Who's gaslighting whom?

Millions of New Yorkers ride the subway every day without incident. Yet the launch of congestion pricing unleashed a torrent of new attacks that exploit real concerns about crime and homelessness on the system to unfairly portray transit as uniquely unsafe. Many of these subway detractors have ulterior political motives: they are angered to be charged $9 to drive into the most congested part of the city and are playing what MTA Chairman Janno Lieber recently called "grievance politics."

The main player has been whoever has been making the editorial decisions at the New York Post, whose exhaustive coverage of congestion pricing can be encapsulated by this story, which ran on the same day the new toll launched: "Man Stabbed in NYC Subway Station as Congestion Pricing Kicks In, Forcing More Commuters into Dangerous System."

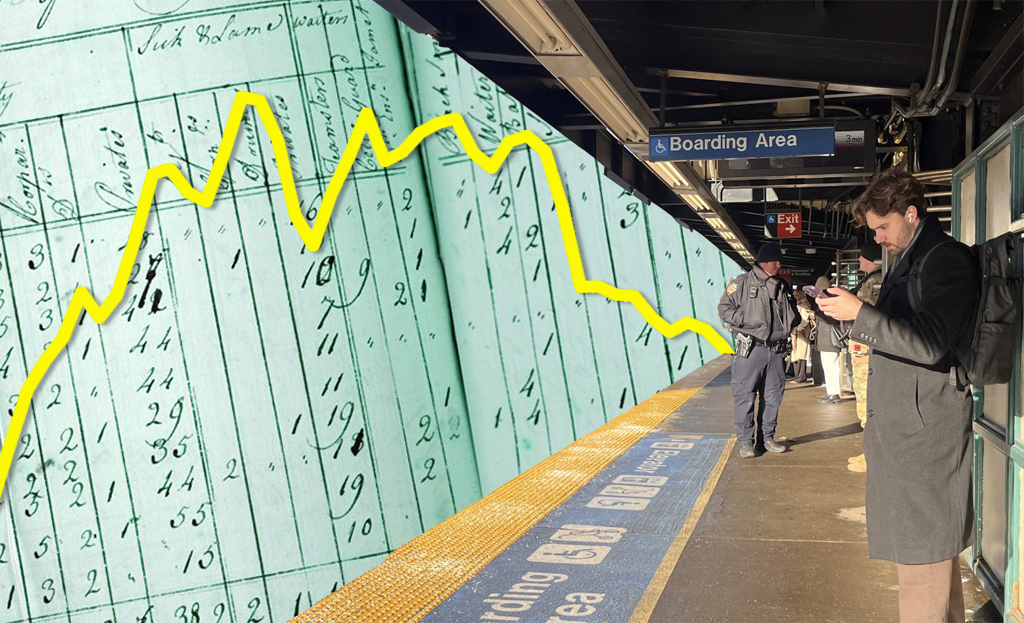

First, the facts. Crime is down in the subway from last year, but it remains up in key ways compared to before the pandemic: There were 10 murders on the subway last year, up from five the year before, which itself was a recent outlier. But last year's high homicide number did not approach the number of homicides in the "bad old days," when between 1977 and 1982 there was an average of 15 subway homicides per year, according to a 1985 MTA report retrieved from the city archives.

Felony assaults were flat last year compared to the year before: 573 vs. 572. Those numbers are higher than since the pre-pandemic period. For instance, in 2019 there were 326 recorded felony assaults in the subway. Felony assaults are up citywide compared to before the pandemic, but it's the subway crime that gets the most media attention. And the 573 felony assaults last year are still low compared to the early 1980s; in 1982, there were 903 felony assaults in the subway.

And total crime in the subway is down year over year: In 2024, there were 2,203 recorded incidents, compared to 2,337 in 2023 and 2,353 in 2022, according to the NYPD.

Two things can be true at the same time: Subway crime on the whole is rare and low, but increases in murders and felony assaults since pre-pandemic years, where New Yorkers got accustomed to very low crime numbers, is causing fear. At the same time, visible homelessness and severe mental illness coupled with several high-profile crimes have amplified those fears.

The MTA's Spring 2024 customer survey found that only 47 percent of subway riders were satisfied with the experience. But "crime" was not the main complaint; the majority of respondents cited homelessness and "unpleasant smells" as reasons for their dissatisfaction.

The pandemic created a well-documented tear in the very fabric of our society, undermining the order that New Yorkers have come to expect within the subway system. But that "order" is itself a malleable construct.

“New Yorkers have enjoyed nearly a decade, or almost two decades, of remarkably low crime,” said Richard Aborn, the president of the Citizens Crime Commission. “You now have multiple generations that have grown up in New York that have not thought all that much about crime [on the subway].

“When you see a lot of what are called ‘disorder crimes’ – graffiti, public urination, noise, homelessness, begging, filth on the subway – that is very unsettling for people, even if they don't like to say it,” added Aborn. “They're feeling it, and the manifestation of that is this fear of crime in the subway system.”

Data suggest that the homeless population, at least, the same as it ever was: An annual census conducted each winter found around 2,000 New Yorkers living in the subway system — roughy the same number as in 2019, before the pandemic. New Yorkers may feel that there are more people sleeping on the train in the post-Covid era, but the data out there shows that's not necessarily true.

What is increasing is general disorder: Calls to 911 reporting disorderly conduct or the presence of an emotionally disturbed person have doubled. There were 29,000 dispatches made by police for disorderly conduct in transit or to call for an ambulance to respond to a mental health emergency in transit in the first nine months of 2024 compared to 14,903 in the same period of 2018.

Dominating the conversation

City leaders contribute to public perceptions of danger by sending mixed messages about the situation underground: Mayor Adams and Police Commissioner Jessica Tisch point to crime's downward trend, but respond to the ongoing fear that some riders have by promising to flood the system with more cops.

This signals to New Yorkers that something is wrong — while putting the root causes of chaos on the back burner, according to civil liberties advocates.

“Despite the reality, [the mayor and the NYPD] are feeding a perception that the subways are still unsafe and they're reflexively just adding more and more officers to the subway, which just feeds into this perception that there is something wrong,” said Michael Sisitzky, assistant policy director for the New York Civil Liberties Union.

He added that the mayor's "own rhetoric ... is a real core part of this problem.”

And lest we forget, subway crime was front page news and fodder for political campaigns — including that of the mayor — long before congestion pricing was a thing; tying the two together may win political points, but it has so far failed to substantially address the issues underground.

One day they're telling me it won't work because not enough people will change their behavior.

— Andy Boenau (@Boenau) January 13, 2025

Another day they're telling me it won't work because too many people will change their behavior. https://t.co/AKoIOzMhEx

Solving those issues is expensive — last week for instance, Mayor Adams cited pledged $650 million for more homeless services, and Comptroller Brad Lander has his own plan for subway homelessness that he revealed on Monday.

Such efforts are long overdue, and it's hard to imagine generating much political enthusiasm from drivers who are already outraged to have to pay a simple $9 toll to benefit public transit.

Transportation advocates certainly aren't surprised that anti-transit, pro-car exploit subway crime — and the fear it summons — to sow discontent about congestion pricing.

"They complain about subway violence but don’t really support any real solutions to fix it, just like they complain about congestion but oppose the very thing that’s proven to reduce it," said Sara Lind, co-executive director of Open Plans, which advocated for congestion pricing. "It’s obviously not about actually fixing these problems, it’s about performing grievance and outrage."

"Unfortunately, we have decision-makers who hear the baseless outrage and act accordingly," she added.

Other risks take a back seat

Given the 1.2 billion subway rides last year, and the 2,200-plus crimes, it's arguably far safer to be underground than above ground. Last year, for example, 120 pedestrians died in car crashes and another 9,532 were injured merely walking in the city, according to data compiled by NYC Crash Mapper.

Even drivers — the people who are supposedly being "forced" into a "dangerous" subway system by congestion pricing — are unsafe above ground in New York City. Last year, 114 drivers and occupants died, and 37,257 were injured, in crashes, according to city stats. That amounts to 102 people in cars injured every single day in 2024. By comparison, there were roughly 1.6 violent crimes per day in the entire subway system.

"If you think subways are unsafe, wait until you hear about cars," added Lind of Open Plans, which shares a parent organization with Streetsblog. "Hundreds more people each year are hurt or injured by cars than in subway incidents. Traffic violence makes our streets and sidewalks very unsafe but because cars have landed on their side of the cultural battleground, that harm is just absorbed into life as the price we all pay so they can drive everywhere they choose."

Yet road violence and other dangers don't inspire the same fear or response from media and politicians as subway crime. But that's what happens: People don't respond to the actual thing that frightens them; they respond to their desire not to feel fear, said Kristen Ulmer, who wrote The Art of Fear, a book that examines how fear rules people’s lives.

“People are always looking to position their lives to feel safe,” Ulmer said. "If you look at the statistics, it’s not safe to even be alive. It’s not safe to leave your house. Life is a very precarious situation."

The uneven emphasis on subway crime in particular goes back decades, said Danny Pearlstein, director of Policy and Communications at Riders Alliance.

“It’s a very very famous and high-profile public space. So in the news, obviously if it bleeds it leads, but especially on the subway,” he said.

The ire this time

But what about congestion pricing? Why are opponents of the toll and their political allies fear-mongering to fight against a program that will increase funding for the MTA and make the city’s transit system, with almost four million daily riders, work better for those who rely on it?

They laugh at your concerns because they don't care.

— Councilwoman Vickie Paladino (@VickieforNYC) January 6, 2025

Nothing changes because they don't care.

And now this moron is going to get billions more dollars on the backs of working people to pad his completely dysfunctional and unaccountable agency -- and openly celebrate it. https://t.co/NfYHe2PgfY

For one thing, it's an easy win for politicians who haven't come up with long-term solutions to intractable problems such as homelessness and mental illness — which are much more visible to subway riders than they are to, say, drivers speeding past the problem. Narratives of disorder provide fodder for transit opponents, who don't offer solutions or blanch at the cost.

“Politicians will always exploit things,” said Aborn. "What they should be doing is arming themselves with the facts, developing some concrete solutions, coming to the legislative table and pressing for those. Exploiting [fear] for ulterior purposes is just another form of chaos."

With Gov. Hochul and Mayor Adams seeking to not discuss congestion pricing at all, it has fallen to Lieber, the MTA chairman, to respond to questions about subway crime — even if policing mass transit is technically the mayor's job.

Janno Lieber joined @errollouis tonight on "Inside City Hall" to talk about congestion pricing and address riders’ concerns over safety in the subway system. pic.twitter.com/gfOLx05z0E

— Inside City Hall (@InsideCityHall) January 8, 2025

When asked about crime last week, Lieber said, that the "high-profile incidents — you know, terrible attacks — have gotten in people’s heads and made the whole system feel unsafe."

For this, he was pilloried across the media for "gaslighting" New Yorkers.

Perhaps that's true about crime — no one can tell anyone else what that person should and should not fear; it's a personal thing — but using subway crime to argue that congestion pricing is unfair is itself misguided. Instead, congestion pricing, which is meant to incentivize taking transit, should light a fire under city and state leaders to improve the subway experience instead of serving as a cudgel for drivers to attack a toll they don't want to pay.

"It’s critical that New Yorkers both are safe and feel safe while riding the subway. At the same time, we can’t allow pro-congestion trolls to exploit and twist New Yorkers’ fears into bad-faith arguments against effectively reducing traffic and supporting and funding the very transit the city relies on," said Ben Furnas, the executive director of Transportation Alternatives. "New Yorkers ride transit, and New Yorkers need that transit to be funded, accessible, and reliable — all things that congestion pricing could turn from a hope into a reality. Miles of gridlock help no one."

And let's not forget the riders that have always been on the subway: the majority of working-class New York commuters. None of them has been quoted in any of the Post's voluminous congestion pricing coverage.

“If people are saying congestion pricing should not exist because of crime in the subway. What does that say to the millions of people that [already] ride the subway everyday and have no choice?” asked Aborn.

Let's ask them

Subway riders know what is going on.

Marshall, who works for the city and didn’t want to provide his last time, grew up in New York and has been taking the subway regularly for his entire life, even when crime was rampant in the 1970s and '80s.

“In the '70s there was a lack of public investment and you saw it in the system, violence was very prevalent at the time,” he said.

Now, 50 years later, sitting on a downtown R train from 14th Street/Union Square, Marshall told Streetsblog that social media brings everyone’s attention to incidents that may have only affected a few people in the past. The visibility of the housing crisis underground is unsettling, he said.

“There have been improvements [since the '70s], but one thing I’ve seen that concerns me is homelessness. The city is trying to provide services, but it’s not enough,” he said, adding that he doesn't feel unsafe, but is distressed at the lack of resources to help those struggling.

Rachel Sanchez, who has been riding the subway alone since she was a teen, said things feel different because of some high-profile attacks, but said she won't stop taking the train.

On a Queens-bound Q train from Herald Square, she told Streetsblog that subway crime is top of mind for New Yorkers because you can’t escape it. When things happen, you’re trapped.

“We’re stuck here, there’s no control,” she said. “Social media also plays into it, you see more crazy things online because people record them.”

— with Nolan Hicks