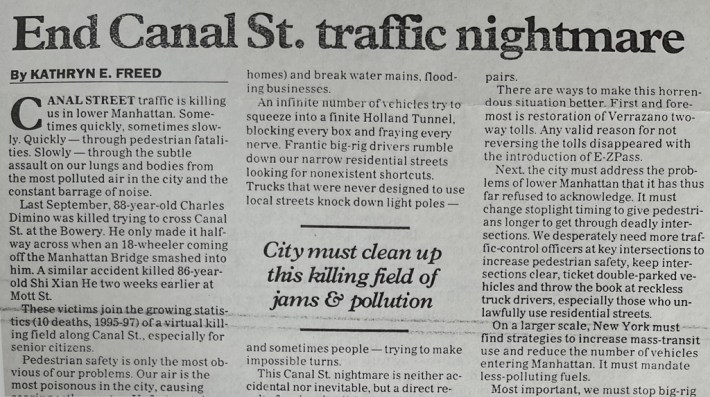

Once upon a time, Kathryn Freed, my City Council member before she made judge, railed against downtown’s “traffic nightmare.” Here’s what she wrote in a December 1998 Daily News guest essay, “End Canal St. traffic nightmare”:

Canal Street traffic is killing us in lower Manhattan. Sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly. Quickly — through pedestrian fatalities. Slowly — through the subtle assault on our lungs and bodies from the most polluted air in the city and the constant barrage of noise.

Strong stuff. Not just Canal Street but the entirety of lower Manhattan was, in Freed’s telling, a “killing field” of traffic violence, car exhaust, and big rigs. “New York must find strategies,” she demanded, “to increase mass-transit use and reduce the number of vehicles entering Manhattan.”

"Must find." Her words.

Fast-forward 25 years. Today, thanks to steadfast state officials and their citizen partners pursuing the vision of Nobel economist William Vickrey, the stage is set to increase mass-transit use and reduce the number of vehicles entering Manhattan, just as Freed wished. The MTA’s congestion pricing program, a half-century in the making, has been validated in London, Stockholm and other cities. It stands ready to banish Freed’s “killing fields” and also pay for her improved transit.

Yet Freed, a retired New York State Supreme Court justice, is suing to derail it.

Indeed, she was the main character in a New York Times story last week about last-ditch litigation to prevent congestion tolling from commencing as planned on Sunday, June 30.

According to the story, Freed “supports the concept of congestion pricing.” She even says she wrote a congestion pricing bill in the 1990s. But, she says, it will bring worsened air. “We don’t want the pollution, and I don’t think we should have to have it,” she told the Times. “Come up with a better plan.”

Ah, yes, the forever-elusive "better" plan — the magical scheme that will exempt anyone who shouldn’t have to pay and also make the handful of pollution “hot spots” go somewhere else.

Freed’s lawsuit shows that her outspokenness about traffic nightmares was just virtue-signaling. Her obstructionism links her to infamous NIMBYs like RFK Jr. (remember Cape Wind?), Dorothy Rabinowitz (remember Begrimed?), not to mention the legions of home-owners who oppose multi-family housing on grounds of “neighborhood character” even as they decry housing unaffordability and homelessness.

And the kicker: Freed and Co’s panic over poorer air quality from congestion pricing on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where she lives, is completely overblown.

I’m grateful that as a Council member Freed helped force the state Department of Motor Vehicles to provide case records on a thousand fatal pedestrian crashes in the 1990s, making possible the revolutionary data analysis in Right Of Way’s 1999 report Killed By Automobile (pdf, see p. 62). Her failure today to seek input from even a single safe streets activist before suing to block congestion pricing is hard to excuse.

In her lawsuit, Freed seized upon language in the MTA’s Environmental Assessment identifying the FDR Drive between East 10th Street and the Brooklyn Bridge as highway segments (others are the westbound I-95 approach to the George Washington Bridge and the westbound Long Island Expressway near the Queens-Midtown Tunnel) that, with congestion pricing, could experience “adverse effects on traffic conditions.”

She doesn’t mention that when the MTA analyzed the air impacts on the FDR, it found “no adverse impact” (EA, Section 17.6.1.3, p. 17-30), in part because trucks, the worst vehicular polluters by far, aren’t permitted on the highway, which eliminates truck particulate pollution as an impact on Freed, who lives close by the FDR. If that isn’t proof enough, consider that (1) the MTA minimized the possibility of traffic impacts by choosing low crossing credits and few exemptions or discounts (EA, Section 17.6.1.1, p. 17-24); and (2) the MTA’s model low-balled the number of current car trips that will “disappear,” causing it to overstate traffic impacts, as I pointed out recently.

I reached out to traffic guru “Gridlock” Sam Schwartz about the idea that not tolling drivers who stay on the FDR ― Freed’s key objection, and a requirement of the 2019 enabling legislation ― will worsen traffic on the highway. Here's what Schwartz wrote back:

Very few through-drivers currently take streets, say First or Second avenues, for the entire distance because they’re much slower. Would some drivers stay on the FDR who might have gotten off, to avoid a back-up? Yes. For example: there’s an afternoon queue on the FDR southbound to the Brooklyn Bridge; currently, some drivers may hop off at Grand Street or Montgomery (South Street) to reach an East River bridge. The $15 charge will lead them to stay on the FDR. However, they will be offset by the reduction from current traffic getting onto the southbound FDR between 60th St. and the Brooklyn Bridge or the Battery. (emphasis added)

And even in the unlikely event Sam’s forecast is off, any net increase in FDR traffic will be swamped at the macro level as the congestion toll diminishes auto traffic on the Lower East Side as a whole.

Freed’s worries about congestion pricing pollution are almost certainly unfounded, in other words. They’re insanely parochial as well. You have to be pretty self-concerned to put at risk an actual, ready-to-go, once-in-a-lifetime way to deliver the very things you once demanded — less traffic and healthier streets — simply because your own block might (might) be made worse off.

So you see, William (Vickrey), it was really nothing. Or, as the Smiths song concludes, “I don't dream about anyone except myself.” Too true for too many drivers, and too true now for Freed.