Tomorrow in Lower Manhattan, the MTA board will formally and finally approve congestion pricing. The board will likely be slammed by the stragglers who will never accept the hard truths about the societal cost of their driving, including the ineluctable reality that each minute a car is driven in the congestion zone slows other drivers by a very costly two minutes total.

Regardless of outside criticism, board members should hold their heads high when they approve the toll plan — not just because of the cool $15 billion the authority will be able to devote to transit modernization (as Times editorial writer Mara Gay just reminded us), but also because the plan will reduce congestion more than they even know.

Yes, folks, the traffic modeling that informed the MTA’s sprawling 2022 Environmental Assessment was too conservative. Here’s how I know this: buried in those 46 volumes was a modeling flaw that caused the EA to understate how many trips will be eliminated and to overstate how many trips will be diverted from the central business district. In doing so, the MTA inadvertently handed opponents ammo to blast a plan that will actually lessen, not worsen, traffic in their neighborhoods.

How do traffic models gauge the extent to which tolls will cut down on driving trips? Typically, they compute how much the toll will increase the cost to drive and run it through a “price-elasticity coefficient” inferred from examining past toll hikes. This approach underlies both MTA’s model and my Balanced Transportation Analyzer spreadsheet that state budget officials used in 2017-18 to scope congestion pricing for the 2019 authorizing legislation.

Scores of assumptions figure into the projected increase in commuters’ costs, including the toll amount and the price of gasoline. None carries the weight of the cost to park a car at its destination in the Manhattan tolling zone — below 60th Street.

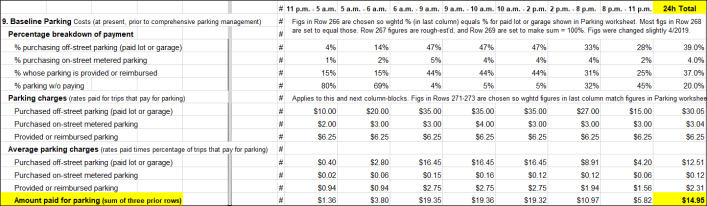

And that is where the MTA modelers tripped up. Perhaps bending over backwards to be conservative, they assumed that half of drivers into the zone pay $40 a day to park and half pay $20 — for an average of $30.

In reality, however, at least half of drivers to the Central Business District pay little or nothing to park. My detailed cost breakdown, which takes into account parking placards, employer-paid parking, placard abuse, and hosts of interstitial free spots that dot the CBD, yields an average $15 daily car parking cost in the zone — half the MTA’s assumption.

And here’s why that matters: overstating what CBD-bound drivers now pay to park powerfully diminishes the predicted number of drivers who will be dissuaded from driving by the congestion toll.

Look at it this way: A $15 toll on top of a $15 parking charge (my estimate) and, say, $5 for gas, raises the cost of a car commute by a hefty 75 percent — a steep enough rise to give lots of drivers pause.

But that same $15 toll on top of the MTA’s assumed $30 for parking (plus $5 for gas) raises the commuter’s cost by only around 40 percent. That lesser hit from the MTA’s $30 parking assumption muzzles the bite from the toll, leading the MTA’s model to understate how many car trips will disappear.

Disappeared trips are central to congestion pricing’s regional success. I estimate that the MTA’s mis-specification of parking costs caused it to undercount disappeared trips to the zone by 10,000 a day: 50,000 instead of 60,000. With that many fewer disappeared trips, the gain in CBD travel speeds gets lowballed as well, to just 9.0 percent instead of the true 10.6 percent — a difference of 15 percent.

And, most relevant to Staten Islanders freaking out over supposedly worsened traffic, these undercounts are, mathematically, the source of the unnerving prospect that lots of trips that now pass through Manhattan will detour through the Rock.

Oblivious to this, and clutching the wheel, opponents are now weaponizing the specter of traffic diversion against congestion pricing seemingly everywhere: on the Lower East Side, in Tribeca (see final two paragraphs), and in Staten Island, where Borough President Vito Fossella has made prospective pollution from diverted trips the linchpin of his campaign to stop congestion tolling altogether. Every other day, it seems, some new complainant pipes up.

Last week, the Staten Island branch of the NAACP joined the fray. “[Congestion pricing] is going to block and clog so much traffic, and this is going to impact our communities negatively,” said Jasmine Robinson, acting president. At the same March 22 presser, Fossella warned that “if the MTA’s congestion pricing program is implemented, more will get sick, more Staten Islanders will die from the increases in the resulting hazardous air pollution.”

Yet the idea that congestion pricing will cause traffic volumes to rise in places like Staten Island (or, for that matter, the South Bronx), worsening air pollution, ignores three key points:

- Trip reductions from congestion pricing will almost certainly outweigh any traffic increase in purported “hot spots” — or would if the MTA hadn’t undercounted reductions by overstating zone parking costs.

- Reduced regional vehicle miles traveled from congestion pricing will contribute to better air throughout the region by cutting down on a little-credited but significant pollution source: atmospheric conversion of nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds into deadly fine particulates (PM2.5), as air quality expert Dan Gutman and I wrote in a 2022 Streetsblog post.

- The diversions that are putting some folks on edge (or are being used to score political points) were themselves overstated because the MTA model low-balled speed gains in the congestion zone — gains that in the real world will dissuade many drivers from detouring around the CBD.

(Lest you think I’m overlooking the impact on my posited CBD speed gains from car and truck trips driving through rather than around, be assured that my calculations include these rebound effects. If they didn’t, my estimate of the MTA’s undercount of trip disappearances would be 20 percent larger.)

Are these points nitpicks? I don’t believe so. I’ll bet my hat that after a brief shakedown period, there won’t be a single spot bigger than a block in the New York region with more traffic and worse air.

Any takers?