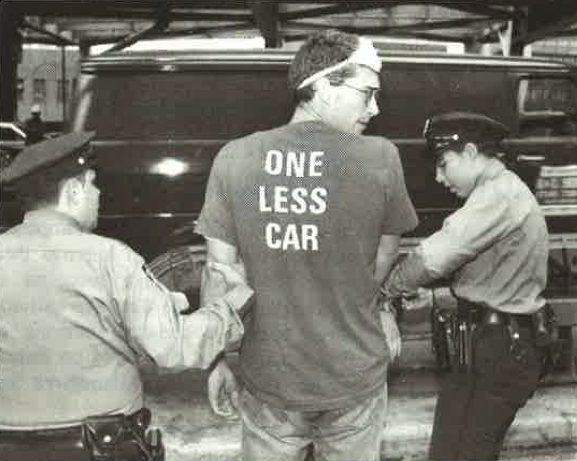

The protest will inevitably draw comparisons to a similar rally held on Oct. 22, 1990 — when six bike and pedestrian activists were arrested protesting a Dinkins Administration decision to give cars exclusive rush hour access to the south outer roadway, then the bridge's lone pedestrian path.

The arrests came after a summer of weekly protests on the span, featuring groups of pedestrians blocking cars as they walked to mid-span before turning back to Manhattan.

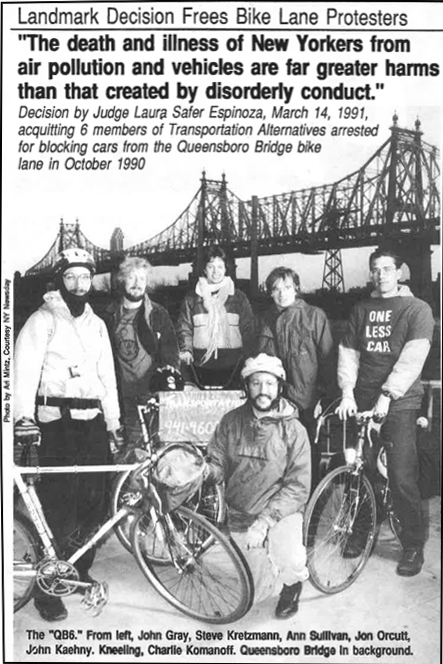

John Kaehny, an organizer of the protests and one of the so-called QB6, remembers the outrage among members of the then-less-politically powerful cycling community when their sole route to Queens was severed to accommodate cars during the evening rush.

"The South Outer Roadway is my Grand Canyon," he said this week, recalling a famous battle to prevented the national landmark from being flooded by a dam project in the 1960s. "It's a perfect symbol of the fight to change New York City from 'car first' to 'people first.' More roads lead to more cars. More bike and walking paths lead to more people biking and walking. Especially on the QBB, it really is that simple."

Kaehny, then a newcomer to New York when he was arrested, referenced the Glen Canyon dam project because of its similarity to the fight he was waging for his newly adopted hometown.

"The environmentalists failed to stop the Glen Canyon dam, but did stop [other] dams from being built," he said. "Back in 1990, when I was leading weekly, sometimes daily, marches on the Queensboro Bridge, the national enviromental movement had very little interest in livable streets and urban issues. 'My Grand Canyon' was a little speech I'd give about how what we were doing on the Queensboro Bridge South Outer Roadway was as important as stopping the destruction of the Grand Canyon because if we couldn't make cities places for walking and cycling, they would be unlivable. And without livable cities, you cannot save nature or the Earth."

As Charles Komanoff, another one of the so-called QB6, recollected it in Streetsblog a few years ago, word of Kaehny’s exuberant oratory spread, and the weekly bridge actions became a happening — and crowds swelled to 50 or 60 people. Drivers on First Avenue saw the messages "Clean Air Now" and "Just One Lane" hanging on huge sheets made earlier at Bloomberg Administration official Jon Orcutt’s Lower East Side loft (Orcutt would later be arrested, too, along with future TransAlt board president Ann Sullivan, activist Steve Kretzmann and commuter John Gray).

The Oct. 22, 1990 rally was meant to be the last, Komanoff said. "We'd made our point and it was getting cold," he said. Nonetheless, the NYPD showed up en masse and arrested the six protesters, charging them with disorderly conduct.

But rather than pleading out, they took their case to court — and won. After a two-day trial, Judge Laura Safer-Espinoza ruled that the QB6 were justified in blocking the bridge to make a larger point about air pollution (what we called global warming in the days of "the greenhouse effect").

Safer-Espinoza said that having cars in bike lanes represented a "grave harm occurring every day" so the QB6 was justified in breaking a lesser law — disorderly conduct — to fight the greater harm.

Ironically, then DOT Commissioner Ross Sandler had testified that giving cars access to the lane during rush hour reduced pollution — an argument that has been debunked via the theory of induced demand. Under cross-examination, Sandler conceded that 40 years of adding auto lanes to Manhattan had only compounded gridlock and pollution.

"Sandler's argument was fatuous," Komanoff recalled this week. "He was saying that providing an additional lane for cars would improve traffic flow and reduce pollution. But that case collapses on its own weight. And if you want more irony, Sandler signed that letter calling for construction of the LGA AirTrain — still saying that taking away a lane from the Queens Midtown Tunnel [for buses] would back up traffic and exascerbate gridlock and increase CO2. To this day, he's still ignoring the upstream benefits of discouraging car trips.

"It's deja-vu all over again," Komanoff added, referencing one of the city's greatest protectors of home.

But for Bodzin and today's activists, the issue isn't even truly "environmental" in a pollution or climate change sense.

"There's been an increase in biking and walking over that bridge and a declining failing level of service for cyclists and pedestrian," he said. "We are failing people and discouraging people from walking or biking. We all have a basic fundamental human right to space to walk around our city. But for whatever reason, we're giving all the space to a smaller number of people who have bought these big machines for themselves. So, yes, there are other superficial arguments like air pollution and traffic and congestion, but this is a basic issue of logistics: human-powered traffic on that bridge is soaring.

"The fact that the south outer roadway is closed overnight is proof of how easy it would be to turn it back into a sidewalk," Bodzin added.

He also said he did not believe there would be arrests as there were 30 years ago.

"This is an upbeat family friendly march," he said.

But Orcutt said he is more than willing to get collared under the right circumstances.

"Back then, the rallying cry was, 'Just One Lane,'" he recalled. "And now we have the numbers to say, 'One More Lane.' The bridge is not safe today with the numbers of cyclists, scooter riders, one-wheel riders and pedestrians we're seeing. This is about setting the agenda for the next leaders. And there will be electeds there."

DOT declined to comment for this story. The agency has long said it needs the south outer roadway until repairs to upper level roadways are finished in 2022. It is unclear what will happen then.

"Take the Bridge" rally, Sunday, Sept. 27, 1 p.m. Meet at the park on E. 59th St. between First and Second avenues.

To see the conditions for yourself, watch last year's Streetfilms post:

?