"This case is about the nature of a neighborhood and a community. Morris Park Avenue is currently two lanes in each direction. ... But under the plan, called the Morris Park Avenue Safety Improvement Project, it will no longer be the same community. Four lanes will go down to two lanes with a center turn lane. It's the demolition of the community."

That was lawyer John Parker's opening statement in a largely unheralded case that was finally heard Monday pitting a few business owners in the Bronx against, in short, Vision Zero.

To Parker and his clients — Coqui Sales Appliance, Window King, Morris Park Bake Shop and Captain’s Pizza — Mayor de Blasio's signature road safety initiative is not only illegal and unnecessary, but it will "destroy" the Morris Park neighborhood.

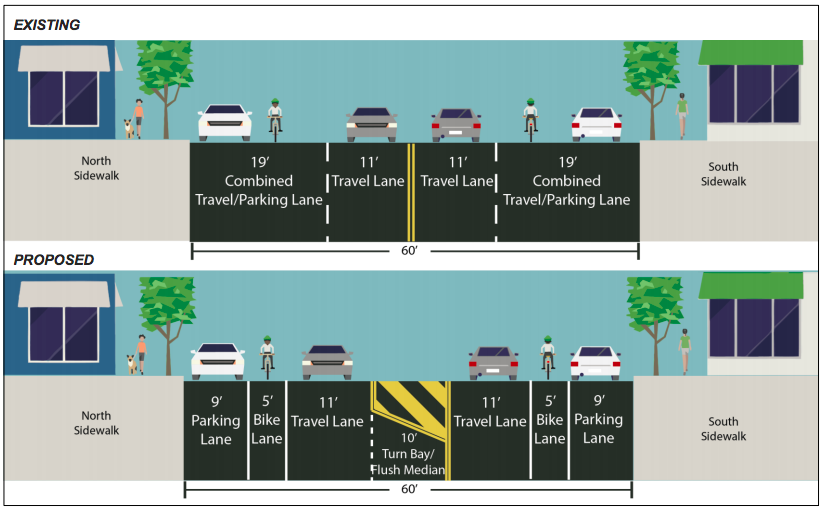

Parker's argument was enough to persuade a Bronx judge to last month block the city from undertaking its street safety redesign for the 1.5-miles stretch between Adams Street and Newport Avenue, which calls for the following "demolition" of the neighborhood: reducing two lanes of car travel in each direction to one lane of car travel in each direction, plus left-turn bays and a painted bike lane in each direction. It's a change that the city has made to dozens of roadways, none of which caused any neighborhoods to be wiped off the map.

Still, Parker and his clients have made it a legal matter — which is what brought all the participants to the courtroom of Bronx Judge Lucindo Suarez on Monday. Spoiler alert: Suarez heard the historic case with two hours of oral arguments, but did not lift the temporary restraining order. Until he rules, the city cannot redesign Morris Park Avenue to make it safe. And therein lies a story...

So what happened?

Suarez got assigned to the case only minutes before lawyers gathered in his fourth-floor courtroom — a point he repeatedly stressed. His knowledge of the specific issues of road design, some broad issues about Vision Zero and the merely advisory role of community boards was occasionally limited — but he was also keenly aware of several holes in Parker's case.

But the biggest shocker was how Suarez, whose personality can barely be contained within the four walls of a courtroom, allowed Parker to take control from the outset.

Parker is an excellent lawyer. With Suarez's tacit approval, Parker spun an opening statement that seized the narrative of the case and put city lawyers on the defensive — and tried to obfuscate the central legal issue, namely that the city simply has the power to do what it wishes on Morris Park Avenue whether a few businesses, or, indeed, all businesses, want it or not.

Parker disagreed.

"The city out of whole cloth created the Vision Zero program," Parker said, reiterating his court papers that claim Vision Zero is illegal because the de Blasio administration created it without "legislative authorization or direction" from the state or City Council.

Suarez noticed the hole in that cloth.

"Since when does any municipality need that to do improvements?" he asked.

"We’re not challenging their right to do it," he said before doing just that. "But there was no [legislative] direction on how to do this. And in this case, it destroys the community."

Suarez was unpersuaded. "If there’s no formula [created by a legislature], it does not prevent a municipality from going forward," he said.

Parker again seized the narrative. Sure, he argued, the government can go forward — but what if it's going forward for the wrong reasons? "Government," he said, "should be held to account for the actions they take based upon how they say they are going to take those actions."

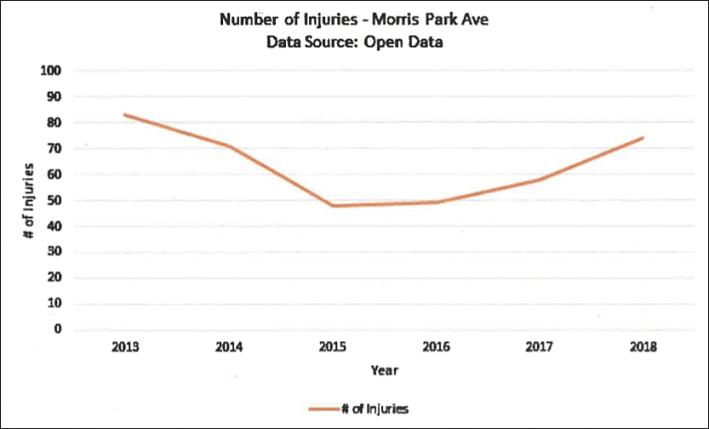

"They say this [project] is about data [but] we believe the data does not support what they’re doing," he said, citing an independent analysis done by "an expert" that showed safety is improving on Morris Park Avenue. (City lawyers later rebutted that argument by pointing out that the "expert" — whom Parker kept referring to as "Expert Russo," as if "Expert" was his legal first name — conveniently chose the bloodiest year on Morris Park Avenue as his benchmark so he could say crashes were going down.)

Is Morris Park Avenue unsafe?

One issue that kept being debated is actually something that is not debatable: No matter how you slice it, Morris Park Avenue is unsafe. Between 2010 and 2014, there were 367 total injuries (282 to car occupants, 14 to bicyclists and 71 to pedestrians), plus fatalities or severe injuries to 12 car occupants, one bicyclist and one pedestrian).

The DOT's next data set, covering 2013 to 2017 suggests that the roadway became a tiny bit more safe: There were 337 total injuries (256 to car occupants, 11 to bicyclists and 70 to pedestrians), plus fatalities or severe injuries to 10 car occupants, one bicyclist and five pedestrians.

Parker told Suarez that the drop in total injuries explains why DOT reclassified Morris Park Avenue from a "priority corridor" to a "priority location" — as if the key word was the second one and not the first one.

"The data concludes that Morris Park Avenue has improved to the point where it [was] delisted, so there’s no need for these changes," he argued.

Here, Parker is simply wrong: DOTs testimony, and city crash data, reveal that Morris Park Avenue remains a dangerous stretch of roadway. It "ranks in top third of corridors for all crashes in the Bronx during the latest five-year period," Chris Brunson, the director of safety projects and programs in the DOT's Office of Research, Implementation and Safety, testified in court papers.

Suarez could have dismissed the case right then and there — the city's only requirement is that it demonstrate that it makes its decisions on a rational basis, not in an "arbitrary and capricious" manner. The city is not bound by any statute to listen to community boards, local businesses, 1,700 signatures from mostly car owners, or even a Council member with a megaphone screaming, "Shame!" The only requirement is a rational reading of the data.

But Parker persisted. "No one in this community is saying we want to live on an unsafe roadway," he said. "The argument is we struggle and we’ve been thriving. Don’t take that away from us."

(City testimony argues the opposite — a neighborhood can't thrive if its main strip is a killing zone: After undertaking six other four-to-three road diets in the Bronx, total injuries dropped 29 percent and the number of crashes dropped by 9 percent on those roadways.)

How did city lawyers do?

The sheer force of Parker's vehemence put the city on the defense throughout, but eventually city attorneys Mark Muschenheim and Yungbi Jang punched back, with Jang taking the lead.

She opened by telling Suarez that since the temporary restraining order was put in place, there were 26 crashes on Morris Park Avenue, resulting in 11 injuries (the DOT later said there were 29 crashes between April 27 and June 7). Parker, who hadn't seen the data, expressed outrage, blaming the city for not repainting lines on Morris Park Avenue after it was milled in anticipation of the new roadway configuration.

"The blood is not on our hands or the community's hands," he said — though it was his legal argument that led to the restraining order that delayed the city's painting of lines, which currently only consist of a double-yellow divider down the middle. (And it was members of the community, after all, who got in the crashes.)

Unlike Parker, Jang made her points in muted tones, even when her argument was strongest.

"This street improvement plan is not arbitrary and capricious," she started. "When DOT looks into projects, it looks at the numbers of people who have been killed or seriously injured. [And] we also look at speeding. Morris Par Avenue remains in the top three in the Bronx for number of crashes. And 61 percent of the cars are above the speed limit, which is a 27-percent increase since 2014."

A rational basis for a street safety proposal, one could argue.

"This street improvement project is tailored for this corridor and for the safety conditions we observed: speeding, crashes and double-parking," she said. "The petitioners' notion that it is a 'cookie cutter' ... misses the point. We gave other examples [in court papers] because the conditions were similar to Morris Park Avenue. And in those neighborhoods there was a decrease in crashes. That was the point of giving those examples."

Again, sounds rational.

But if you needed an appeal to emotion, Jang provided that, too, telling Suarez that a crash on Morris Park Avenue at Van Buren Street on Aug. 19, 2018 that killed a motorcyclist.

"The DOT wanted to implement the Morris Park Avenue Safety Improvement Project in April, 2018," Jang said. "Could that death have been prevented?"

Does history have its eyes on Morris Park Avenue?

In the end, there are two ways to view the Morris Park Avenue case: it is either the legal equivalent of a pothole repair or it is a critical legal case that will determine whether city officials will ever get control of car-choked, dangerous roadways where death is just one text to a distracted driver away.

Suarez will not likely rule, as Parker wants, that Vision Zero is illegal, arbitrary or capricious. Governments have long had the power to repave or redesign roads based on its bureaucrats' reading of the data. And, thanks to a landmark court ruling in 2016, the city can be held liable for civil penalties if it does not improve the safety of a roadway after being alerted to the danger.

But community opposition has often stymied public officials from doing what they know to be right and what the law allows. And Vision Zero has not been challenged in just such a manner, a spokesman for the Law Department said.

As the hearing ended, Suarez might have been tipping his hand when he gave Parker the last word, again letting him create his own narrative.

"This is a Draconian change that will put people out of business," he said (ignoring city data that show that better designed roadways actually improve business).

Parker won the day at least. Suarez left the temporary restraining order in place until he renders a full decision.

"I have to read all this stuff and I just got it a few hours ago!" he said, using his vivaciousness as a gavel. As far as when a ruling can be expected, he added, "Today is June 10, so I would say sooner or later."