Welcome to Streetsblog's annual "Bus Week," where we'll spend the next five days exploring why New York City buses are so horrible, what can be done about it, and what Mayor Adams is and is not doing. We open with a look at Bus Rapid Transit, a global phenomenon that New York turns into a pale facsimile in the form of short busways or the decades-old car-free Fulton Mall in Brooklyn.

Johannesburg, Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Bogotá and even Cleveland can do it, so why can’t New York?

New York City’s buses are among the slowest in the nation, and despite some efforts in recent years to improve commutes for its million-and-a-half daily riders, speeds on the essential people movers have failed to make headways.

A key redesign that has worked in other cities is bus rapid transit, or BRT, which repurposes significant amounts of street space exclusively for buses, something the city attempted to emulate with a pared-back version of BRT known as Select Bus Service.

Full BRT adds better-designed bus lanes and intersections to keep the way clear of traffic, off-board fare collections and built out stations that are level with the bus for quick boarding — a concept Adams vowed to bring to the Big Apple during his mayoral campaign, but has seemingly abandoned.

City and state leaders established SBS routes across the city, cutting through the splintered New York transportation bureaucracy, but those efforts faded into the background just before the COVID-19 outbreak.

Experts and advocates called on leaders to return to this well-established transportation design as a way of finally rolling out the world-class surface transit that the five boroughs deserve.

“In New York City, the bias against the bus tends to be because it’s slow, and not because people are afraid to ride the bus. We’re a very transit-riding city, but it’s so slow that it’s really not so appealing,” said Annie Weinstock, president of the planning firm BRT Planning International. “Each element of BRT correlates with decreased travel time. If the ride was fast, then people would use it.”

Mayor Adams ran for office in 2021 saying he would create a "State-Of-The-Art Bus Transit System," including BRT, but City Hall not released any plans like that ever since, and bus boosters are losing hope in this mayor to think big. One of the biggest projects that the city has discussed — a busway on Fordham Road — was abandoned amid minor concerns of a few business owners.

"This is a megacity, where most people who live in this city don’t own a car. We’ve got a great subway system, but we also have a great bus system," said JP Patafio, a bus driver who represents Brooklyn operators at TWU Local 100. "You bring in these components, that works, and that will attract more people to come on the bus."

More intense bus revamps are key to attracting more riders and could close gaps in the subway system without boring new tunnels, said Danny Pearlstein of the advocacy group Riders Alliance.

“It’s far faster and easier to bring in fast bus service than to build a new tunnel,” he said. “Where they don’t have existing rail and tunnels, the existing infrastructure they have is the roadway. We need to squeeze more efficiency out of our roadways.”

The push is even more crucial to getting people out of cars and into transit amid the incoming congestion charge south of 60th Street in Manhattan.

What is BRT?

The term "bus rapid transit" does not only refer to the speed of buses, but the infrastructure that is built to accommodate them.

According to a guide by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, buses should get dedicated lanes where cars are not allowed, preferably running down the center of a street so they don’t have to compete with parking and deliveries along the curb and weave in and out of traffic for stops. Drivers are also less likely to intrude on a center-running lane to turn off a road, making them more self-enforcing.

Stations should be on concrete islands alongside the center paths, replacing lanes of car traffic rather than setting up stops along the curb that take up scarce sidewalk space.

“The choice is between taking space from pedestrians and taking space from cars,” Weinstock said. “There is a lot of roadway capacity in New York, First Avenue and Second Avenue, they’re very wide, so it’s possible.”

There are some bonus upgrades like well-designed stations with plentiful seating and cover from the weather, unlike the puny shelters the New York City contracts out to build in exchange for advertising space.

"If it’s raining out, even if the bus is moving fast, you don’t really want to stand there all huddled together under a tiny shelter," Weinstock said.

For more efficient boarding, fare collection should happen at stations and not on board, so buses don’t have to wait for each straphanger to pay, and stations should be flush with the floor of the bus to allow for even quicker stopping times.

“If you put together off-board fare collection and at-level boarding, you can reduce boarding time to like under a second per passenger,” said Weinstock. “It seems like a small amount but in the aggregate you actually end up saving a lot of time.”

In New York City, concrete boarding islands are rare, and even those are not quite flush with the bus for boarding, Weinstock said.

Motorists shouldn’t be allowed to get on the bus paths at all, even to make turns or drop people off, which New York’s lanes often allow, encouraging routine incursion into the red-painted paths.

In New York City, bus lanes are chronically blocked by drivers and parked cars, especially near government buildings where parking placard abuse proliferates amid a lack of enforcement.

"Current bus lanes, like on Utica [Avenue], really it’s almost like a parking lot, because they cover the plates and there’s no enforcement," Patafio said.

American transit agencies logged big boosts in ridership when they installed BRT corridors. The HealthLine in Cleveland grew trips by nearly 60 percent and sped up trips by 34 percent, while San Francisco’s Van Ness BRT similarly increased passenger numbers by 60 percent and decreased travel times by up to 35 percent, according to news and government reports. However, the Golden State bus route took 27 years and $346 million to build, so it's not a good example of quick and cheap upgrades.

New York City is in a league of its own by sheer numbers of riders and the vastness of its network, Weinstock noted, and officials should be looking at transit systems in Mexico City with its Metrobús, or Guangzhou’s BRT in China, the latter of which carries some than 850,000 riders a day, more than several subway lines.

Mayor Adams seemed to see the light on the campaign trail when it came to BRT, writing in his transportation platform (archived online by Gotham Gazette) that the city should add the bus upgrades to better connect the outer boroughs, on thoroughfares like Third Avenue and Linden Boulevard in Brooklyn.

“We should make SBS service the baseline for bus service, and take advantage of opportunities for true BRT,” candidate Adams wrote. “BRT is cost effective, high quality, and will do the most in the shortest amount of time to build out our transit network without depending solely on New York State.”

He also vowed to add 150 miles of bus lanes in his four-year term, but Hizzoner has been far less ambitious in office, adding just a little over 4 miles of protected lanes last year — a fraction of the legally required minimum of 20 miles under the Council’s Streets Master Plan.

Riders Alliance has been tracking the progress, and reports less than seven miles of bus lanes, as we near the end of the first half of Adams's four-year term.

One of the reasons for the slow progress is the Adams administration's intervention to stop upgrades on corridors like Fordham Road.

Whatever happened to the SBS?

It takes a leader to get together the state’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which operates the city’s bus network, and the city Department of Transportation, which is responsible for congestion. Both agencies banded together during the Bloomberg and part of the de Blasio era to roll out nearly two dozen SBS routes, the closest the city has come to BRT.

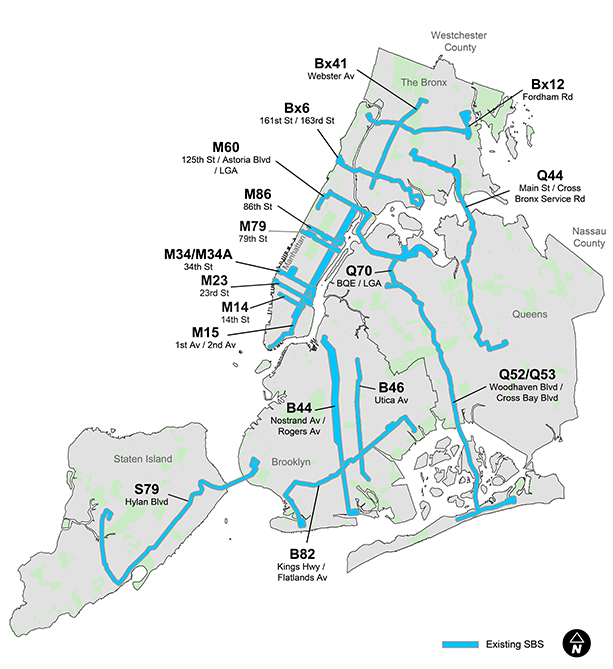

The SBS model focused on adding bus lanes, off-board fare collection, and some better boarding islands, rolling out in 2008 with the Bx12 in the Bronx, expanding to 20 lines over the following decade, the last of which arrived in 2019 on the 14th Street busway. The routes still leave many large gaps in eastern Queens, Staten Island's North Shore, and cross-town in the Bronx.

SBS achieved double-digit speed increases, more predictable commutes, and higher ridership, but it’s not a full BRT system because it still allows drivers to go onto sections of bus lanes and busways, and local buses using the same streets didn’t get the benefit of off-board fare collection.

However, SBS was an important move to make it clear that the bus was an important mode of transportation, said Jon Orcutt, who worked as a DOT policy director under the Bloomberg administration, and now leads advocacy at Bike New York.

“[The] Select Bus moniker was a way to say, buses aren’t third class,” said Jon Orcutt,

City and state transportation officials worked closely together to make that happen under then-DOT Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan and MTA Chair Lee Sander, according to Orcutt.

“It took those guys in a room to tell the rest of their agencies to cut the shit and do some projects,” he said. "New York exceptionalism is just that city government doesn’t speak with one voice on this, but a mayor that cared about it could fix that."

That included usually slow-moving agencies like the Department of Design and Construction, which is tasked with larger-scale construction projects like building out infrastructure like concrete boarding islands.

“There’s some trepidation in New York to do full BRT, because of the time it takes DDC to work,” said Pearlstein. "f you wanted to do that the way it’s done in Bogotá and other places, you would have to go to DDC."

Overcoming the split authority between the state and the city — and agencies within the city and local interest groups — is key, said Patafio, pointing to London, where the mayor controls both the buses and the street.

"Every mayor that has come before Local 100 has promised bus lanes. And then it doesn’t happen, because of the community board, so there has to be an authority to cut the Gordian Knot," the union rep said.

Switching lanes

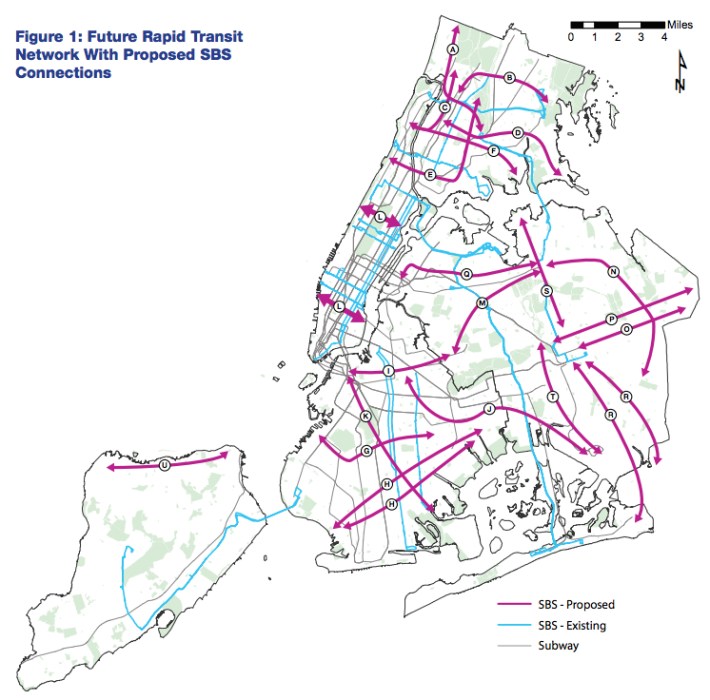

In 2017, then-Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a plan to more than double the number of SBS routes with 21 new lines, covering swaths of the city with little or no subway service, but a year later, the MTA declared a three-year moratorium on new lines citing cost-cutting measures — even though the bus expansion accounted for a small fraction of the budget trimmings.

Under the then-new New York City Transit chief Andy Byford, the agency in 2018 pivoted to its bus action plan, which focused on borough-by-borough redesigns of its ancient bus networks, allowing all-door boarding once it moved to tap-and-go OMNY fare payment, and more reliable service with a new bus command center.

Advocates started pushing more for low-hanging fruit that didn’t require a lot of money, time, and cross-agency collaboration to improve buses quickly.

The DOT could paint bus lanes and install transit signal priority much faster, which it did on a series of busways, whereby the de Blasio administration reinvented the Fulton Mall lanes by limiting through traffic, starting on 14th Street in 2019, and during the pandemic on 181st Street, Jay Street in Brooklyn, and in Flushing and Downtown Jamaica in Queens

The MTA paused its network redesigns during the pandemic, and then pushed back completion by five years until 2026, only implementing changes so far for Staten Island’s express buses, and in the Bronx. The Authority has also stalled turning on the OMNY readers it installed at the back door of every bus, because transit leaders are worried about fare evasion.

Where are we now

Following Adams’s campaign promises, there were hopeful discussions about BRT on his transition team, according to Weinstock, who sat on that crowded panel of nearly 800 people — but there has been no indications of realizing that vision since.

“There was a lot of talk about ‘we’re going to do a true BRT and we’re going to do a few corridors of true BRT,’” she said. “There was a lot of excitement around that at that point, but I haven’t heard anything about it since.”

Five years after the MTA launched its bus action plan under Byford, bus speeds remain roughly the same at just slightly above 8 miles per hour, following a peak of 9.3 MPH. at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020 when the streets were empty of traffic, according to an MTA dashboard. The SBS lines are overall faster at about 9 m.p.h on average, but have actually gotten slightly slower since 2018, the data show, dropping to 9.1 MPH from 9.5 MPH five years before. (One reason: The are simply tens of thousands more cars in the city since the pandemic, as Crain's reported.)

MTA Chair and CEO Janno Lieber famously called buses the “engines of equity,” for transporting riders that tend to be lower-income and people of color. But the borough redesigns have trickled out slower under his leadership, with only the Bronx bus redesign implemented so far, and the Authority has yet to give a clear date for when they will allow all-door boarding across the system, with Lieber dismissing its proven speed-boosting benefits as a “hypothesis.”

A final redesign plan for Queens is slated to be released “in the coming months,” and the finalized plan for Brooklyn will arrive next year, according to MTA spokesperson Kayla Shults.

“The MTA is supportive efforts to speed up buses for customers,” Shults said in a statement. “The best way to deliver faster, safer buses to customers is to move full speed ahead with our bus redesign process, which has been shown to speed up trips throughout a borough, along with increasing connections to other modes like the subway.”

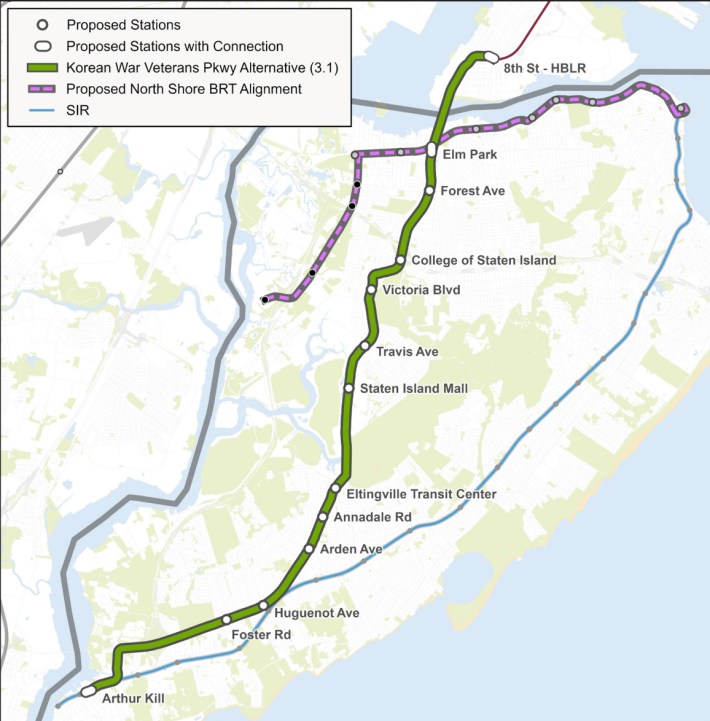

The MTA floated several BRT options in its recent 20-year needs assessment, including on Utica Avenue in Brooklyn, or on the North and West Shores of Staten Island, including a connection over the Bayonne Bridge to the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail in New Jersey.

Orcutt suggested more options, such as better routes connecting Jamaica to subway-less eastern Queens, or east-west connections in the Bronx, where the subways mostly go north-south to and from Manhattan.

Weinstock laid out proposals in a blog post last year to upgrade existing SBS routes to BRT, such as along Manhattan's East Side, while also extending buses like the B41 from Flatbush Avenue over the Manhattan Bridge to Canal Street.

DOT has implemented short projects with aspects of BRT, such as the incoming busway on the busy and placard-ridden Livingston Street corridor in Downtown Brooklyn, and center-running lanes with concrete boarding islands on Edward L. Grant Highway and Gun Hill Road in the Bronx.

And a humble one-lane bus project on the Washington Bridge is already showing promise:

Absolutely GIDDY over watching bus after bus glide right past the congestion on the newly installed buslane on #WashingtonBridge4People! 🥰 #BetterBuses Can’t wait for @NYC_DOT to start phase 2 of this project for 🚶🏾♀️🚲🧑🏻🦽 pic.twitter.com/1uKLMfSslo

— Lucia :D 飞 (@LuciaDLite) September 26, 2023

However, the agency also scaled back and then killed bus redesigns on the heavily used Fordham Road corridor in the Bronx after local politicians and businesses favored the needs of drivers, and there has been no public update since January on a plan to make an ambitiously long stretch of Flatbush Avenue better for buses.

None of the plans even come close to Adams’s campaign rhetoric of a true BRT, and advocates have little faith that the mayor, who dismissed legal benchmarks for more bus lanes in front of DOT staffers, will follow through any time soon.

“There’s a lot of scope for doing much more with buses in New York, but the city has to mean it if we’re going to do it, and I don’t think we’re going to see that under Eric Adams certainly,” said Orcutt.

Neither DOT nor City Hall responded to multiple requests for comment.