A Brooklyn Council member wants delivery app companies to be more human and less robot.

That’s the basis of Justin Brannan's new bill, Intro 1332, which would require companies like Instacart, Grubhub, and DoorDash, and UberEats to give workers a reason for locking them out of the apps or deactivating their accounts.

“Lockouts” – or when app companies restrict workers from signing on and making deliveries at certain times – and “deactivations,” when an app company kicks off a worker entirely, have been two of the biggest complaints delivery workers have had since the minimum pay standard went into effect for restaurant delivery apps in 2023.

Brannan said he wants to get rid of the “zero sum robot boss” algorithm to make sure workers “know exactly what the criteria is that might result in deactivation.”

Upon the adoption of the city's minimum pay law last year, app companies began blocking access at certain times and deactivating accounts for reasons that were unclear, affected workers said. This not only caused confusion, but it created a backlash among some workers, who blamed the minimum pay law for the new reality.

“The worker experience of this algorithmic management is like this invisible robot boss who you can't talk to,” Brannan told Streetsblog. “A big consequence that we saw is that delivery workers are often deactivated from the platforms without any notice or any explanation.”

The app companies' algorithms prioritize workers who speed or accept many deliveries, so protecting the workers from termination is a move towards safety, advocates say.

“The city needs to enact a 'just cause' protection so delivery workers can prioritize safety without fear of retaliation,” said Ligia Guallpa, the executive director of Worker’s Justice Project, which includes Los Deliveristas Unidos, the group that fought for the pay standard.

Brannan’s bill would bar app companies from deactivating a worker (after a probation period of 30 days) without “just cause” or a “bona-fide economic reason.”

Simply put, the companies can only fire or lockout workers if there is a reason, and that reason has to be shared with workers and there has to be some other type of disciplinary action prior to deactivation.

The bill also defines “deactivation” as “any indefinite or permanent discharge, termination or layoff of an app-based delivery worker or any revocation or restriction of an app-based delivery worker’s access to the delivery platform or authorization to accept deliveries on the delivery platform.”

This way, the bill covers both instances of “deactivation” and times where workers are “locked out” but are still able to work at other days or times.

Problems with minimum pay

The bill's potential to hinder the app companies' ability to arbitrarily or transparently restrict access to the platform could be instrumental in mitigating the issues workers have had with the pay standard – mainly that there is an opaque rules system that decides when they can and can’t work.

“When we passed minimum pay the whole intention was to ensure that workers can get dignified pay, and can prioritize safety in the streets rather than trying to do as many deliveries as possible,” said Guallpa. “But the companies retaliated. They adjusted the algorithm ... so workers would still feel the pressure to do as many deliveries in less time. The companies don't want to lose any income, so their priority is how can we pay less for workers doing more.”

When the minimum pay standard was passed, it gave the companies two options for how to comply. In the “standard option,” which is what most companies use, the app's payment to each individual worker must be at or about the minimum pay rate multiplied by the sum of that worker’s trip time (time between pickup and delivery) during the week. In addition, the app’s total payment to all workers operating during that pay period must meet or exceed the minimum wage multiplied by the sum of all workers’ total time worked that week.

The second option is known as the “alternative option,” in this scenario the company pays each worker the “alternative minimum pay rate” for just the time between pickup and delivery. The alternative rate is calculated by dividing the minimum pay rate by 60 percent, which is meant to adjust the rate to include the estimated time a worker is not actively making a delivery, but is still working, known as the “utilization rate.”

Brannan’s bill would stop the companies from exploiting the loophole in the “standard method,” where their bottom line is helped by periodically locking workers out of the apps. And one economist who consulted with the city on the minimum pay law, said the alternative rate would be better for workers.

“[The standard method] is really confusing for the workers, because they don't know which basis they're being paid on,” said James Parrott, the director of economic and fiscal policies at the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School. “The companies have been manipulating that; they've created a loophole, and workers are being punished as a result of that.”

But at least one app company sees this as a false choice.

“The alternative method is a false choice since 60 percent is artificially low,” said Josh Gold, a spokesperson for Uber. “We said every company would use the standard option once they achieved 61 percent utilization — which all did. No major player uses the false choice, and I doubt any small player would either.”

A spokesperson for Wonder Group – which now owns Grubhub, Relay, and Seamless – told Streetsblog that the company is committed to pay transparency.

“We have been working closely with driver advocates and the City Council to make sure New York’s delivery workforce is protected without sacrificing the flexibility customers expect. As the bills move forward, we’ll continue working alongside them to make sure the rules are clear, workable, and squarely focused on the people powering New York’s delivery economy,” the spokesperson said.

No companies said if they support Brannan’s bill.

A wave of reform

The bill was introduced this week just after the Council passed a sweeping package of bills that would further expand labor protections for delivery workers in the city.

Grocery delivery apps like Instacart will now be forced to pay minimum wage, the app companies will have to give customers the option to tip their driver at checkout, and the companies will need to break down for workers exactly how their pay is being calculated.

These bills are now on the mayor’s desk for signature, and do face a veto. A City Hall spokesperson told Streetsblog that the mayor is “reviewing the legislation.”

Parrott said a veto would undermine Adams's attempt to be seen as a friend of working-class New Yorkers.

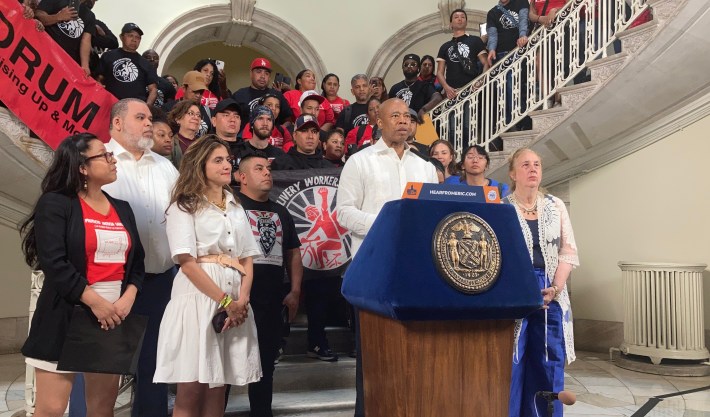

“[The mayor] was there when the minimum pay standard for the delivery workers was put in place. He's been at press conferences whenever there's been an increase in the pay. If he vetoes these bills, he’s tainting that legacy quite a bit,” said Parrott.

Instacart fought hard against the bill to expand minimum pay, and is expected to sue the city if the bill becomes law, the business website Crain’s reported.

It is unclear if Brannan's bill will face the same pushback, but the Council member said he'd rather discuss the matter in a board room rather than a courtroom.

“I don't have much sympathy for billion-dollar companies. I don't think we're asking very much of them, but I'm always open to sitting down with these companies to try to address their concerns,” said Brannan. “But it's not our job to increase their bottom line. It's our job to make sure that the people that are making them rich are treated fairly.”

Brannan said the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection would enforce the rules, like it does for the pay standard. But, he added, the next Council, and the next mayor, will have to figure all of that out — including whether to take up Mayor Adams's Department of Sustainable Delivery.

“The Mayor's Office of Sustainable Delivery honestly feels like a re-election year ploy – headline heavy but detail deficient.” Brannan said. “But I think there has to be an asterisk next to this that the next council will have to hash this out with the new administration if they decide to keep it.”