What about cabs?

When the Traffic Mobility Review Board meets this summer to set the pricing part of congestion pricing, the six-person panel will have to decide a basic policy that will be vital to the program's success: will yellow cab and Uber and Lyft drivers be subject to the congestion pricing charge? And, more important, how?

These simple questions become quite complex for one reason: The MTA's Final Environmental Assessment proposed subjecting cabs and the so-called "for hire vehicles" like Uber and Lyft to the congestion pricing toll either once per day or not at all.

That on-off switch was the result of the MTA testing multiple tolling scenarios with the goal of avoiding a disproportionately high negative effect on cab and FHV drivers, who are part of an environmental justice population.

At the same time, by law, congestion pricing needs to raise $1 billion per year, which the MTA found was possible in the seven tolling scenarios — though each comprised differing toll prices, caps, credits and exemptions for vehicles such as trucks, buses, cabs and FHVs. Those models showed that the requisite $1 billion per year could be raised with a peak-hour toll between $9 and $23.

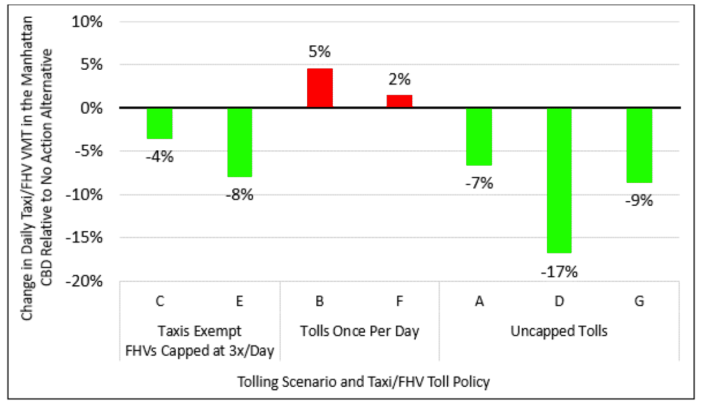

But those seven scenarios don't only predict revenue. The scenarios — including several with no cap on how many times taxis and FHVs could be tolled per day, others with a once-per-day cap and still others with no fee at all for taxis to enter the zone — projected widely different results for congestion reduction, the other stated goal of central business district tolling.

One scenario with no cap on taxi tolls (Scenario D) found that taxi trips south of 60th Street would drop as much as 16.8 percent. But a scenario with a once-per-day charge (Scenario B) would increase taxi trips by 4.6 percent.

But what's fair?

Exempting taxi and FHV drivers from paying an additional charge that could be as high as $23 is seen as a matter of fairness (why should cabbies pay when it is their passengers who are causing the congestion) and practicality (how would a cab driver pass along portions of a once-per-day toll to each of his or her passengers?).

Yellow cab drivers and FHV drivers also collect taxes and fees from passengers that go towards the MTA. Yellow cab passengers pay 50 cents on every trip that ends in the 12-county MTA service area, plus an additional $2.50 for any trip that begins, ends or passes through Manhattan south of 96th Street.

FHV passengers pay a $2.75 congestion surcharge for similar trips south of 96th Street. That congestion surcharge, implemented in 2019, was originally pitched as the first piece of congestion pricing itself and has delivered $900 million to the MTA through March 2022, the last publicly available balance from the surcharge.

After the MTA reached its mitigation agreement with the Federal Highway Administration, the agency ran the numbers again to see what a once-a-day toll or a total exemption would do for revenue projections and for cab and FHV traffic south of 60th Street.

All the rejiggered tolling scenarios predicted increases in taxi and FHV traffic between 20 and 50 percent more than the numbers in the graphic above, but only two of the proposed toll scenarios found that agency would need to make up for missing money by charging a higher toll than originally pitched:

- For Scenario A (originally a $9 peak toll for private vehicles with no caps on taxi or FHV tolling), the MTA found it would need to raise the toll by 10 to 15 percent on private vehicles and trucks if it wanted to toll taxis and FHV just once per day. The increased amount of cabs and FHVs in lower Manhattan would be balanced out with a 2- to 3-percent reduction in private vehicles and trucks in this scenario.

- Scenario G (originally a $12 peak toll for private vehicles and no cap on taxis and FHVs), the MTA would need to raise that peak toll by about 10 percent to cover revenue lost by switching to a once per day toll for taxis and FHVs. That increase would also raise the number of extra trucks passing through the Bronx from 50 per day to 251 per day, which is a separate concern regarding impacts to environmental justice communities.

Another county heard from

Despite the MTA-FHWA agreement that cabs would be tolled once or not at all, one Albany lawmaker and a longtime congestion pricing advocate have proposed a different path: having Uber and Lyft passengers pay a higher surcharge for rides in lower Manhattan than they currently do, in order to exempt for-hire vehicle drivers themselves from having to pay the upcoming traffic toll.

Assembly Member Robert Carroll (D-Park Slope) and congestion pricing advocate Alex Matthiessen used an op-ed in Crain's to propose replacing the current $2.75 surcharge on for-hire vehicle rides in Manhattan south of 96th Street with a two-tiered surcharge on those trips:

- Uber and Lyft passengers entering the zone would pay half of whatever the peak-hour toll turns out to be.

- Those passengers taking rides entirely within the congestion zone would pay slightly more than that.

The proposal entirely exempts yellow cab rides from the increased surcharge.

"We think that this will go to the passengers who are disproportionately wealthier than the average New Yorker and significantly wealthier than the driver," said Carroll. "This is for the truly luxurious trips, something like taking a cab from Tribeca to Chelsea or Midtown, where you've got multiple subway lines."

He added that it "just makes no sense" to put a once-a-day fee "on drivers" when the passengers are the ones who should pay.

However, none of the scenarios the MTA considered had a separate per-trip fee charged to the customer like Matthiessen and Carroll have proposed, nor did the mitigation effort the MTA agreed to include that policy.

It's unclear then, whether the TMRB actually has the ability to implement a fee structure like this. Carroll and Matthiessen's plan could be seen as undermining the very foundation of the environmental assessment, which could open up congestion pricing to months more review by the federal government — right when the feds are about to officially grant congestion pricing a Finding of No Significant Impact.

And despite the fact that $2.50 surcharge on taxi trips south of 96th Street and $2.75 surcharge on FHV trips south of 96th was pitched as a "first step" for congestion pricing, and Uber has been running ads claiming their customers pay congestion pricing charges, the surcharge technically exists as a separate law from the congestion program that the federal government has weighed in on.

Carroll said he believes the TMRB can recommend implementing a fee similar to the one he and Matthiessen recommended, and that it is necessary for the board to implement it given the enormous amount of taxis and FHVs in Manhattan. The city's 2019 Mobility Report found that over half of the traffic in Midtown Manhattan was comprised of cabs and FHVs, and even as traffic patterns were changed by the pandemic, Carroll and Matthiessen wrote there were more than 52 million FHV trips that began and ended south of 60th Street in 2022.

"We think the TMRB does have the authority to do this. And then if they don't, they should explicitly say to the legislature, and I'll get a bill drafted and start working to either pass it or get it done in the budget. Because it would be insane to create a congestion pricing scheme, where Uber and Lyft riders are not paying a congestion charge. The surcharge that we added did nothing to dissuade use [of FHVs]. We need a congestion charge for when people are using Uber and Lyft, and that charge should be calibrated to try to minimize 15 percent to 20 percent of Uber or Lyft trips that touch the zone just like we're trying to reduce 15 percent to 20 percent of car trips that will touch the zone," said Carroll.

A popular idea?

FHV companies themselves, who have shown tenuous support for congestion pricing, like the idea of a per-ride fee, but Josh Gold, the senior director of policy and communications for Uber, cast doubt on whether it was possible under the agreement the MTA reached with the FHWA.

"I’m sure we have a different opinion on the amount of the charge, but, yes, this is the type of per-trip [fee] we lobbied for extensively and repeatedly," said Gold. "Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like the agreement with the federal government allows for that."

Advocates for taxi and FHV drivers said they could live with the per-trip fee.

"This proposal is not that far off of how things should be," said New York Taxi Worker Alliance President Bhairavi Desai. "What I've been saying since last year is that yellow cabs as a service should be exempt [from congestion pricing], and then on the FHV, side, drivers should be exempt so that they're not paying for it."

Desai added that the per-ride fee would need to be properly calibrated so as not to depress FHV trips so much that drivers lose jobs en masse. (For now, her organization is fighting for no tolls on taxi and FHV passengers, and will rally at Gov. Hochul's office on Wednesday.)

Desai isn't alone in thinking that the price of a FHV trip doesn't have to be extremely high. Charles Komanoff, a transportation economist and longtime advocate for congestion pricing, said that the societal cost of a car trip into lower Manhattan in the form of traffic, emissions, noise and crashes, is about $100 to $200, meaning that even a $23 toll wouldn't recoup the true cost of one of those trips. Komanoff pitched charging the trips by time spent in the zone as a way to deter longer taxi and FHV trips that cause the most traffic, but said a per-ride charge was also a fair way to charge those customers a fraction of what their ride costs the rest of the city.

Even a $15 or $20 peak toll would not recoup 100 percent of the cost of congestion on drivers of private vehicles, but a fraction, says Komanoff, who has estimated that the societal cost of every trip into the congestion zone is as much as $200.

"So if we are only dinging a private car owner 10 percent to 20 percent of the societal congestion cost, then in principle, we should be doing the same with the for-hire vehicles," he said. "And if we were to do that, we wouldn't be charging them half of the congestion tolls that we are going to be charging private cars."

Komanoff added that he agreed with Desai, Carroll and Matthiessen that the yellow cab industry deserves a break after it was almost disrupted out of existence.

"Yellow cab drivers, they bought into the system, they paid into the system, and they were guaranteed an exclusive franchise to operate in the Manhattan taxi zone. And that was just ripped out of their arms a dozen years ago when Uber set up to do business here," he said.

There are other people who think yellow cabs don't deserve the carve-out. Gold said that since private equity firm Marblegate Asset Management is the largest holder of taxi medallions in the city, the argument to exempt cabs on economic fairness grounds doesn't fly. And taxi industry expert Bruce Schaller suggested that making a distinction between the two ways of getting around risks just creating yellow cab-driven congestion.

"If you tax ride-hail and not yellows, people will shift from the former to the latter," said Schaller. "That misses the point of congestion pricing. It's fine to integrate other goals into the main menu, but not if they undercut the core point of congestion pricing in the first place."