Remember that cable study of the Brooklyn Bridge that the Department of Transportation has been saying since 2016 needed to be done before the city could make the bridge safer for cyclists and pedestrians?

Um, never mind.

The DOT admitted this week that the all-important, must-have, can't-do-anything-without-it cable study — announced in 2017, supposed to start in 2019, and again in 2020 — never actually started.

As a practical matter, the cable study is probably moot at this point, given that the city ended up creating a bike lane on the roadbed of bridge in 2021 — an alternative to a widened promenade that it repeatedly dismissed.

But the saga of the Brooklyn Bridge cable study remains an object lesson in instructive for how city government puts off action for years until it suddenly finds that it actually can solve a problem that allegedly needs one more study, one more round of outreach, one more season of unrelated work.

Versions of the cable-study-that-was-vitally-important-until-it-wasn't-important-at-all can be spotted all over city government: The MTA's long-delayed pilot on all-door bus boarding pilot has stalled out over hazy excuses about OMNY usage, the Addabbo Bridge between Howard Beach and the Rockaways still has a painted bike lane next to 40 mph traffic because of an endless series of reviews and finger-pointing, a proposed Fordham Road busway withers away under baseless opposition from business interests as does a similar project on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

And, of course, pedestrians and cyclists using the Queensboro Bridge, have been thrown into conflict for years on a narrow shared path because the city has always managed delay its promise to turn the south outer roadway into a pedestrian path. At one point, then-Department of Transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg said the conversion of the south outer roadway couldn't happen until the city got money to install a suicide fence. Then when the money was provided by local Council members, the new excuse — a "garbage" one, according to a current member of the Council — is that the conversion can't happen until the completion of road repairs that are, themselves, delayed.

Insiders know what to call it: intentional slow-walking.

"These are the kinds of things that can be sped up or adjudicated by agency leadership," said Bike New York Director of Advocacy Jon Orcutt, who's also a former policy director at the DOT. "The answer can't always be, 'We can't do it.' You have to find a way: tell me what the problems are and I'll work on them, whether it's outside the agency or if it's some other part of the agency all that stuff."

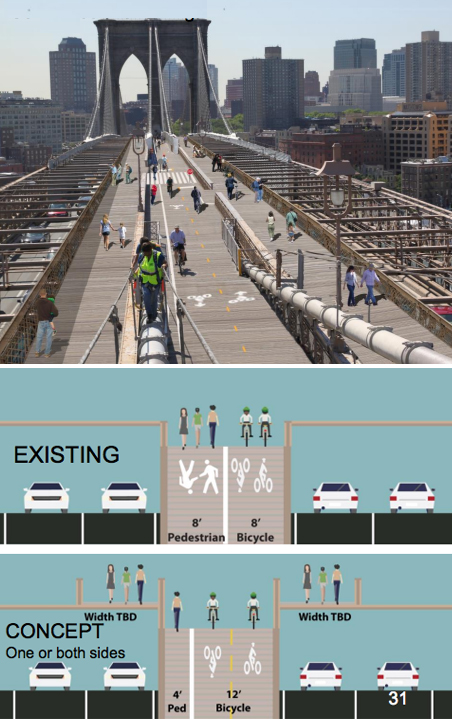

But let's not come off the the cable inspection saga just yet because it's so delightful: The story dates all the way back to 2016, when the DOT first said it was exploring widening the walkway on the Brooklyn Bridge to keep pedestrians safe from the increasing numbers of cyclists using the walkway. But that wider promenade — seen in glorious renderings (right) — was contingent on a study to determine if it was realistic to build a walkway on the steel girders over the bridge's roadbed.

A study by the engineering firm AECOM found that the bridge could support the weight of the platform, but in 2017, Trottenberg said that the city still had to study whether the bridge cables would hold up if people actually used it, which necessitated a cable inspection that was slated to start in 2019.

That bridge inspection was supposed to take two years, but by early 2020, Trottenberg said that the cable inspection still hadn't started — and that taking a lane of the roadbed for a bike lane was still off the table. But by January 2021, the city suddenly announced it had figured out how to build the bike lane that now exists.

Just as suddenly, the cable inspection was lost to the dustbin of history.

But even with cyclists enjoying their slice of asphalt, the bridge promenade is still packed with vendors and their would-be customers, and crowding can still a problem, even in the winter, such as this jam packed pedestrian situation on New Year's Day this year:

The Brooklyn Bridge is a stampede risk right now. Doesn’t seem like anyone monitors the crowds. It was scary. pic.twitter.com/J1I9UamfxZ

— Kathy Park Price (@KathyParkPrice) January 1, 2023

So perhaps that bridge cable inspection is still needed, if only to help out the pedestrians caught in the crush. But will it happen? It depends on who will push the bureaucracy — in this case, the DOT's all-powerful bridge unit. (For the record, DOT said it still plans on doing the study.)

"This all represents bureaucracies," said Orcutt. "And the way you cut through that is leadership, by just saying. 'Listen, we're doing something. We're meeting today, and next week I want you to come back and give me a plan.' It's not a democracy; the commissioner, the agency leader can just tell people what to do."

Even the National Association of City Transportation Officials — of which New York's DOT is a member — said that head-knocking support from the top is the way to push through stalled-out projects.

"Without a champion for transportation projects who can advocate upwards while mediating transportation-related disputes across agencies or divisions, projects can get stuck, be tabled, or never get prioritized to start with," the organization wrote in in its recent report, Structured for Success.