They're trying to make an ass out of you and me.

MTA leadership said it will assume it can ride out the $15-billion capital budget hole caused by Gridlock Gov. Kathy Hochul's congestion pricing pause — even as the agency admits that that assumption will cost $340 million every year starting next year.

The agency presented an updated financial plan to the MTA Board on Wednesday morning, and previously told reporters that the MTA is simply going to trust Gov. Hochul to provide the funding it needs in a timely fashion so that the agency doesn't have to take on the very debt about which it has warned repeatedly.

"This [plan] doesn't include any changes in debt service due to the pause in congestion pricing," MTA Chief Financial Officer Kevin Willens told reporters late on Tuesday. "One of the risks of the pause in congestion pricing is us having to issue more debt earlier, payable out of the operating budget. That has not been incorporated into the plan yet because we're taking the governor at her word that either congestion pricing will be unpaused, or replacement revenues will be found that don't require us to issue our debt earlier."

It's a clearly contradictory statement, as the MTA's guiding principle in the July financial update is to commit itself to assuming that Gov. Hochul will simply fix everything soon, though the agency could not explain why it is so confident.

"As [MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber] said, we're taking the governor at her word, so we will," said MTA Chief of External Communications John McCarthy.

The MTA was willing to be clear-eyed about the fact that lower-than-expected subway and bus revenue could cost it $811 million through 2027, and that a dip in real estate taxes means $790 million less than was expected in that same time. The agency said that those shortfalls, which are dimes compared to the loss of $15 billion from congestion pricing, would be mostly responsible for a deficit that will rise to $469 million by 2028.

But a chart illustrating the agency's revenue and expenditures from 2024 to 2027 is missing a big red line indicting the impact of the congestion pricing pause: at least $800 million in deficits caused by things like deferring capital work, missing a ridership boost from people switching to transit and paying higher debt service.

But I am always here to help you understand things, and to help the MTA communicate its needs. So I made my own version of the cumulative deficit chart to show that the MTA is going to lose at a minimum $800 million between 2025 and 2027 from not doing congestion pricing pic.twitter.com/SWm3Ix8JbX

— Good Idea Dave (@DaveCoIon) July 31, 2024

It's an explicit wishcasting scenario, agency leadership said.

"We're not really checking the timing of all these risks coming true," said Willens. "Our working assumption is we're going to get by next spring — either replacement revenues or congestion pricing is restarted. Anything we put together that tried to show the exact timing to these risks would be speculative based on what we know."

Trying to separate "risks" from "projected deficits" and "annual forecasted changes" over the next five years left budget experts agog, which several showing up at the public session on Wednesday to berate the agency for its irresponsibility.

“If the MTA issues debt earlier than anticipated, which we believe it will, it would need to pay down the debt service from the operating budget," said Lisa Daglian, the executive director of the agency's Permanent Citizens Advisory Commission. "The effect on operating funding, which pays for labor, fuels and other resources needed to maintain the service riders count on, could lead to service cuts, layoffs and drastic fare increases.”

Rachael Fauss, the senior policy adviser for Reinvent Albany, mentioned that prior fiscal plans showed a "zeroing out" of future budget deficits. And now, well, they don't.

“The MTA may politically have faith that the Governor will make them whole, but everyday riders and New Yorkers need more than I.O.U.s and half-baked promises that are no substitute for congestion pricing,” she said.

Speaker after speaker spoke of Gov. Hochul "gaslighting" New Yorkers into thinking it will all work out when the governor finds tiny bits of revenue found in the state's couch cushions — like her announcement on Tuesday that she had found the cash to fund 0.7 percent of the $7.7-billion Second Avenue subway expansion.

Without congestion pricing, the agency is going to lose out on more than just badly needed capital work that's already on the chopping block. There will be recurring hits to MTA's finances and two different one-time nine-figure costs.

Keeping older buses running is projected to cost up to $150 million per year, maintaining out-of-date commuter rail locomotives will cost $20 million per year and deferred state-of-good-repair work will cost $90 million per year. The agency is also projecting that it will take a $70 million per year hit from missing out on increased ridership in response to congestion pricing, and will lose $10 million per year thanks to reduced bus efficiency in lower Manhattan.

The MTA will pay $300 million more in borrowing costs in 2027 if it has to issue its own bonds earlier than it planned to to pay for work in the 2020-2024 plan, which MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber suggested could happen back in June. And in 2025 and 2026, the agency will lose out on up to $200 million when it needs to shift employees from the capital program to its operating side.

The new, trusting tone from the MTA stands in stark contrast to the grave tones Lieber took just over a month ago when he said that canceling congestion pricing would hurt riders in more than just delays and broken equipment, but also in service cuts and higher-than-expected fare hikes.

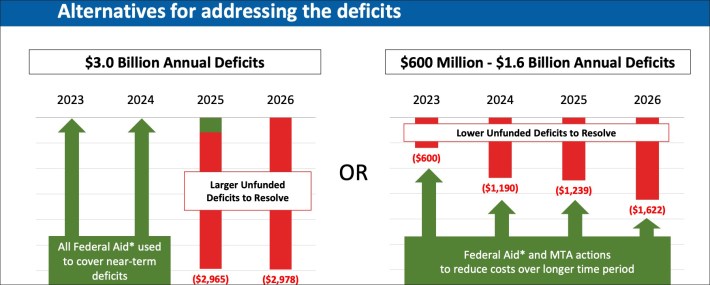

When the MTA wants to make a point about the need for Albany to shore up its finances, the agency isn’t shy. In 2022, facing multiyear deficits, the MTA showed lawmakers and the governor what its finances looked like in two possible realities: One, a fallen world where a state rescue package didn’t come through, and the other a bright and chipper world where the MTA did get the state to cover five years of deficits.

None of the presentations said anything about just assuming money would come in:

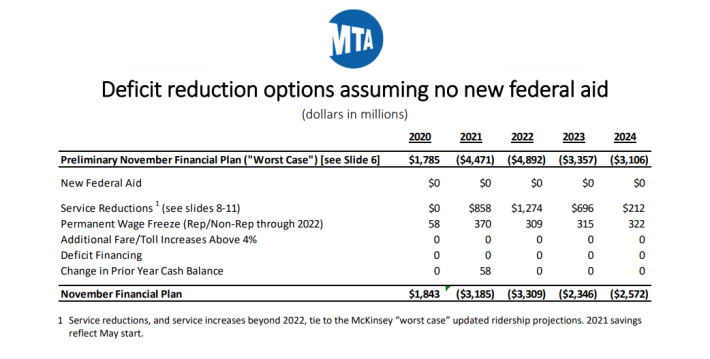

The MTA's dire warnings about its financial outlook in the face of government inaction in 2020 didn't assume anyone was coming to the rescue either. The five-year budget plan in November 2020 specifically assumed no help was coming and agency leadership laid out a doomsday scenario that included 40-percent service cuts.

There's an obvious danger in the assumption, which is that the money doesn't actually come through. From the minute the congestion pricing pause was announced, there has simply been a lack of serious proposals to fill the capital hole.

"I’m optimistic that the decision makers in Albany — all of them — understand the need and that they will respond. We can’t let the system slide back to where it was in the 1970s or even back to 2017, the summer of hell," Lieber told board members on Wednesday. “When the last capital program was under discussion, the then-governor said that congestion pricing was the alternative to a 30-percent fare hike. The operating budget will bear the brunt if we don’t get the support we need.”

And as the MTA itself spotlit two days ago, the governor is going to have to take the lead on backfilling the current capital plan and identifying real funding sources to help pay for a plan that the MTA suggested should come in at $16 billion per year to really make a difference. Nothing that's happened in the past eight weeks inspires confidence that Hochul will find a solution to either issue.

Hochul herself has said that a plan won't even be up for public discussion until next January's budget march begins, which means that if congestion pricing isn't turned on the MTA could be waiting for its cash as late as May or June.

But Willens admitted the MTA wasn't even interested in communicating what the consequences would be if the governor fumbled yet again next year — ending, for now, a mini-rebellion by MTA leadership that was previously willing to demonstrate that the fiscal and morale impact of the congestion pricing pause was the governor's fault.

"With a massive 2025-2029 capital plan shaping up to be around $70 billion, the state budget negotiations next year are going to be intense enough trying to fund the state's obligations to the transit system," Fauss said in a separate interview. "By punting on the true deficits caused by congestion pricing, the governor may try to shift blame to the Legislature if they reject half-baked proposals like we saw this June that are no real substitute for congestion pricing. The riders can't let her off the hook, and neither should the MTA."