The city's failure to make life better for bus riders is worse than you knew.

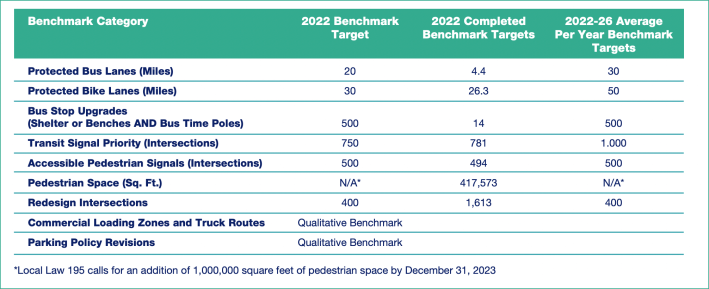

After saying last year that it would narrowly fail to meet critical benchmarks for bus lane installation, city officials admitted on Tuesday that they missed by far more than previously thought: the Department of Transportation built just 4.4 miles of protected bus lanes in 2022, less than a quarter of the 20 miles required under city law.

The dismal bus numbers are below the 11.9 miles of completed lanes DOT previously gave Streetsblog, but those stats also included unprotected stretches of red-painted road that don't count toward the mandates set by the New York City Streets Plan, according to its yearly progress update published by DOT on Valentine's Day (and two weeks late).

Worse: Straphangers waiting for buses also only got 14 out of the 500 upgrades to their stops that they were owed under the law, the report found.

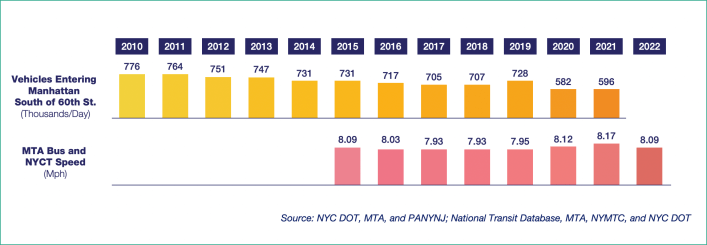

And even worse: Bus speeds declined to an average of 8.09 miles an hour in 2022 after two years of gains rising to 8.17 mph earlier in the pandemic as the streets emptied out and fewer people drove. The 2022 numbers are slightly up from pre-pandemic numbers of 7.95 mph in 2019.

The numbers mark DOT's first official review of its work on the marquee street safety legislation enacted under the last City Council in 2019, which has since suffered repeated setbacks and lacks of enforcement mechanisms to keep City Hall in check — and DOT insiders have said don't expect to hit their mandates in the coming years either.

After issuing multiple explanations for the shortcomings last year, on Tuesday, the city chalked up the setbacks to the Covid-19 pandemic along with supply chain, staffing, and contracting issues, but officials neglected to mention politicos within the Adams administration that worked to scuttle the mass transit upgrades.

Advocates again called on Hizzoner to fulfill his campaign promises to New York bus riders, who are more likely to be people of color and low income than other commuters.

"However you slice it, the Adams administration is miles wide of the mark," said Danny Pearlstein, the policy and communications director of Riders Alliance. "He’s the bus mayor. Now he’s got to govern like it."

Under the 2019 Streets Plan law DOT has to build out 150 miles of bus lanes over five years that are protected by physical barriers or stationary or mobile ticketing cameras, with at least 20 miles required in its first year of 2022.

For bikes, the city must install 250 miles of protected lanes over the same period years starting with no fewer than 30 miles in the first 12 months, but the agency fell 3.7 miles short there too, at 26.3 miles of green-painted paths the agency did last year.

The bus stop numbers were most shocking; the agency upgraded with shelters, benches and digital bus time poles fewer than 3 percent of bus stops it was required to under the city law — the lowest success rate of all benchmarks.

Officials said the failure stemmed from not having a contractor ready to install a new model of solar-powered information display poles, which they expect to get going in the middle of this year as they're supposed to add another 500 of the stop improvements.

The city's slow pace has frustrated state transit leaders with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which operates the city's buses while DOT controls the street design.

"We have to start hitting numbers," said MTA chief Janno Lieber at a recent board meeting.

Bike advocates also called into question the 26.3 miles of protected bike lanes DOT claimed to have completed last year.

A tracker by Transportation Alternatives only logged 18.9 miles so far, and one citizen inspector for the organization said he found several of the projects unfinished after the year's end.

"They are generally rideable and some even quite good, but all have more work to do," said Brandon Chamberlin, who personally checked on many of the lanes on Jan. 2. "We took the radical position that a project is only done if they have completed all the work for it. If there are still things to do, it is not done," he said.

Chamberlin listed projects that were not quite done by then, such as Kingsland Avenue in Brooklyn and Bronxdale Avenue in the Bronx that missed green paint, or 44th Drive in Queens that lacked a pedestrian island.

The agency boasted surpassing the requirements for redesigning intersections, overhauling 1,613 of the 400 required. When Adams touted some 1,300 revamped crossings last fall, about half of the junctions only got retimed traffic lights rather than full-scale overhauls.

Rodriguez — who signed onto the 2019 Streets Plan law when he was in the Council and chaired its transportation committee, but now finds himself on the other side at the helm of the $1.4-billion agency — said that their progress should not be judged just by the numbers.

"I want to stress that the effect these projects have on the lives of New Yorkers is more meaningful than a particular mileage number," Rodriguez told the Council during a transportation oversight hearing on Tuesday. "A project that is small in mileage can still improve New Yorkers' lives significantly."

The Transportation chief cited a two-block contraflow bus lane the agency recently set up outside the Pelham Bay subway station in the Bronx — a small but impactful overhaul that cut a circuitous loop and shortened commutes for straphangers commuting further into the borough.

Mayor Adams vowed to go beyond the Streets Plan on the campaign trail, by installing 150 miles of bus lanes and 300 miles in just four years, doing more in less time and pledging to give the Big Apple a "state-of-the-art bus transit system."

But DOT has been hobbled by staffing shortages depleting its upper ranks, and insiders told Streetsblog that officials with the Mayor's Office of Intergovernmental Affairs opposed to bus projects became frequent roadblocks, something City Hall later admitted in its own report card. Streetsblog also reported that the DOT doesn't think it will meet the Streets Plan numbers this year, either.