Slate's cities reporter Henry Grabar's new book, Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World (Penguin Press), could have been a sleeper, aimed at livable cities nerds who already know how drivers' obsessive demand for free car storage has ruined our cities and enabled sprawl, all the while devastating our air quality and congesting our roads. Instead, it's quickly becoming a media sensation that's catching the attention of people far outside the movement — and getting them talking about the need for reform.

Cars are an experiment that has failed everywhere: In Chicago, where a privatization-obsessed mayor undervalued parking spaces — and lost $1 billion in a deal with Wall Street. In Los Angeles, downtown merchants were so obsessed with "getting back" suburban shoppers that they turned their entire neighborhood into a shopping crater. In New York, city fathers decided that all the garbage should be stored on the sidewalk (in the way of pedestrians) rather than in the curb lane because too much parking would be "lost."

Every city has such a story. So on this episode of The Brake, guest host Gersh Kuntzman gabs with Grabar about some of the most shocking stories from America's long love affair with asphalt.

Tune in below, on Apple Podcasts, or anywhere else you listen.

This excerpt has been edited for clarity and length.

Gersh Kuntzman: There are a lot of stories about how parking policy has transformed America. Which do you think really stands out as a singular example of the parking saga as the overarching public enemy number one?

Henry Grabar: Well, if we just want to think about the arbitrage between the value of parking and the price of parking — which is what a lot of these issues come down to, right — it's that parking is something that nobody really wants to pay for. But if you think of that land as being possibly used for something else, then suddenly it becomes potentially very valuable to people.

And if you think about it, in those terms, Manhattan is in the league of its own, right? New York City has some of the most valuable land on the entire planet, and you can still park your car there for free. I think that that is kind of shocking when when you when you really think about it.

For listeners who aren't familiar with New York City, we have a very unique practice of putting our garbage in black trash bags piled high on the sidewalk. And one of the reasons we do that is because we are reluctant to take away curb parking spaces, to create space for containers where the trash can be picked up in containers. And the city just released this report saying, 'You know what, we could put the trash in containers — but it would cost us 150,000 parking spaces.' I think the consensus is that that's a nonstarter, we're not going to take away that many parking spaces.

We are literally living in filth. And when you put it in those terms, it just shows you how people think about parking, and their reluctance to to give that space up for any other use.

GK: Stick with the with the other uses for a second. It's very hard to get most drivers to even see the curb side lanes as public space — not just in New York, but in every city. I mean, sure, they see a bike lane every once in a while against the curb, and they see a bus lane every once in a while against the curb. But as you mentioned in the book, and we all obviously all experienced with the pandemic, there are a million other uses for that public space. Why is it so hard to get drivers to see the curbside lane as public space?

HG: Well, I mean, it's been 100 years since we decided to dedicate our curbs to car storage. So the idea that there could be anything else there is literally beyond the reach of human memory at this point.

You come across this moment in in American history, where we begin to dedicate the curb to car storage. But streets, as you know, weren't always just for moving cars and stored cars, right? Like, prior to the 1920s, there were all these different things that used to happen in the street; kids would play, people would sell things, it was a space to store construction materials, I mean, we had all kinds of different ideas about what to do with this public space. And we don't want to resurrect all of those, obviously — there was also a great deal of garbage in the street at that time. But I think the short answer to your question is that it is actually beyond the reach of human memory.

And so what we've begun to see over the last 20 years – with parklets in San Francisco, and most recently, obviously the Open Restaurants program in New York, and many, many other cities that have dedicated curb parking to restaurant space, planting trees and shrubs to soak up stormwater — I mean, all this stuff is just a blink of an eye in the whole history of the curb. And so it is going to take a while for people to adjust their expectations.

GK: Well, that's the frustrating thing, frankly, for people who are in the livable streets community. Because like you talked about the notion of parking being at the intersection of land use and transportation. These are very critical issues. Land use, especially though, is really critical in the book because of people's perception of parking. As you write, "the need for a perfect parking space has also shaped the country's physical landscape." You know, like if the organizing principle of American architecture. You talk about many different examples of how cities have changed. So, yes, it's outside the human memory of all the people living on the planet remembering cities, before there were cars, but you also point out in the book, for example, that when people go on vacation, they tend to choose many options in which they aren't going to be surrounded by cars. I mean, Disneyland is about most American of those examples. But all the cities in Europe where you walk around and it's so nice to walk around and you you may not even be really conscious of it. But I guess what I'm asking is, why don't why don't we realize that the thing we crave is the thing we've gotten rid of, like why is that so hard? Given all the examples you give in the book?

HG: One of the one of the people I profiled in the book is this guy, Mark Vallianatos, who leads this tour of Los Angeles that he calls the Forbidden City Tour. And so he takes you around all these like beautiful early 20th-century neighborhoods in LA, and then explains why because of the way we've designed our zoning and parking codes, they're impossible to build today. And I think that's that is really an eye-opening moment for people in part because it's so counterintuitive — we all know those are the things we like best and everyone wonders why we don't build them like we used to. And why is that? Well, I mean, it's really complicated for one thing. Every city has different codes and can't expect you know, your every, every day. Everyone has other things to think about than sifting through their their cities, parking minimums and well being out there right or wrong.

GK: I'm gonna push back on that a little bit because that's true of really all of the arcane topics of running a city transportation, sanitation, policing, etc. But like you mentioned, Don Shoup, there were certainly academics, and also architects and also developers who certainly were aware of parking, and its potentially positive effect on their business, but also the deleterious effect. For example, in the book, you talk very specifically about a bunch of different examples of developers who thought, "Oh, we gotta get these suburban shoppers. Let's build these parking." So it's not as if people weren't aware of what was going on. But they, like Robert Moses, thought, "Well, this was progress, and the automobile is going to be the thing that's going to save our businesses if we cater to the automobile."

HG: Yeah. Let me take another stab at that. Upon further reflection, I think something also deserves to be said. It's not just that these issues are complicated and require a great deal of activism from the livable streets movement; it can really take up a lot of time to show up to all these community meetings and be the person who stands up and says, "You know, what, we need this affordable housing in the neighborhood." Not to mention vitriol from from your neighbors. So there's that, but I think the other thing right when we talk about cities, it's awfully hard to look at a city and imagine it being completely different — like the ability to stand there on a street corner and shift your perspective to envision a completely different street in front of you. That's a challenging project if you have never experienced that. And so a lot of people may not realize that Amsterdam and Paris looked like American cities once to the extent that they were also full of smoggy honking traffic, right? Amsterdam wasn't always bicycle paradise. In the 1970s, it was full of cars as well. And I think part of it is helping people imagine that a better world is possible.

GK: Yeah in New York, there are people who say, "Well, we're not Amsterdam." Well, Amsterdam wasn't Amsterdam until it was Amsterdam. Now I want to shift gears. You mention community board meetings or city council meetings all across the city where the issue of parking comes up and it's always couching something else. You bring up some examples where it was clearly racially motivated that residents of a small town wouldn't want a particular housing development that wouldn't have as much parking. The book had so many examples of how the existing rules make it harder to build housing. But the thing is, these rules are often couched as an equity issue, but the irony is, of course, that the more expensive housing becomes, the more working class people are priced out of the desirable areas where they wouldn't need a car, so they need to get a car so they can get to those areas for their jobs, but yet we don't provide the transit because suddenly they all have cars — and it becomes this vicious cycle of car dependency baked into the system. And it's all about the parking, but it's really about racism and about class and about housing costs and about gentrification, all these other things. So how we even discuss these topics at those community boards or at those city councils when people like you and activists I know are called elitists or racist. They're called gentrifiers. Yet, in the end, this is an equity issue, but it's the flip side of the equity issue.

HG: It's complicated because cities have become a lot of these neighborhoods that were supposed to be destroyed in part because they were considered to have an obsolete housing stock of mixed-use buildings and rentals and high rises and all that, frankly, good stuff, have now become so in demand that they are perceived as exclusive and many of them are. And so the question is: is there something egalitarian about being able to park for free? I think there is definitely is. The idea that anybody can drive in from anywhere and park on Mulberry Street for free, you know, there is something appealing about that.

And I want to push back on two points against that argument. And the first is that free parking has many, many negative externalities, but in brief, big consequences for the environment, traffic congestion, and simply the time it takes to find a space to park, which for working people is a serious concern. Sometimes people say, well, like people who work with their cars, they need free parking. But maybe they like free parking, but a lot of them also really need to get where they're going and if you're somebody who works with your car, your time is worth money.

The second point is the relationship between parking and housing. When I was reporting the book, I talked to a land-use planning professor at the University of Texas in Austin, and we were talking to his students about whether parking on the UT campus should be paid or not. And they really didn't like that idea. And the reason they didn't like that idea was because many of them had been priced out of the neighborhood and they live 20 or even 40 minutes away from campus and they have to drive every day. So for them free parking is this really crucial symbol and reality of access to their education. And it's hard to shift the conversation. The question is not why can't you park here? It's why can't you live here? That's the question we should be asking and it does require a bit of a paradigm shift to say, "You have to understand that the paid parking is part and parcel of being able to permit big apartment buildings with no parking to be built." Because the neighbors just will not allow that if there's free parking on the street. There have to be limits. Otherwise, everybody's going to come with a car and leave it on the street all day.

GK: There are many cities that have insufficient transit. So sometimes I wonder at this point, how could we ever have a suitable transit system, given we've had 100 years of car dependence, and people sprawling out and suburban commuters are even commuting from one suburb to another not even coming coming into the downtown area anymore. So are we simply stuck? Is there any way to really turn that around at this point, because the massive investment in public transit isn't happening.

HG: Well, my long-term vision of America, since you asked ...

GK: President Grabar, go ahead.

HG: We need pretty significant population growth, more liberalized immigration policy, eventually growing cities all across the country, and that's just going to increase our incentive to use the land we have a little more intelligently. So I think suburbs can be retrofitted to become the kinds of neighborhoods that have sufficient density to not only one day support transit, but perhaps before that happens, a sufficient residential density to support walkable amenities, infrastructure, the infrastructure of civic life, schools and so forth, and all of that so you would be able to walk or bike or take a golf cart or whatever, to get to all these things.

I think there's obviously cities where we are a very long way from being able to provide safe and reliable alternatives to driving for everyone. So it's about it's about change at the margins, right? Maybe you still need that car to make the commute downtown or make the commute to the other suburb where you work, or even going to the shopping mall, but maybe we could start at like a baseline policy that kids should be able to get the school by themselves. If we were just to try and build to that standard, we would come up with much better ideas about housing density, street design, all this stuff. And again, like maybe that just takes a couple car trips off the road, but at the margins, maybe it means that a family with three cars can go down to two family. Or a family with two cars can down to one.

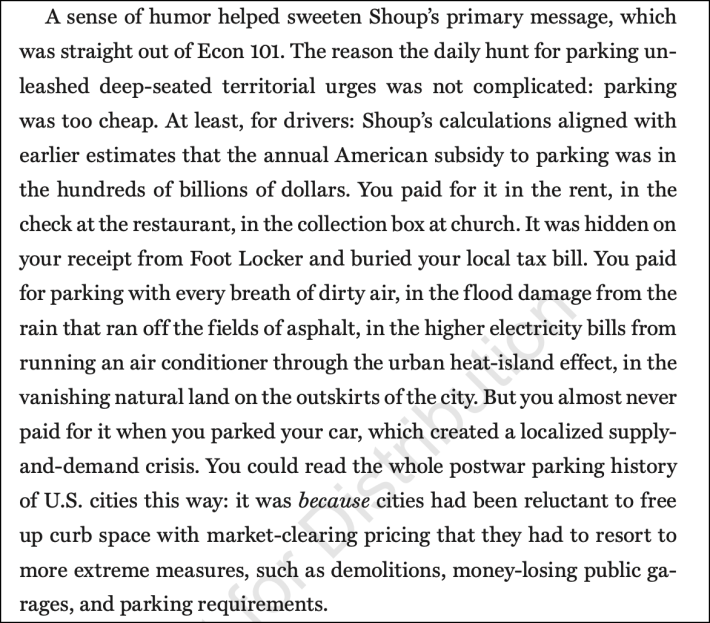

GK: But drivers don't see the terrible conditions they create. If you have the book in front of you, listeners, go to page 150 [or look at it, right] because there's a section about all the ways in which our society subsidizes car ownership and parking. And it's like a really long list, and there's another part of the book where you talk about all the externalities. And it's just amazing to me that otherwise smart people, who can see those externalities on other social problems, can't see it on cars.

HG: I think a lot of people do see these externalities. I think that when you drill down to it, a lot of people recognize that cars are bad. In fact, even 20 years ago, right during the Iraq War, I feel there was a much broader acceptance on the part of liberals in particular, only liberals, that the our automobile dependency was part of our dependence on foreign oil and definitely a mistake, something went wrong and, and we ought to try and fix it somehow. And that was sort of like part of your progressive bonafides at that time. And the politics around oil have changed since then because America is now one of the largest oil producers in the world. And so that that line of argument or like what we call it, like, driver guilt, has sort of slipped away. But I think there's lots of places where like, I see people who I don't think of as being anti-car activists who sometimes have a moment of recognition when they themselves are on foot somewhere and they say like, "Wow, we really did create a lot of problems for ourselves in this dependence on cars." That perspective shift can only occur when you're outside the car. So how do you get politicians on board with these reforms? Just put them on a bicycle. I think that just getting outside of the car for a moment, and seeing the world through the fresh eyes of not being in a vehicle is probably like the most radicalizing thing you can do.

GK: Electric cars are obviously the next big investment that America is going to make in another century of car dependence. And, again, liberal people who would know the car it has deleterious effects on their life, on the life of their neighbors, on the life of their kids, they still see the electric car as kind of, "Oh, well, it's electric." That's going to have so many ramification not just on road violence, which is not going to get better, and not just on congestion, because congestion will still be there, but the biggest problem is they're going to control the curb again, because we got to charge these things now. The way in which the car will dominate our cities and dominate our land use decision and dominate our sprawl and undermine transit is not at all going to be helped by the fact that they're electric.

HG: I couldn't agree with you more. You can be pro-electric car without making the argument like, "Hey, don't worry about the congestion. Don't worry about the air quality in your kid's classroom because the cars will be electric soon." I have not seen any of that.

GK: Well that's because that's the "Wizard of Oz" argument: "Pay no attention to that deleterious effect behind the curtain."

HG: It's a challenging question because I do think that America has baked in at least another century of dependence on the private personal automobile. And if we're going to do that, as you know, transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. So we do need to electrify the fleet. That is really important, but it also should not serve as an excuse to keep so many of our best public spaces and just so many of our priorities downgraded because we decided to put the car first.