The City Council's new permanent outdoor dining bill would require businesses to submit to reviews from politicians, preservation officials, and community boards to get licenses for outdoor dining — threatening to reverse gains of the pandemic-era program that brought the popular "street-eries" to neighborhoods that had never had them before, according restaurateurs, experts and others familiar with the city's old al fresco permit process.

Establishments like French bistro Chez Oskar in Bedford-Stuvyesant, Brooklyn, will have to go through those extra obstacles to set up seating, despite having already transformed the road and sidewalk space around them into elaborate structures for nearly three years.

"This will kill the program for many," said the restaurant's owner Charlotta Janssen. "And when the next pandemic hits, what then?"

Under the Council's latest proposal, businesses will have to apply to the city for separate licenses to have outdoor dining on the sidewalk or the roadway, and they will have to take down their roadside setups from December through March, with a deadline to remove the current sheds by November 2024.

The Department of Transportation will remain the main agency in charge, but several other arms of municipal government now get a say on the applications as well, including the City Council which can hold votes to disapprove applications.

City Council members will be allowed to hold a public hearing and vote on any restaurant's outdoor dining application if a majority of its 51 members approve a resolution to do so. Community boards, meanwhile, will get 40 days to hold a hearing for every sidewalk cafe. If a board recommends denial or modification of an outdoor seating and the restaurants disagrees, DOT would have to hold another hearing.

If a business happens to be in one of the city's 156 historic districts — such as outdoor dining-heavy neighborhoods like the West Village or Bedford-Stuyvesant — or on or adjacent to one of 37,800 landmark properties, it will have to get approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which has 11 commissioners and a staff of 80 people.

All that — on top of the fact the outdoor set-ups will have to come down in the winter — may be too much for some restaurants, including La Nacional, a 155-year-old Spanish restaurant on West 14th Street, adjacent to a landmarked building.

“For most restaurants, going through any sort of city red tape is already incredibly complicated and many will just opt not to do it," said Rob Sanfiz, La Nacional's executive director. “Wealthy restaurants will be able to pay for it, and ones that work on tiny margins like ours, we will not."

“The cost for us, it’s probably gonna mean the end of outdoor dining as we know it."

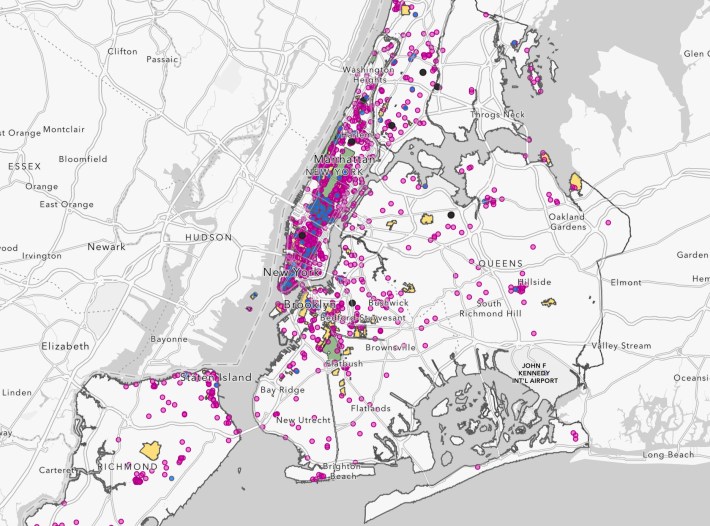

The pandemic Open Restaurants program brought outdoor dining to parts of the city that never had it before — particular blue collar neighborhoods with a majority of residents of color, a New York University study from January found.

"It was inevitable that the permanent program was going to have a little bit more regulatory steps to it — coming from an emergency program established under the pandemic," said NYU graduate student Dominic Sonkowsky, who co-authored the study.

"The current bill may go too far and there’s a good chance that the losses will be concentrated in these majority people of color neighborhoods, disproportionately low-income neighborhoods."

The added layers of bureaucracy will make it easier for opponents to derail any new outdoor dining setup, according to one Manhattan street safety advocate who has seen lengthy city review processes first hand as a member of Community Board 6.

"Every additional approval step drags out the process, and provides an opportunity for bad-faith opponents to delay an amenity that the community wants to enjoy and someone is offering to pay for," said Rich Mintz.

Of course, 6,000-pound SUVs don't require of these sign-offs to park in historic district that long preceded the advent of the automobile.

"There’s nothing exactly historic about the modern cars on streets with buildings from like the 1800s and early 1900s," said Sonkowsky, the NYU researcher.

"If the concern is preserving the historic nature of these street blocks, I think it is more historical to place outdoor dining on these street blocks than it is to place parked cars."

The pandemic-era program was allowed to circumvent many of city's usual reviews because de Blasio and then Adams authorized it through executive orders under the national Covid-19 emergency, which the federal government ended last week.

To make a permanent program, community boards and the LPC have a right to weigh in under the City Charter, according to the mayor's office.

The bill's sponsor, Council member Marjorie Velázquez, who chairs the Council's committee on consumer and worker protection, said her proposal will make it "easier and less expensive for restaurants to participate in the outdoor dining program," calling the pandemic version "not a fair comparison."

"We have removed zoning restrictions that blocked restaurants in the outer boroughs from participating, reduced the review time for application approvals, expanded licenses to last longer periods of time, and significantly decreased the participation costs for restaurants," the Bronx pol said in a statement. "As roadway structures will be movable, we don't anticipate businesses having issues taking them down."

The Council Speaker's press office did not respond to a request for comment.