The MTA's aging infrastructure needs a huge cash infusion just as Gov. Hochul threatens to pull the rug out from under mass transit.

The MTA needs money for new rail cars, power stations, and physical structures for elevated tracks, subway tunnels, and rail yards, officials said Monday — on top of the $15 billion threatened by the gridlock governor's "indefinite delay" of congestion pricing.

That infrastructure work is slated to be included in the MTA's as-yet-unfunded 2025-29 capital program, adding to the laundry list of unfunded needs in the current plan — which were going to be paid for by congestion pricing before Hochul stepped in.

The governor's decision to "delay" congestion pricing has called into question $15 billion of the current $55-billion capital plan's funding. If the tolls don't happen, state leaders will have to call on funding sources like tax and fare hikes to pay for the next capital plan's needs, which MTA President of Construction and Development Jamie Torres-Springer identified as essential at Monday's MTA board Capital Program Committee meeting.

"Rail cars, we don't have a choice here," Torres-Springer told board members. "We need to achieve 100 percent state-of-good-repair, that's based on useful life, how long an asset can go without being replaced. We have a lot more cars coming due in the next five years that then we've had in the last five years."

Torres-Springer's presentation hammered on the same themes that the agency emphasized in its 20-Year Needs Assessment last year, namely that equipment that is at or well past its useful life span needs to be replaced. The MTA still runs thousands of subway cars from the mid-1980s, for instance — an untenable situation that threatens basic service.

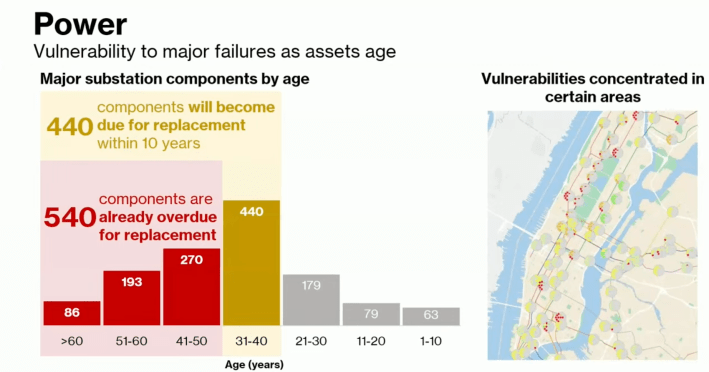

The MTA's top construction official also pointed to the need to replace major components in power substations as the kind of fix that could prevent multiple repeats of the recent subway meltdown when a transformer near Essex Street malfunctioned and disrupted multiple subway lines. The authority has almost one thousand pieces of equipment in that category that the agency says either needs replacement right now or within 10 years, he said.

Hanging over the entire proceeding was the fact that the MTA is currently $15 billion short on its 2020-24 capital plan because of Hochul congestion pricing kibosh. Torres-Springer said that the MTA is planning for the next capital plan under the assumption that the same governor who yanked away billions on a whim will soon find a new way to give the agency $15 billion.

"As we look at the 2025-2029 plan, the assumption is that the projects funded by congestion pricing are moving forward, as the governor has said. And we take her at her word — the $15 billion will be restored," said Torres-Springer.

Since canceling congestion pricing at the start of June, Hochul has yet to identify a way to fill the hole that she herself created. Recently, State Sen. Jeremy Cooney, the chair of the Senate Transportation Committee told Hochul to essentially put up or shut up, and challenged the governor to either find a new revenue stream or institute congestion pricing within 100 days.

The governor continued to insist that everything was not thrown into chaos.

"Governor Hochul has stated repeatedly that she is committed to funding the MTA Capital Plan and is working with partners in government on funding mechanisms while congestion pricing is paused," said Hochul spokesman John Lindsay.

MTA Board members know the pressure they were under — caught between the straggling current plan and an upcoming plan expected to cost tens of billions of dollars.

Instead of figuring out new revenue streams over the summer, however, the MTA has had to triage the current plan as it plans for the futrure.

"We don't know how long the pause will be," said Suffolk County representative Marc Herbst. "My guess is I don't think anything's going to until probably the passage of the next state budget to figure out if it's going to be funded at the same level. So we're not going to have a clear picture until after April of what the funding stream will be to fill this problem.

"With the unknown progress, how do we know what we can fund, and how are you going to put that before a board where we can make a decision based on our financial fiduciary responsibilities?" he added.

MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber said that the point of the July presentation was to get "major stakeholders" — hint, hint Albany — to start thinking about how to work the problem out on their side.

"What we're trying to do is to get the major stakeholders, and you know who they are, to start to think directly what what size of capital program they are prepared to support," Lieber said.

As for how much those stakeholders should be prepared to fund, Lieber himself has gone on record as saying that due to inflation alone, the next capital plan will cost more than the current record-setting $55 billion.

MTA Chief Financial Officer Kevin Willens laid some more groundwork for a large price tag for the next capital plan as well on Monday.

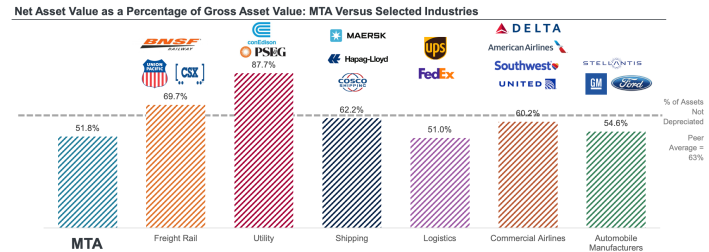

Willens, a former Wall Streeter, shared a report by JP Morgan that found that the MTA spends less in relation to the total value of its assets than companies in industries like freight rail, logistics and commercial aviation — and that the assets are significantly more degraded than the physical assets the private sector companies own.

That means that if the MTA wanted to keep up with its private sector cousins, it would take $16 billion per year to match the percentage of spending to asset value, Wilens said. But it would take even more money to catch up on the years of depreciated value the MTA's assets have suffered due to under-funding.

"We found that MTA had a fairly large depreciation gap," Wilens told board members. "More of our assets were depreciated relative to this cohort. And so what JP Morgan said is if you tried to both fund the 16 billion annually, plus make up that depreciation gap, to get rid of the backlog over a 20-year period similar to what the needs assessment laid out, that would require another $7 billion of annual investment per year over over the 20 years. So it's $16 billion as a base and $7 billion to catch up — for $23 billion a year."

The most money ever given to a capital plan has been $11 billion per year.

Transit advocates called on the governor to begin congestion pricing and stop the generational shortchanging of public transit.

"Proper care and maintenance of public transit requires more investment than New York leaders have been willing to spend, making hard choices inevitable regardless," said Riders Alliance Policy and Communications Director Danny Pearlstein.

"Gov. Hochul must start congestion pricing now to rebuild trust with stakeholders and turn the MTA around."