Did I say "break the car culture"? I meant to say "enable the car culture."

Council Speaker Corey Johnson came under friendly fire on Monday after his office revealed that it favors two recommendations for repairing the crumbling Brooklyn-Queens Expressway — both of which would cost billions and neither of which would challenge the existing domination of the car.

The Speaker's office was quick to say that Johnson was not formally endorsing either scheme — an $11-billion tunnel under Brooklyn Heights or an at-grade, $3.2-billion highway in roughly the existing location, albeit covered with a park. But Johnson did say in a statement that his frustration with "delays and half-baked plans" encouraged him to hire the engineering firm Arup to "determine the best way to spend billions of dollars to rebuild this vital roadway."

He later told Streetsblog that his goal was to spark a "conversation" about what needs to be done to not choke regional transportation while trying to open up communities that were victimized by the original sin of the highway's car-loving builder, Robert Moses.

"We need a nuanced conversation, and this report presents all the challenges and the options," said Johnson, adding that he looks forward to a day when there is no longer a need for the BQE — because transit has been dramatically improved and the freight industry has been reformed entirely.

“But I don’t think anyone right now, even the think tank gurus, have been able to figure out a way to just tear the highway down," he said.

The two recommendations were first reported by the New York Times, which received the Council's report hours before it was released to the public.

Critics — many of whom have lauded Johnson's frequently stated goal of breaking the car culture — dislike both recommendations, seeing them as non-starters (or, in the parlance of a good tabloid wood, "COJO'S BQE IS DOA").

Comptroller Scott Stringer has his own vision for a scaled-down, bus- and truck-only roadway. As such, he dismissed the Council's two alternatives.

“We have a generational opportunity to reimagine the BQE and our citywide highway network, but we need a forward-looking vision to seize this moment," Stringer told Streetsblog. "We shouldn’t spend billions of dollars doubling down on car infrastructure—instead we should plan for and invest in the sustainable future New Yorkers deserve. That means investing more in public transit, centering communities and connecting people long divided by highways like the BQE.”

Stringer and Johnson are already jockeying for position in the 2021 mayoral race, so it's inevitable that they would clash fairly regularly from here on out, but Johnson also took fire from livable streets activists.

“A highway encased in a tunnel or a box is still a highway," said Eric McClure, executive director of StreetsPAC. "Rather than talking about spending $11 billion on a 20th-century fix, New York City’s leaders should be thinking about what we can do to render the BQE unnecessary. Eleven-billion dollars could go a long way toward developing a regional freight plan that doesn’t rely on trucks and highways, building new subway and rail lines, and creating a true Bus Rapid Transit system. We’re better off patching the BQE for the very short term while planning for a near future without it. We can’t break car culture by preserving it."

Unfortunately, preserving car culture was the exact mandate given to ARUP, the engineering firm, which was told flat out that "the highway need[s] to be replaced," according to the Council report.

In a section marked "City Council Goals," Arup was also told whatever it recommended would nee to "rebuild the BQE in a matter that meets existing and future needs while harmonizing the facility with the surrounding environment, leaving them in a better condition than before" (emphasis added).

That sounds like forward thinking, but Transportation Alternatives Executive Director Danny Harris picked it apart in an epic Twitter storm.

"We can't #RepealRobertMoses by replacing outdated car infrastructure and spending billions on new car infrastructure," he said. "We do it by removing car-based infrastructure, building better public transit and protected bike lanes, and creating space for people."

The Future of the BQE is really a conversation about the future of NYC infrastructure and the legacy of Robert Moses on this city. Millions of New Yorkers have and continue to be left behind by the racist & car-centric urban renewal of our past. We must #RepealRobertMoses.

— Danny Harris (@DannyHarris_TA) February 24, 2020

How did we get here?

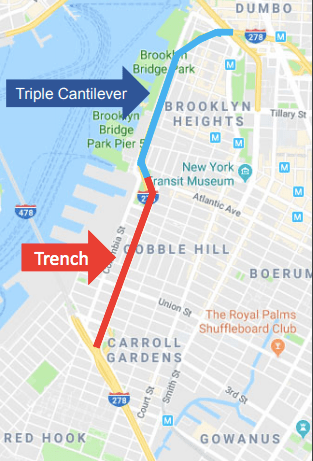

Without rehashing all the history since Robert Moses built the crumbling triple-cantilever section 70 years ago, the roadway is falling apart, in part because it's handling far more traffic — roughly 153,000 vehicles a day — and much heavier traffic than it was designed to handle. It could fall apart tomorrow or in five years, but it will fall apart.

So...

In September, 2018, the city put forth two repair options, one of which would have replaced the fabled Brooklyn Heights Promenade with a temporary highway for six years. The other option called for lane-by-lane repair that would have taken even longer. Both were so hated that...

What happens next?

On Tuesday morning, the Council's transportation committee will hold a hearing on the Council report. The Arup team will be on hand to present its recommendations, and explain why it rejected other alternatives, including tearing down the highway and not replacing it, as some, including Streetsblog, have called for.

The engineers rejected removing the triple-cantilever expressway in favor of a boulevard-style roadway, even though they admitted, "This alternative would create a more human-scaled solution in the form of a surface boulevard with facilities for pedestrians and cyclists." The problem, however, was that "it would likely be constantly congested, creating a new type of barrier."

That's why car-enablers will likely support the Bjarke Ingels highway-under-a-park plan. It's cheaper — $3.2 billion — and it hides the highway from the eyes, even though it doesn't hide it from neighbors' lungs or the planet's warming atmosphere.

The plan "has the highest rated end state outcomes, pointing to several creative solutions for a modern urban highway," the Council report states, presupposing that a "modern urban highway" is what New Yorkers need or want.

But don't count out the tunnel, which Arup estimated would cost between $5 billion and $11 billion.

"The tunnel alternative had been dismissed in the past, but should be reconsidered as it is technically feasible, is aided by better ventilation and tunneling technology, and would provide substantial benefits to a larger section of Brooklyn," the report states. "The higher cost of construction should be balanced against the larger scale of benefits."

Those benefits include the fill-in "trench" section in Carroll Gardens and Cobble Hill, plus an enhanced surface street from Hamilton Avenue to Bedford Avenue for local access.

Experts did point out that tunnel cost estimates are almost always too low — and that tunnels don't change the essential problem with cars.

"Dear NYC," tweeted former Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn. "Spend $11 billion to get ready for climate change, not $11 billion to make it worse. P.S.: a tunnel won't cost just $11 billion."

Dear NYC,

— Mike McGinn (@mayormcginn) February 24, 2020

Spend $11 billion to get ready for climate change, not $11 billion to make it worse.

P.s.,a tunnel won't cost just $11 billion. https://t.co/vkjl94oatW

It's not the first time Johnson had frustrated livable streets activists by walking back his vow to "break the car culture." At the Transportation Alternatives' Vision Zero conference last year, he suggested that he really wants to bend the car culture more than break it. And Johnson was not a full supporter of the car-free 14th Street busway, though he has since praised its success and called for more.