This is your bike lane on drugs.

The federal Drug Enforcement Administration's New York Office has blocked off the new protected cycle route on 10th Avenue between 16th and 17th streets, forcing bike riders and delivery workers to swerve into traffic.

The narcotic enforcement agency's New York headquarters is located at 99 10th Avenue — and that's exactly where you'll find orange construction barricades and cones placed by the agency to keep cyclists away and to allow DEA officers to park illegally against the curb.

On Tuesday, Streetsblog observed a couple of placard-bearing vehicles and one 1-800-GOT-JUNK truck parked in the blocked-off area. Same as it always is.

"Some days it’s all filled with cars. They just use that whole lane. I think it’s not even that they don’t want cyclists there. It’s that they want that parking space,” said Matt Horan, who commutes by bike along that stretch.

Horan has filed a complaint with the Department of Transportation through 311. The agency told him that the DEA uses the area for parking and "staging" and that he should contact traffic enforcement. He has, with little success.

How we got here

The 10th Avenue project was first presented to Community Board 4 in 2022, and there was no mention of the DEA block or the agency's apparent need to be exempted from a crucial street safety project.

The plan always called for a “double wide” bike lane, a beloved part of the DOT toolkit because it accommodates cyclists of all abilities and speeds without conflict.

“The future of bike lanes is here, right before us,” then-Deputy Mayor for Operations Meera Joshi said at a press conference unveiling the wider lane in 2023. “Everyone benefits from narrower car corridors, more pedestrian islands, wider pedestrian spaces, and bike lanes.”

Apparently not everyone. According to neighborhood leaders, the DEA objected shortly after the work commenced, which explains why the space for the bike lane is delineated with white street paint, but the block between 16th and 17th streets is the only one without the signature kermit green bike lane paint.

“This was a normal block and it would've been treated like any other block. That was the plan," said the board's Transportation Committee Chair Christine Berthet, who was present at the initial presentation. "I cannot explain what happened except [later] the DEA raised issue with the bike lane, as if it was increasing danger, which it’s not.”

Berthet's account suggests that the DEA heard about the plan, but the agency claimed it was not informed by the DOT.

"Unfortunately, DEA New York was neither contacted nor consulted when the city attempted to designate a bike lane directly in front of an extremely active garage used daily by hundreds of Special Agents, Task Force Officers, and employees," Frank Tarentino, the special agent in charge of the New York office, told Streetsblog.

It is not clear that the city agency has a responsibility to inform every property owner of every street painting project that could affect a single tenant. But a DOT spokesperson disputed the DEA's. account, saying the agency did contact the building owner to discuss and tweak the project before installation.

Apparently, the proposed tweak still did not satisfy the building's tenant, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration.

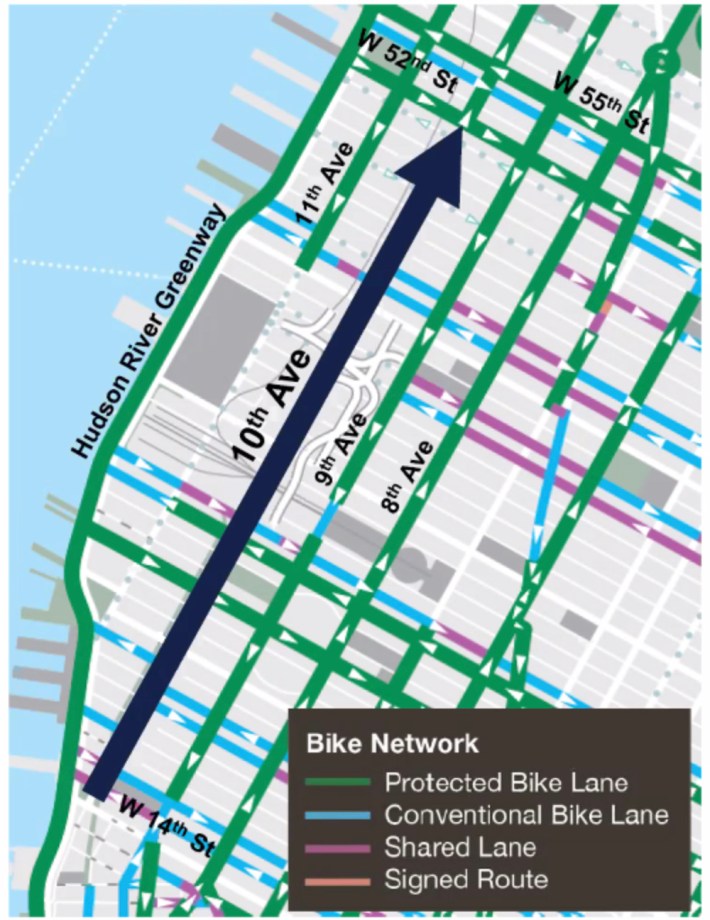

Besides that one pilfered block, the wide 10th Avenue bike lane goes from 14th Street to 53rd Street. The DEA blockade threatens the safety gains and creates a hole in the network.

"I have had a couple of harrowing mornings when cars are pulling in and out of that lot, I never know if they’re going to see me or if they’re going to stop," said Horan. "It’s so nice past there: you get this double-wide bike lane all the way uptown. It’s just incredible and then this one little section."

The DEA claims it needs the area to always be clear in the event of an emergency, though the agency did not respond to follow-up questions about what constitutes an emergency for an enforcement arm of the federal government that does not respond to 911 calls.

"As a law enforcement agency of this size, emergencies arise frequently, requiring swift and unobstructed access," was all Tarentino would say.

Berthet isn't buying what the drug agency is selling.

"I don’t understand the logic unless they are really protecting that space for possible parking,” she said. "They just want to claim their specificity and their exception."

The Department of Transportation declined to comment on the DEA's DIY redesign.

Here's what it looks like on the street: